A Brief Introduction

The problem of human trafficking is now of major global concern. Immense resources, at national and international levels, are expended to research and combat human trafficking.¹ However, it was not always the case that human trafficking was considered such a priority. The story of how human trafficking gained such widespread attention is intimately tied to how human trafficking is now legally defined. To understand this connection, there are several legal doctrines to understand.

White Slavery and Anti-Vice Crusades

In the mid-19th century, the concept of “white slavery” emerged to articulate a concern for women and a disdain for sexual commerce. In both the United States and Britain, anti-vice vigilance groups raised public consciousness about “public women” who were seen as victims of male domination and their corrupt morals. For excellent research on U.S. anti-vice politics, and the role of the 1910 Mann Act in regulating women and migrants, see Jessica Pliley’s excellent book Policing Sexuality: The Mann Act and the Making of the FBI (Harvard UP). These concerns for vice were ultimately codified in the 1910 International Convention for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic, a document of the League of Nations.

The underlying concerns of the convention grew out of domestic (national) policies aimed at regulating vice (sexual commerce) and a desire to create government coordination in the event of foreign women appearing in commercial sex. The document states:

“Each of the Contracting Governments undertakes to establish or name some authority charged with the co-ordination of all information relative to the procuring of women or girls for immoral purposes abroad … Each of the Governments undertakes to have a watch kept, especially in railway stations, ports of embarkation , and en route, for persons in charge of women and girls destined for an immoral life.”

Significantly, in 1921 the League of Nations revises the convention, named the International Convention on the Traffic in Women and Children. This document brought two important changes to legal doctrine. First, “white slavery” was renamed the “traffic in women” so that all women regardless of race or ethnicity could be seen as possible victims. Second, the term “traffic” signified the importance of women’s movement across borders, and thus shifted focus on “trafficking” from a domestic to international issue.²

The global quest to combat trafficking then stalls, as Europe erupts into war. However, with the establishment of the United Nations, a new convention is produced in 1949, the Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. Retaining the core concern for sexual commerce, the Convention states:

“Whereas prostitution and the accompanying evil of the traffic in persons for the purpose of prostitution are incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person and endanger the welfare of the individual, the family and the community …”

As before, global discourse on trafficking is narrowly focused on sexual commerce. Earlier beliefs about women’s vulnerability remain, as there is no recognition that women may willingly pursue sex work. Thus, “trafficking” is about forcing or coercing women into paid sexual relations. However, the convention remains in place for fifty years without much attention. Signatories to the Convention rarely provide annual reports nor is the issue taken-up forcefully from within the United Nations (though the regulation of sexual commerce continues at national levels). This powerfully changes in the 1970s and 1980s.

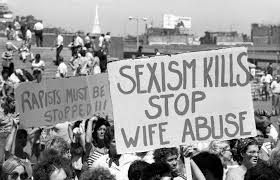

Violence Against Women and Sex Trafficking

Feminist activism, in the United States and globally, started to agitate for greater recognition of “women’s human rights.” While the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights was meant to regard all people, women’s experiences of violence and discrimination were not “seen” as human rights issues. In particular, feminists raised consciousness about violence against women. Working inside and outside of the United Nations, feminists were able to advance an agenda against violence against women — a phrase that is now central to human rights mechanisms and activism across the globe. This organizing began during the UN Decade for Women and was particularly salient in the early 1990s. For an analysis of trafficking, it is particularly important to highlight the impact feminists had on the 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights. At that conference, feminists mobilized to push the core convention to recognize “women’s human rights.” An important tool for that mobilization were the testimonies of the Global Tribunal on Violations of Women’s Human Rights. Women from around the world spoke of the violence and discrimination they experienced. It was a profound testament of the fact that the idea of human rights had been woefully incomplete.

The significance for the evolution of trafficking law is that feminist organizing against violence against women brought heightened attention to what came to be known as “sex trafficking.” This new lens of “violence against women” brought renewed attention to forced prostitution. One of the histories I trace in my book, Economies of Violence, is that of the anti-violence against women activism that shaped how the United Nations doctrine came to define women’s rights and ultimately revitalize attention to the “traffic in women.” However, feminists alone did not return trafficking to the center of global attention. In the early 1990s, there also was a major shift in global migration as the Berlin Wall and USSR were dismantled. Once secure borders opened up just as state socialist economies were radically transformed into markets. The economic policies of shock therapy and the demolishing of state social provisioning brought widespread dispossession and instability. Suddenly, labor migrants from the former Soviet Union were traversing all over Europe and the wider region in search for economic opportunity. And, part of that increased migration and desire for migration brought opportunities for exploitation.

UN Convention on Transnational Crime and Corruption

As the United Nations is altered by feminist activism to recognize violence against women, there is an increase in migration and trafficking coming out of the former “second world.” European governments are particularly concerned as the EU is a primary destination. Women from East European and former Soviet countries who are trafficked come to be called “Natashas.” There is increased concern in the United States as well, as post-Soviet trafficking is the primary example used to pass new legislation in Congress. I will focus just on the UN Convention here. Importantly, the 2000 UN Convention on Transnational Crime and Corruption included three protocols, including regarding trafficking, smuggling, and the illicit manufacturing and trafficking of firearms. The Optional Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children altered international doctrine, while also retaining many of the similar concerns of earlier record. The Protocol states:

As the United Nations is altered by feminist activism to recognize violence against women, there is an increase in migration and trafficking coming out of the former “second world.” European governments are particularly concerned as the EU is a primary destination. Women from East European and former Soviet countries who are trafficked come to be called “Natashas.” There is increased concern in the United States as well, as post-Soviet trafficking is the primary example used to pass new legislation in Congress. I will focus just on the UN Convention here. Importantly, the 2000 UN Convention on Transnational Crime and Corruption included three protocols, including regarding trafficking, smuggling, and the illicit manufacturing and trafficking of firearms. The Optional Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children altered international doctrine, while also retaining many of the similar concerns of earlier record. The Protocol states:

“Trafficking in persons” shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.”

There are three important points to highlight as the Optional Protocol is contextualized in the evolution of anti-trafficking doctrine at the United Nations.

- With the Protocol, the idea of trafficking is expanded to include trafficked labor that is not in sexual commerce. As mentioned earlier, the language of “traffic in women” only regarded women in sex work.

- However, though the concept of human trafficking is broadened in the Protocol, there remains a distinction between forced sexual labor and other forms of forced labor. This is evident in the title as “especially women and children” is given particular emphasis.

- By situating anti-trafficking doctrine within the Convention on Transnational Organized Crime and Corruption, the issue of trafficking is approached primarily as a problem of crime and criminality, rather than primarily as a human rights problem. This has led to a lot of human rights problems within anti-trafficking efforts.

The evolution of anti-trafficking law, as we understand it today, has created many tensions. To end this post, I will mention two. First, given the history of “white slavery” and the “traffic in women,” current anti-trafficking law reinforces social divisions about and government regulatory power over sexuality. Thus, the question of whether women (and men and trans people) willingly choose to engage in sex work remains deeply subsumed under the weight of abolitionist discourse that does not give voice to those engaged in sexual commerce. Second, the primary focus of anti-trafficking doctrine (as in the Optional Protocol) is acutely on the idea of consent. This has created legal distinctions between trafficking and smuggling, for example, where real life distinctions are far more difficult to claim. Thus, in addition to controversies regarding sexual commerce, anti-trafficking doctrine is also riddled with controversies regarding irregular migration and smuggling. The question remains, how to promote human rights and combat forced labor given these complex issues.