By Anne McLaren

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright February 2015)

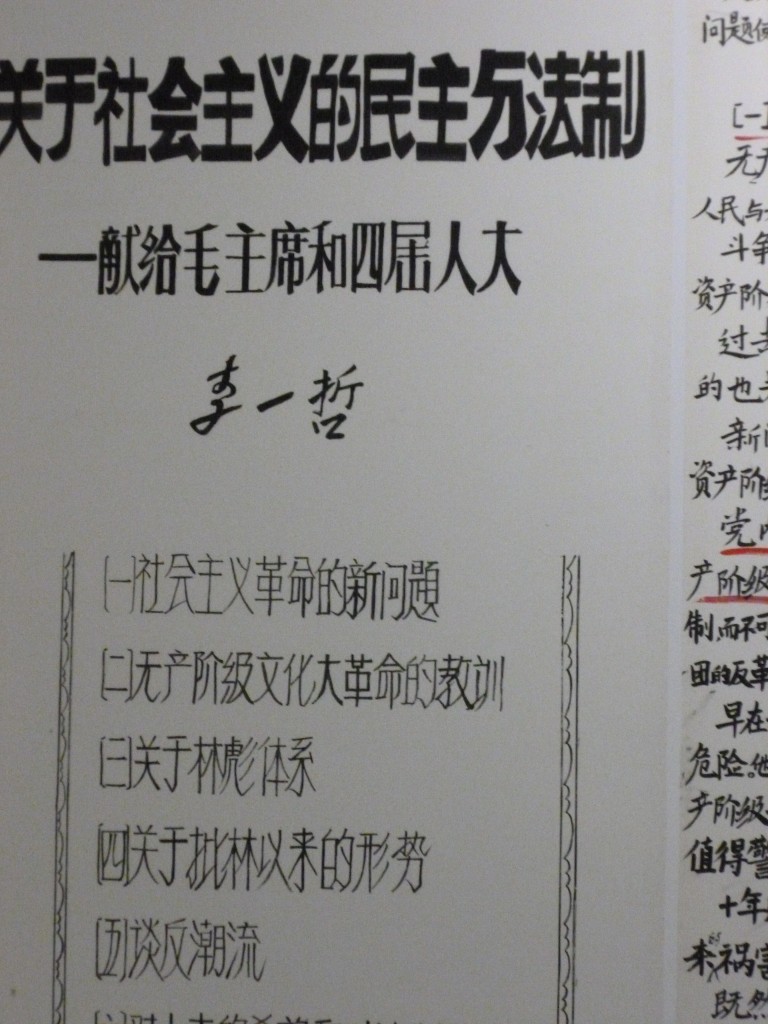

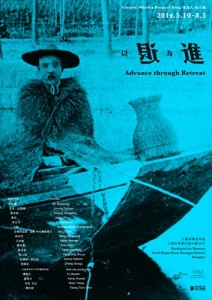

On May 19 2014 I visited the Shanghai Rockbund Art Museum (上海外滩美术馆) to view an exhibition called “Advance through Retreat” (以退为进).[1] The exhibition, curated by the German fine arts scholar Martina Köpper-Yang was spectacular for a number of reasons, but what really amazed me was a recreation in picture frames of the original “Li Yizhe Manifesto” (李一折大字报). The original manifesto comprised a huge dazibao (wall poster) erected in Guangzhou in the dark days of 1974, at the tail-end of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ period. It was entitled, “On Socialist Democracy and Legality” and signed cryptically by ‘Li Yizhe’. This name is an invented one, comprising the first character of the primary author, Li Zhengtian, the second character of the second author, Chen Yiyang, and the third character of the third author, Wang Xizhe.[2]

On May 19 2014 I visited the Shanghai Rockbund Art Museum (上海外滩美术馆) to view an exhibition called “Advance through Retreat” (以退为进).[1] The exhibition, curated by the German fine arts scholar Martina Köpper-Yang was spectacular for a number of reasons, but what really amazed me was a recreation in picture frames of the original “Li Yizhe Manifesto” (李一折大字报). The original manifesto comprised a huge dazibao (wall poster) erected in Guangzhou in the dark days of 1974, at the tail-end of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ period. It was entitled, “On Socialist Democracy and Legality” and signed cryptically by ‘Li Yizhe’. This name is an invented one, comprising the first character of the primary author, Li Zhengtian, the second character of the second author, Chen Yiyang, and the third character of the third author, Wang Xizhe.[2]

Members of the Li Yi Zhe group, 1974. Source: Duli pinglun.

Ostensibly the Li Yizhe manifesto was an attack on the so-called “Lin Biao system” that had allowed Chairman Mao’s seeming heir, Lin Biao, to wield unlimited power until his death in an unexplained plane crash in 1971. The authors denounced Lin Biao’s reign as “fascist” but also claimed that this “fascist” regime continued in the present day. According to the authors, a sinister group had emerged from within the communist party to form a new “social-fascist dictatorship.” The authors demanded the setting up of a new system which they characterized as “socialist democracy and legality” (社会主义的民主与法制).

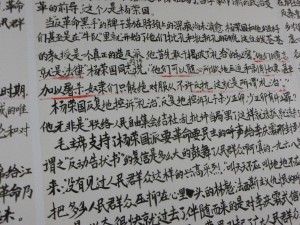

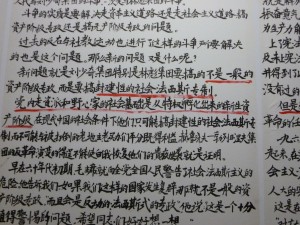

In the 2014 exhibition, these fierce words from the 1970s, denouncing the contemporary rulers as fascists, were underlined in red. How can one interpret the reappearance of this manifesto from forty years ago? Should we see it as a nostalgic retrospective of activism from the distant past that has no relevance in the present? Or did the author of the fresh Li Yizhe manifesto, listed in the catalogue as Li Zhengtian, the original first author, intend us to consider whether the manifesto still has ongoing significance in China of the twenty-first century? According to the catalogue, “the artist… uses a particular political language to push forward the social progress of China.”

The newly-formed Li Yizhe Manifesto was placed along one wall of an upper gallery in the multi-storey exhibition hall. It was arranged to face another set of slogans and wall posters associated with the German Suprematist art movement of the late 1990s. This art installation, designed by Andreas Mayer-Brennenstuhl, comprises a truck in two halves on either side of a grey wall as if driven through the wall.

The two sides of the wall are covered in slogans, photos and flags. A film documenting an art parade in Stuttgart, May 1, 1997, is projected on one side of the wall. Both wall installations, the Chinese and the German, were likely to be equally cryptic to the Shanghai observer in 2014. However, aligned facing each other within this gallery, it appears as if the two forms of discourse, political and artistic, are engaging in dialogue. The Li Yizhe manifesto, originally placed on a wall in the city of Guangzhou, appears here as another type of performance art, an eruption of political activism from the past that still has reverberations in the present. Both types of discourse feature angry denunciations directed at a nebulous enemy and convey an air of understated violence.[3]

Notes:

[1] The title derives from Sunzi’s Art of War.

[2] The authors were 李正天, 陈一阳, and 王希折. For an early report see Simon Leys (Pierre Ryckmans) The Chairman’s New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution. Trans. Carol Appleyard and Patrick Goode, London: Allison & Busby, 1977, pp.234-239. For fuller analysis see Anita Chan, Stanley Rosen, and Jonathan Unger, On Socialist Democracy and the Chinese Legal System: The Li Yizhe Debates. M.E.Sharpe, 1985.

[3] In 1978 Li Zhengtian was set free from detention by the new Guangzhou party boss, a veteran of the Long March called Xi Zhongxun, who just happens to be the father of the current head of the Communist Party in China and Chinese President, Xi Jinping. Is it mere coincidence that we see the Li Yizhe Manifesto re-emerging in the era of President Xi Jinping?