By Ellen Johnston Laing

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright October 2010)

The pictorial Shanghai manhua (Shanghai sketch), published between April 21, 1928 and June 7, 1930, is a mixture of drawings and photographs, with the pictorial inventory ranging from advertisements to social criticism to political caricatures.[ 1 ] Approximately three thousand copies of each eight-page issue were printed, a very high run for that time, attesting to the great popularity of this remarkable pictorial (Bi/Huang 1986: 86). Shanghai manhua was an outlet for the creations of professional cartoonists and sketch masters. Many of their images printed in Shanghai manhua are observations of urban life, but another group of pictures are innovative and unusual visual commentaries on contemporary urban society.

The editorial staff of Shanghai manhua had substantial links with leading representatives of the local literary scene, in particular members of the decadent “neo-sensationist” school (xin ganjue pai), who, inspired by literary trends in Japan, England, and France, espoused a new urban modernity in their poems, short stories, and novels.

This essay first explores the relationships between Shanghai manhua and several of the “neo-sensationist” authors and proposes that the sketch artists were motivated by certain ideas expressed in decadent writings to produce startling, sometimes lurid, images unparalleled in any other Republican era pictorial. The study then gives a brief account of some of the other, more mundane, themes presented in this pictorial.

Several artists who were to publish in Shanghai manhua had already worked together on the small, transitory journal Sanri huabao (orSanri huakan, Three day pictorial), which though ephemeral provided a vehicle for editorial and artistic talents. This pictorial, beginning on August 2, 1925, was published every three days (Wei 1962: 439). It printed popular stories as well as cartoons by Zhang Guangyu (1900-1964),[ 2 ] his brother Zhenyu (1904-1970),[ 3 ] and by other artists, such as Ye Qianyu (1907-1995) (Bi 2002: 107).[ 4 ] When Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition forces arrived in Shanghai in April 1927, Sanri huabao was shut down. Ye and other cartoonists, such as Huang Wennong (1901?-1934),[ 5 ] and Lu Shaofei (1903-1995),[ 6 ] were out of work. They conceived the idea of starting a sketch publication, named Shanghai manhua. The first effort was a lithographed single sheet, which looked like a propaganda poster that could be pasted up (Bi 2002: 107). Because it resembled neither a magazine nor a newspaper, dealers simply discarded it, and so it was lost (Ye 1996: 1).

Undaunted, Ye, Huang, Lu and the others, plus Ding Song (1891-1969/1972)[ 7 ] and Wang Dunqing (1889-1990),[ 8 ] formed the Shanghai Sketch Society in the fall of 1927. The Shanghai Sketch Society was a loose confederation of some eleven like-minded individuals who met for mutual support and to discuss sketching and cartooning. They believed sketches and cartoons should have a purpose and be of use to society. At their meetings, they appraised foreign cartoons and critiqued each other’s efforts. One goal was to publish collections of sketches and cartoons and to produce a sketch magazine (Bi 1982: 48; Xu 1994: 85-86; Bi 2002: 129).

Connections between the Shanghai Sketch Society and local writers were established from the beginning. One Shanghai Sketch Society publication was an album of political cartoons by Huang Wennong, Wennong fengci huaji (Bi/Huang 1986: 81). It had prefaces by Fu Yanchang (1891/92-1961), Wang Dunqing, Xu Weinan (1902-1952), and Li Jinfa (1900-1976) (Bi/Huang 1986: 81, 82). Fu Yanchang and Xu Weinan along with two other “decadent” aesthetes–Zhang Ruogu (1903?-1960?) and Zhu Yingpeng (b. 1895)–were editors of a weekly journal on the arts called Yishu jie (Art world) (Lee 1999: 64).

According to Wang Dunqing, the Shanghai Sketch Society disbanded to focus on publications (Bi 2002: 129), one of which was a renewal of the cartoon pictorial Shanghai manhua. Zhang Guangyu was the linchpin of the Shanghai Sketch Society and its subsequent revival of the Shanghai manhua, which he proposed combine cartoons, sketches, and photography. He found two sponsors to subsidize this new publication: Shao Xunmei (1906-1968) and Zhang Zhenyu (Bi 2002: 107, 295).[ 9 ]

The editorial foreword to Shanghai manhua states the purpose of this publication in modern blank verse form (here presented in my rough translation):

The clash of the Pacific Ocean’s raging waves and typhoons,

Produced Shanghai nestled in the Yellow Sea.

A great life was entrusted to its care and born. Where everything is allowed. Hey!

Splendid fields and gardens, as if a rented pleasure garden.

Great subtle phenomenon, made allowance for old and new, heaven and below.

The conflict between material gain and soul like the remorseful roar of a convict sentenced to death.

The dispassionate twilight, like dry bones in an old tomb.

Promising youth, often spilling their hot blood everywhere.

Today’s seductions, still await judgments from your heart and soul.

Friends, experience this!

We do not want to tamper with the colors, to contaminate mankind’s soul.

There is only experience and expression.

The world’s material civilization goes along with blind teachers [?] and cuts the fucking flesh.[ 10 ]

Evil elements, wear formal dress to invite Shanghai to view a new sham stage play.

Friends, hey, please make an effort!

The great achievements of life. Must be sought out in the great confusion!

The birth of the love of myriad things. Isn’t it like the pot calling the kettle black?

We do not want to be watch-dogs of old Confucian ethical behavior to condemn evil, we are also not interested in praising the vanity of fame and wealth.

The irregular changes of the world is a natural phenomena produced by life’s confusions.

We only endeavor to express the feelings we experience in the greatness and

prosperity of Shanghai’s One Hundred Precious Storehouse (1 [April 21, 1928]: 2).

An analysis of the language used in the manifesto reveals connections to the work of Li Jinfa.[ 11 ] In the literary world, Li Jinfa was “hailed and reviled as China’s first symbolist poet” (Lee 1999: 166; see also Lee 1980: 287-293; Liu 1981: 27-53). Some of the vocabulary in the Shanghai manhua statement of purpose resonates with that employed by Li Jinfa in his 1925 poem “Deserted Woman.” In this poem, “The gushing forth of fresh blood and the sound sleep of dried bones” is echoed in the Shanghai manhua manifesto: “The dispassionate twilight, like dry bones in an old tomb. Promising youth, often spilling their hot blood everywhere.” Li’s “dark night” is similar to the Shanghai manhua manifesto use of “dispassionate twilight.” Both Li and the Shanghai manhua poem refer to the ocean. Li writes: “Together perching on rocks by the roaring sea”; the first line of the Shanghai manhua statement is: “The clash of the Pacific Ocean’s raging waves and typhoons.[ 12 ]

Other affiliations existed between Shanghai manhua artists and Shanghai poets and fiction writers of the “decadent” bent. As noted above, one of the sponsors secured by Zhang Guangyu to subsidize Shanghai manhua was Shao Xunmei. Shao Xunmei was a wealthy, charismatic, and influential writer, poet, translator, book collector, socializer, editor, and publisher based in Shanghai, where his family owned real estate (Lee 1999: 241-254; Hutt 2001). Zhang Guangyu illustrated Shao’s Xiaojie xuzhi (Notice to young ladies) (Shan 1997: 107).

The handsome Shao Xunmei was not only a sponsor of Shanghai manhua, his image was frequently published in Shanghai manhua in varied guises: in one photograph, he is dressed in a bathing costume (along with his wife) (68 [Aug. 10, 1929]: 3); in aother, he is next to bust of his own likeness sculpted by Jiang Xiaojian (51 [April 13, 1929]: 3); and he is also pictured in a silhouette by Wan Laiming (b. 1899) (101 [April 5, 1930]: 3).[ 13 ] Shao’s name appears in an advertisement for one of his artistic ventures opened jointly with several members of theShanghai manhua staff (84 [Nov. 30, 1929]: 7).

Aubrey Beardsley’s scandalous Yellow Book along with writings of the decadent school, such as those by Wilde, Dowson, Swinburne, Symons, Davidson, and Beerbohm were introduced to the Shanghai literary scene by two members of the Creation Society, Yu Dafu (1896-1945) and Tian Han (1898-1968), in 1923 (Zhou 2000-2001: 118). This magazine and Beardsley’s highly erotic drawings were sources of inspiration opening the way in China for a new approach to depicting women and the city, and relations between men and women. Shao Xunmei was so impressed with the Yellow Book that he published his Jinwu yuekan (Gold room monthly) in imitation of it.

In addition to connections with Shao Xunmei, the editors of Shanghai manhua regularly fraternized with Ye Lingfeng (1904-1975), a good friend of Shao, as well as with Mu Shiying (1912-1940), Shi Zhecun (b. 1905), Fu Yanchang, Zhang Ruogu, and the writer Huang Zhenxia (1907-1974).[ 14] Ye, Mu, Shi, Fu, and Zhang, along with Liu Na’ou (1900-1939) were all members of the “neo-sensationist” clique. Writing about Liu Na’ou, Shu-mei Shih (1996: 942) says:

As a cosmopolitan literary project heavily drawn from French and Japanese antecedents, Shanghai modernism prided itself in writing fiction that interweaved urban, exotic, and erotic motifs rendered in experimental style and form that supposedly knew no national boundaries.

Her description could almost be taken as a description of the images in Shanghai manhua.

Shanghai manhua was, of course, not conceived as a literary journal; nearly all the writing printed in it was composed by the magazine editors themselves, plus Huang Wennong and Lu Shaofei. Thus, it is surprising to find in the journal a short story by Fu Yanchang (22 [Sept. 15, 1928]: 6) and a film review by Zhang Ruogu (24 [Sept. 29, 1928]: 7). Most interesting is the fact that writings by Ye Lingfeng were published in Shanghai manhua. These include two collections of casual notes Xinqiu suibi (19 [August 25, 1928]: 7) and Shuangfenglou suibi (48 [March 23, 1929]: 7 and in subsequent issues). His story Chunv de meng (A virgin girl’s dream) began serialization in the Sept. 8, 1928 issue (21: 7). Ye Lingfeng also published translations of works by Maupassant (20 [Sept. 1, 1928]: 7), G. Keller (beginning in 41 [Jan. 26, 1929]: 7), and others.

Fig. 1: Ye Lingfeng, “Untitled.” Shanghai manhua 37 (Dec. 29, 1928), front cover. (click image for a larger version)

Ye Lingfeng has been characterized as “devoted to literary innovation” (Zhang 1996: 208) and his writings as lying somewhere between elite and popular (Liu 2003: 157).[ 15 ] He was an artist as well as a writer and was particularly influenced by Beardsley, although Ye’s line work lacks the supple elegance and polish of Beardsley’s drawing, and Ye’s presentations omit the salaciousness and bite characteristic of Beardsley.[ 16 ]Nonetheless, Ye Lingfeng became known as “China’s Beardsley” (Zhou 2000-2001: 120). Consonant with his literary explorations, Ye did not limit himself to Beardsley, but also ventured into the cubist mode; his 1928 cubist portrait of Lu Xun caused that author to speak scathingly of Ye as a “young revolutionary artist” (Zhang 1996: 208). Ye Lingfeng contributed a cover in cubist style to Shanghai manhua (fig. 1), and to at least one of the magazines he edited, Huanzhou (Mirage).

Apparently, Ye Lingfeng became a Shanghai manhua staff member, and there is little doubt of his substantial influence on the journal in general. More photographs of him (and his wife Guo Linfeng) appear in Shanghai manhua than any other writer of the era, or even any movie star. One anonymous photograph shows Ye Lingfeng and Guo together; photographs of the couple at their wedding and of them in the company of wedding guests were taken by the famous photographer, Lang Jingshan (1892-1995); and separate photographs of each, again taken by Lang Jingshan, were included in the spread honoring the Shanghai manhua staff (30 [Nov. 10, 1928]: 2; 36 [Dec. 22, 1928]: 3; 43 [no date]: 6]. In addition, Guo Linfeng herself submitted a photograph of an eight-year old entertainer (49 [March 30, 1929]: 6). The close contacts between Ye Lingfeng andShanghai manhua personnel are further confirmed by the fact that the initial issue of a new magazine Shidai huabao (Modern miscellany), published by Shao Xunmei, was advertised in late 1929 as having Zhang Zhenyu and Ye Lingfeng as the two editors (78 [Oct. 19, 1929]: 6).

Interpreting Shanghai manhua‘s Images

Analyses of the ideas and writings of the authors mentioned above reveal many themes and ideas directly and indirectly matched by or reflected in the subjects of the Shanghai manhuapictorial program.

For example, Fu Yanchang was convinced that the power of modern Western civilization lay in ancient Greek civilization and that the canons of ancient Greek mythology, along with the German Nibelungenlied and Icelandic sagas were the “essential guidebooks for the aesthetic invigoration of China” (Fruehauf 1993: 138). Fu’s artist counterpart was Zhu Yingpeng.[ 17 ]Zhu declared “we will definitely have to ‘Hellenize’ our ideas!” He emphasized the image of the ideal citizen and physical culture, taking those of ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and Renaissance Europe as his models. Zhu approved of Greek nakedness and condemned the Confucian code, which he held responsible for China’s weakness. According to Fruehauf (1993: 138), Zhu illustrated his declarations with “paintings of stark-naked, victorious pirates who have Herculean bodies attached to their Chinese features. Likewise, his female portraits display the ideal of a full-bosomed Chinese-style Venus, or a vivacious Asian Salome.”

Fig. 2: Zhang Guangyu, “Cubist Shanghai Life.” Shanghai manhua 1 (April 21, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

This Greek connection might have inspired the massively muscled statues of Zhang Guangyu’s cover for the first issue of Shanghai manhua titled “Cubist Shanghai Life” (fig. 2). It shows a sculptured family of four on a plinth: a man and wife rendered as large-scale muscular nudes, a heavy-set youngster, holding a fruit in one hand and seen from the rear, and an infant at his mother’s breast. The group is positioned against a cubist backdrop montage of urban motifs of modernization: automobile, train engine, smoke stacks, electric street lights, and tall buildings. The standing woman looks apprehensively over her shoulder at the city as she nurses her child; the seated man appears utterly dejected as he gazes at the fruit offered to him by his child. The image pits humanity against the city.

Figure 3: Huang Wennong, “Offer Temptation, Receive Infatuation.” Shanghai manhua 2 (April 28, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

Other examples of the “Grecian” influence include a cover by Zhang Zhenyu of two nude wrestlers (5 [May 19, 1928] ). An untitled cover by Lu Shaofei shows a Greek or Roman warrior on horseback; he brandishes a huge sword as his steed steps over a prone vanquished man (33 [Dec. 1, 1928]). “Summer,” a cover by the unidentified Zheng Guanghan, has a voluptuous woman in sheer garb reclining on a pillow-filled couch beneath a palm tree and the moon (66 [July 27, 1929]). In other covers inspired by the perceived notion of the nude as the artistic ideal of ancient Greece, ideally proportioned male nudes are robust and muscular, quite different from the slender physiques of Chinese men. How much these new brawny bodies owe to the ideas of Fu and Zhu remains to be explored.

Leo Lee points out that the “neo-sensationists” school transformed the traditional Chinese woman into someone with more confidence in their “subjectivity as women to the extent that they can play with men and make fools of them in . . . public places.” Speaking of the males in Liu Na’ou’s “Two Men Impervious to Time,” Lee notes that the men “seem to be playthings at the mercy of the self-assured modern heroine” (Lee 1999: 29, 205). The decadent and emancipated woman in Mao Dun’s (1896-1981) Vacillation (1927) admitted that she “only plays with men without ever loving them” (Liu 2003: 82). Around 1933, Mu Shiying even wrote a story titled “The Man who is Treated as a Plaything” (Bei dangzuo xiaoqianpin de nanzi) (Lee 1999: 218).

Fig. 4: Huaisu, “Fascination.” Shanghai manhua 8 (June 9, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

The notion that men were women’s toys was an extremely popular motif for Shanghai manhua artists. Mimicking ancient Egyptian art, the cover of issue two, by Huang Wennong, shows a young man presenting a platter of grapes to a stylized queen seated on a throne; the caption is “Offer Temptation, Receive Infatuation” (fig. 3). The message is men’s unending obsession with and willingness to submit to women, “queens” who treat men as underlings to be toyed with. The theme of women playing with men is reiterated in a cover “Fascination,” by the unidentified Huaisu, in which an elaborately bejeweled, seductive woman has in one hand a long cigarette holder, and in the other, a miniature man kneels in her palm (fig. 4) Another cover (106 [May 10, 1930] ), by Lu Shaofei, depicts a woman teasing a miniature man with a long ribbon, much as one might play with a cat or dog. The title is equally teasing: “Hey, Man. You Better Have the Strength to Chase Me.” In “The Idea of Leisure Time” (73 [Sept. 14, 1929] by Lu Zhixiang (1910-1992),[ 18 ] a woman is surrounded by luxury items; her open purse has scattered cigarettes, a compact and a dance book on the floor; she reclines in a chair and blows smoke rings, her ashtray is supported by a small statue of a man dressed in evening clothes. An anonymous, untitled cover with sexual connotations depicts three tiny men attempting to ascend shapely feminine legs while a fourth man gleefully watches (41 [Jan. 26 1929] ); and in one designed by Zhang Zhenyu, titled “Commodity and Spirit,” a woman holds a man in one hand and a heart in the other (71 [Aug. 31, 1929] ). The motif is carried through inside the magazine. In a sketch by Lu Zhixiang, a nude woman discards one toy man for another (27 [Oct. 20, 1928]: 5).

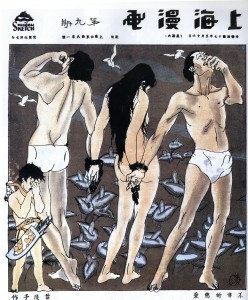

Fig. 5: Ye Qianyu, “Unfortunate Love.” Shanghai manhua 9 (June 16, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

The cigarette, which so many women hold or smoke in Shanghai manhua illustrations, carries sexual connotations when seen in conjunction with its use as an erotic motif by writers such as Mu Shiying. Interpreting a passage in one of Mu’s stories, Leo Lee (1999: 211-212) says Mu uses smoking, along with eating and drinking, as sexual “teases.” Even more cogent is Ye Lingfeng’s cigarette in the following scene from his Unfinished Confession:

I offered her a 555 brand cigarette. Instead of taking it in her hand, she bent over the table and offered me her lips.

“I’d rather be a cigarette!” I could not help saying that while inserting the cigarette between her lips. Looking at these two protruding scarlet petals, I felt an uncontrollable urge of desire burning inside myself. (Zhang 1996: 219)

According to Yingjin Zhang (1996: 209), Ye Lingfeng was obsessed with the love triangle as a plot stratagem. This device underlies several Shanghai manhua covers. In “Between the Two,” a cover created by Fang Xuegu,[ 19 ] a nude woman stands in a glow of light between two contending nude males (25 [Oct. 6, 1928]). In “Unfortunate Love” by Ye Qianyu, two men and a woman are handcuffed together; nearby, Cupid weeps; in the background is a field of blooming calla lilies, clearly sexual symbols (fig. 5).

Fig. 6: Anonymous, “Electric Rabbit and Dog.” Shanghai manhua 18 (Aug. 18, 1928): 4. (click image for larger version)

In her preface to her analysis of the writings of Liu Na’ou, Shu-mei Shih (2001: 278) observes that the Shanghai woman of the late 1920s fiction is considered to be “an unreachable object of desire . . . one can [only] gaze at [her] from a distance, as one looks at a store display window or the image on a screen.” In his study of Liu, Leo Lee (1999: 203) states that a typical plot in Liu’s stories is the man in “hopeless pursuit of a striking-looking modern woman–only to lose out in the end.” Analogous images appear in Shanghai manhua. In one unsigned Shanghai manhua cartoon a man in pursuit of a woman is likened to a dog race: the woman is the never-to-be-caught pace rabbit, the man is the greyhound (fig. 6). An exact visualization of the idea that women can be gazed at but not attained is the Shanghai manhua cover by Zheng Guanghan (99 [March 22, 1930] ) titled “Can Be Gazed at from Afar, But Cannot Be Approached.” It depicts a man looking longingly from his balcony at a girl seated in a neighboring balcony. In a more inventive variation, an untitled cover by Huang Wennong, depicts a woman-goldfish in a glass bowl admired by a seated black-and-white cat-man wearing a collar and bow tie, his fedora and cane nearby (21 [Sept. 8, 1928] ).

These individual motifs and tropes are part of a larger, more intricate web of ideas about the modern woman, about the femme fatale, and about woman as metaphor for the city. The femme fatale as a literary convention has along history in China (e.g., McLaren 1994: 1-16), but the combination of dangerously seductive female with the hard realities of an up-scale, fast-paced, modern city could only be a twentieth-century phenomenon. Writing about the “new woman” who appears in early twentieth-century Chinese popular literature, Perry Link (1981: 214) notes that she

became viewed as another in the general type of woman who exceeded the accepted limits of a woman’s role. This made her, like the others, both inherently interesting and inherently abnormal. In real life, of course, new-style women represented a genuine threat to the traditional order . . . because of the many other aspects of the challenge from the West associated with it.

Continuing to explain the “new-style woman,” Link (1981: 216) says that

When first proposed, the idea of the “new-style” woman in Shanghai was less threatening than it was simply interesting. Western roles in general were new and strange–the “new-style” student, the lawyer, the Western medical doctor, the “revolutionist,” and so on. It was all the stranger and more interesting to see women stand in these new roles, and there were stories galore in the late Ch’ing magazines about “girl students” . . . , “women doctors” . . . , “women revolutionists” . . ., “women spreaders of enlightenment” . . ., and even “women detectives,” “women pilots,” etc.

As Link traces the evolving attitudes toward the “new-style” woman, he concludes that there was a switch toward a negative view that “attention was now less on the outlandishness of what the new-style woman stood for than on the fear that such ideas might actually be implemented. Gradually and quite subtly, the boldness of the new-style woman turned to quaintness, and respect for her to a condescending indulgence.” Link believes this shift took place by 1912, and by that time the new girl student “did more than go beyond proper women’s roles. What she sought to assume was a male role, and a very key male role . . . . She could not be discounted as an oddity . . . because there were ever increasingly numbers of her. Being young she suggested that the future was with her” (1981: 217- 218, 220).

Fig. 7: Ye Qianyu, “Serpent and Woman.” Shanghai manhua 4 (May 12, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

By the mid-1920s, the new-style girl was more active than ever in the public sphere. As seen in the series of photographs in Shanghai manhua and another favorite pictorial of the era, Liangyou huabao (Young companion), young women routinely attended high schools in China; they attended universities at home and abroad; they competed in athletic events; they wore fashionable clothing, often a hybrid of Chinese and Western fashions (Laing 2003); they publicly flaunted their physical charms in the entertainment industry starring in films and in song and dance troupes, or serving as “hostesses” in dance halls. And she became more of a threat than ever as the urban middle-class woman in particular, who smoked, drank, wore up-to-date dresses, expensive jewelry and makeup, went on dates with young dandies, and frequented the dance halls and morphed into the “modern woman.” As defined by Miriam Silverberg (1991: 239) she was “a glittering, decadent, middle-class consumer who, through her clothing, smoking and drinking, flaunts tradition in the urban playgrounds of the late 1920s.” In the view of Yingjin Zhang, who asserts that the terms “new women” and “modern women” were used interchangeably from the 1910s through the 1930s, “new women constitute a new, productive, and yet in many ways disruptive force in modern Chinese society” (Zhang 1996: 188, 189).

Fig. 8: Ye Qianyu, “Untitled.” Shanghai manhua 15 (July 20, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

The modern woman becomes a seductress pursuing her own needs and desires. As a siren femme fatale, she embodies eroticism combined with the commodity commercial culture and exoticism of urban culture. By the same token, she is a metaphor for the temptations and seductions of the city itself: money and sex. Recent assessments of writings by Shi Zhecun and Liu Na’ou clarify and consolidate these ideas. Of Shi Zhecun’s “Pursuit,” Liu Jianmei says that in this story, the bourgeois daughter is portrayed “as a superficial, hypocritical, and erotic femme fatale, the trope of the decadent city before it was conquered by revolutionaries and workers” (2003: 140). Shu-mei Shih asserts that “lodged in [Liu Na’ou’s heroines] are the characteristics of urban culture of the semicolonial city and its seductions of speed, commodity culture, exoticism, and eroticism. Hence the emotions she stimulates in the male protagonist — helpless infatuation and hopeless betrayal–replicate the attraction and alienation he feels toward the city” (1996: 947). And finally, from Yingjin Zhang’s study of the city: “The modern city of Shanghai was frequently gendered as a seductress, not only to the gentleman who saw money and woman as twin temptations but also to the young miss who sought self-intoxication while intoxicating others” (1996: 220, captions to figs. 17-18).

Given these interpretations, it is easy to see how these ideas are translated into visual form in several covers of Shanghai manhua. In the cover for the fourth issue of the magazine by Ye Qianyu, simply titled “Serpent and Woman,” a nude woman in a lascivious pose embraces a smirking coiled serpent (fig. 7). The serpent has a long history in China as a metaphor of a seductive woman, or femme fatale, as in the expression “a beauty as vicious as a snake and a viper” (Lee 1999: 253) and in the well-known “Story of White Snake.”

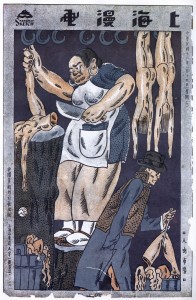

Fig. 9: Lu Shaofei, “Human Meat Market” Shanghai manhua 40 (Jan. 19, 1929), front cover. (click image for larger version)

Women and death are often connected in bizarre, grotesque, and sensationalist Shanghai manhua covers, some epitomizing the link between the twin obsessions of money and sex, plus an added frisson–they lead to death. In “Beauty’s Space,” a cover designed by Wan Laiming, a nude woman holding a skull dances on a coin (10 [June 23, 1928]). The writhing semi-nude woman on an untitled Shanghai manhua cover by Ye Qianyu is disintegrating; her face has already fallen off like a mask to reveal her skull (fig. 8). In “Horrible Love” by Chen Qiucao (1906-1988),[ 20 ] a black-swathed death figure clasps a nude woman to his chest; in one corner is a wine bottle and a glass (23 [Sept. 22, 1928]). Death as a skeleton in a transparent cloak ready to pounce lurks behind a nude woman who is dropping her bracelet, ring, and curling iron into an accumulation of vanity objects: mirror, jewels, perfumes, and peacock feather fan, in the cover by the unidentified Sun Qingyang titled “She, Neglected this Hour” (65 [July 20, 1929]).

Fig. 10: Zhang Zhenyu, “Untitled.” Shanghai manhua 62 (June 29, 1929), front cover. (click image for larger version)

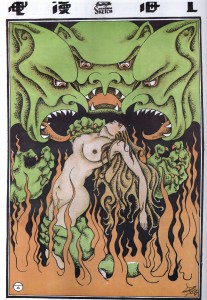

Truly grotesque images commenting on the horrors of prostitution include “Human Meat Market” in a cover by Lu Shaofei, where dismembered female parts are sold to a man by a robust female butcher (fig. 9). A cover by the unidentified Xu Jin, “Pit of Hell” (56 [May 18, 1929]) shows bound, nude women being pitch-forked into flames. One of Zhang Zhenyu’s untitled covers depicts a buxom nude blonde in flames surrounded by three vicious, gap-mouthed, huge-toothed green demons about to devour her (fig. 10). Hutt (2001: 116) interprets this scene as evidence of the Republic era “fascination with decadence. . . The preoccupation with the femme fatale and the end of civilization . . . in the portrayal of the city as an urban dystopia.”

Finally, there is the truly nasty and vicious cover by Zhang Guangyu titled “Degenerate” where a nude blond woman, legs splayed, is suspended up-side-down from a connection at her crotch (fig. 11). The idea has parallels in the writings of Shi Zhecun, who in one story reveled in gory spectacle of the sadistic execution of a seductress and he

Fig. 11: Zhang Guangyu, “Degenerate.” Shanghai manhua 83 (Nov. 23, 1929), front cover. (click image for larger version)

r maid (Lee 1999: 162-163).

It should not, however, be thought that the Shanghai manhua pictorial program consisted solely of salacious, shocking images. Indeed, a large number of sketches in Shanghai manhua depict normal aspects of city life: its amusements, its frustrations, its street life, its contrasts of rich and poor. Many of these more ordinary scenes in Shanghai manhua may strike us today as cliches, but to the Shanghaiese of the late 1920s they must have appeared as wonderfully witty, vividly fresh, or even naughty. Sometimes the cartoons are bland observations, as in that by Ye Qianyu of a woman artist drawing a male model and a male artist using a female model (28 [Oct. 27, 1928]: 4). In a sketch by Zhang Guangyu showing the strap-hangers on a tram, the rotund contours of an obese man and a fat woman mesh (23 [Sept. 22, 1928]: 4). A picture by Lu Shaofei shows a country boy who envisions going to school in Shanghai as a way to meet girls (59 [June 8, 1929]: 5). In “Four Thirty at the Office,” also by Lu Shaofei, men preen as they wait the close of the work day so they can go out on the town (10 [June 23, 1928]: 4).

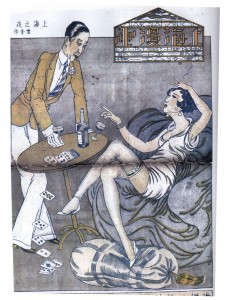

Fig. 12: Huaisu, “Shanghai Night.” Shanghai manhua 13 (July 1, 1928), front cover. (click image for larger version)

The degrading effects of Shanghai nightlife of dance hall, night club, cabaret, and cafe are favorite themes in the Shanghai manhua covers. “Shanghai Night” by Huaisu shows a tipsy woman, her skirt pulled above her garters, collapsed in a chair next to a teetering table covered with playing cards, some of which cascade off the stand, and a tipping wine glass; a slick dandy, still holding his wine glass stands nearby, looking at her as she points at him accusingly (fig. 12). In “One Intoxicated Night,” a cover by Zheng Zhenyu, a woman urges a drunken man to drink; a bracelet in the form of a serpent, a sly hint of the seductive woman, coils around her wrist (98 [March 15, 1930]). The dance hall and its hostesses were frequent sketch subjects. In one by Huang Wennong the dance hall guest pulls back on the hands of a clock; the dance hostess, pulls them forward: “One thinks the clock is too fast, the other thinks it is too slow” (9 [June 16, 1928]: 4). In another dance hall scene, unsigned, in the first panel the hostess dances flirtatiously with a young dandy; she bends one knee in a quick step while pressing close to him and smiling into his face; in the second panel, with an older partner, heavy set and bald, her posture is limp and sluggish, her facial expression is bleak as she looks away from him, and they both perspire from their clumsy exertions (21 [Sept. 8, 1928]: 5). In a cartoon by Huang Wennong titled “4:00 AM Meeting,” a dance hall musician returning home and a silk factory girl going to work pass on the street (9 [June 16, 1928]: 8).[ 21 ]

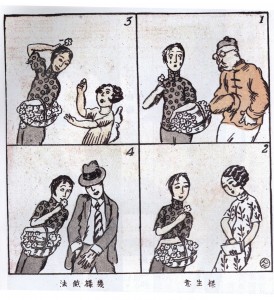

Fig. 13: Ding Song, “Front and Back.” Shanghai manhua 45 (March 9, 1929): 5. (click image for larger version)

Many images focus on men attracted to pretty girls. Pedestrians provided a multitude of opportunities for gentle comment or humor on this worldwide phenomena. In a Ding Song sketch titled “Front and Back,” two men, one wearing traditional Chinese garments and one in Western garb, both with dour faces, approach a pretty woman, after they pass her, their faces are happy (fig. 13). In an unsigned sketch, a dapper man following a good-looking woman is so distracted staring at her that when she turns to look at him, he falls into a manhole (12 [July 7, 1928]: 4). In a four panel cartoon by Lu Shaofei, the sight of a young woman adjusting her garter captivates a bevy of males who follow her down the street (12 [July 7, 1928: 8].

Fig. 14: Lu Shaofei, “Many Ways of Doing Business.” Shanghai manhua 11 (July 1, 1928): 4. (click image for larger version)

Street people are sometimes treated with humor as in the Shanghai manhua four-part cartoon “Many Ways of Doing Business” by Lu Shaofei (fig. 14). A flower vendor grudgingly sells to an old man, is happiest making a sale to a well-dressed lady, teases a child, and coyly smiles when a young gentleman purchases a posy. In a drawing by Zhang Guangyu (16 [August 4, 1928]: 4), heavy-set women with wrinkled faces and baggy clothing bring baskets of tea leaves to sell in the city and meet to chat at the morning market. Here the women are portrayed realistically and sympathetically.

Fig. 15a: Lu Shaofei, “Recent Empresses.” Shanghai manhua 15 (July 29, 1928): 5. (click image for larger version)

Two cartoons sketches by Lu Shaofei and Ye Qianyu in Shanghai manhua designated “Recent Empresses” (i.e., empresses of various feminine professions). In figure 15a, from right to left, the empress of wives of physiognomists, of pheasant street prostitutes, of the dance hall, of the movies, and of Shanghai’s brothel district.

In figure 15b, from right to left: the empress of women students, of opera performers, of women hair dressers, of waitresses, and of women committing suicide in the Huangpu river.

Fig. 15b: Ye Qianyu, “Recent Empresses.” Shanghai manhua 18 (Aug. 18, 1928): 4. (click image for larger version)

These are spoofs of Ye’s drawings of attractive women modeling chic and expensive up-scale fashions that appeared regularly in Shanghai manhua(fig. 16).

The photographs published in Shanghai manhua provide yet a broader view of Shanghai life in the late 1920s with a greater emphasis on reality and less on sensationalism. Opening a typical issue of Shanghai manhua, the reader encountered a series of photographs first on pages two and three, and again on page six. These photographs cover a usual range of urban interests: current events, Chinese and foreign dignitaries, Chinese artists and opera stars, local and foreign movie idols, sports heroes and heroines, as well as men and women students.

Fig: 16: Ye Qianyu, “Summer Fashions.” Shanghai manhua 6 (May 26, 1928): 4. (click image for larger version)

The back page of Shanghai manhua carried the cartoon strip by Ye Qianyu, Wang xiansheng (Mr. Wang), based on the American “Bringing Up Father.” Ye’s “Mr. Wang” featured the trials and tribulations of urban life and became one of the most famous cartoons in China

In conclusion, during its short existence, Shanghai manhua was more than a collection of photographs of contemporary people, biting political cartoons, humorous scenes, mild jokes, along with witty observations and pictorial comments on urban life. The lively cartoon sketches capture the city street and home life in a way that the static photographs cannot.

Although not at all evident in its statement of purpose, the magazine functioned to a certain extent as a counterpart to the writings of members of the “neo-sensationist” literary school. Given the close associations of the magazine’s editors and members of this school, Shanghai manhua served as another outlet for the new sensational and decadent ideas of several leading writers in Shanghai at the time. The images in Shanghai manhua, plus the writings of Ye Lingfeng in particular, then combined to create a unique statement about contemporary attitudes toward urban life and about urban women in particular, unmatched by any other popular magazine of that era.

Through its striking and sometimes shocking covers, its vivid sketches of urban life, and its array of photographs, Shanghai manhua presented a singular view of the city welcomed by those appreciative of its special fascinations. It was the unique combination of images, from those inspired by decadent writers, to the more mundane scenes of city life, to the photographs of actual city dwellers, to the back-page cartoon of “Mr. Wang” that made Shanghai manhua irresistible to the elite Shanghai audience and help account for its extraordinary popularity

Ellen Johnston Laing

University of Michigan

Notes:

[ 1 ] Shanghai manhua was reprinted in a two volume photocopy edition published by Shanghai shudian chubanshe in 1996. References are to this photocopy edition.

[ 2 ] Zhang Guangyu, a native of Wuxi, Jiangsu province, studied at home and at age fourteen went to Shanghai where he enrolled in the school attached to the Shanghai Second Normal College. After graduation, he studied with Zhang Yuguang (1885-1968; not a relative), the prestigious multi-talented Shanghai artist (Laing 2004: 140). Zhang Guangyu created illustrations for romance fiction magazines between 1918 and 1922 and contributed pictures to Shijie huabao (World pictorial), a journal lasting only ten issues (Wei 1962: 321). In 1919, Zhang Guangyu was the editor of Huaji huabao (Comic pictorial), another short-lived publication (only two issues). In this same year, Zhang Guangyu joined the Shengsheng Art Company, publishers of Shijie huabao with Ding Song as editor and himself as assistant editor. Between 1921 and 1925 Zhang Guangyu worked in the advertising department of the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company, where, in addition to drawing advertisements, he also provided calendar poster pictures (Laing 2004: 191-198). In 1925, Zhang was involved with publication of the Shanghai huabao and in 1926 he transferred to the Shanghai Mofan Factory, doing art work and managing the Sanri huabao (Wang 1988: 279-281).

[ 3 ] Zhang was self-taught in art; he became a specialist in cartoons and decoration (Ma et al. 1992: 385).

[ 4 ] Ye Qianyu was born in Tonglu, Zhejiang province. At age 15, he entered the middle school administered by the Salt Administration in Hangzhou where he belonged to an art group (Shan 1997: 1). He never received formal art education. 1926 found him in Shanghai where he worked first as a shop assistant selling cloth and then later for the Japanese Sanyou company designing advertisement pictures. He left Sanyou to produce illustrations for elementary school science texts and advertisements for the display windows of Zhongyuan Press. In late 1926, the Zhongyuan Press ceased publishing science books and Ye lost his job. Friends from Sanyou found him a position at a textile factory where Ye lasted two months. Zhang Zhenyu discovered his situation and offered him a post on the staff of Sanri huabao to assist with planning and page layout, and to oversee its printing (Shan 1997: 57, 62, 64, 68, 72).

[ 5 ] Huang Wennong was born into a poor family in Songjiang county, Shanghai. His father was a servant in the Jesuit church; his mother took in laundry and served as a children’s nurse. In the Huang family, there were five mouths to feed and so young Wennong, after graduating from elementary school, was apprenticed at age sixteen to a lithographer at the Zhonghua Press in Shanghai. Huang’s artistic talents caught the attention of the magazine Xiao pengyou (Little friends). He appointed Huang art editor of Xiao pengyou. Around 1924 or 1925 Huang’s political and social cartoons were published in Jingbao (Crystal) and Dongfang zazhi (Eastern Miscellany) (Bi 2002: 276-277; Bi/Huang 1986: 76-82).

[ 6 ] Lu Shaofei was a native of Shanghai; his father was a folk artist who specialized in painting pictures of traditional gods. Lu followed his father in art and excelled at sketching. At age 17, he briefly studied at the Commercial Press (art school?) and contributed several cartoons to Shenbao. Lu entered the Shanghai Art Academy, but was forced to withdraw because of a lack of funds to pay tuition. He joined the Dawn Art Society, formed in 1921 by Zhang Yuguang and other artists interested in studying Western art (Xu 1994: 44-45). In 1923 Lu Shaofei provided pictures for Shengsheng huabao (Shengsheng pictorial) (Bi/Huang 1986: 113-116; Bi 2002: 117-119).

[ 7 ] Ding was a native of Jiashan, Zhejiang province. As a youngster, he was interested in art and when older studied with Zhou Xiang (1871-1933), one of the first Chinese to promote training in Western art through a formal schooling. Ding initially studied Western art and sketching, then pursued Chinese-style figure painting. He taught in art schools in Shanghai for several years and eventually was hired by British American Tobacco as a staff artist to design their advertisements. His cartoons were carried in local newspapers, such as Xinwen bao,Shenbao, as well as in Shanghai huabao (Shanghai pictorial) and Sanri huakan (Wang 1948: 1; Ma et al. 1992: 5; Xu 1992: 5; Wang 1988: 262-263).

[ 8 ] Wang Dunqing was born in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province. In 1923, he graduated from St. John’s University with a major in literature; he became a noted English translator. He made his first cartoon in 1923, worked for Shanghai huabao, and participated in the activities of the Creation Society literary group. As a cartoonist, he was influenced especially by English cartoon manuals and by the Japanese cartoonist, Fuben Ippei (Ma et al. 1992: 110; Xu 1992: 152; Bi 2002: 128).

[ 9 ] Although the romanization is identical to the name of the artist, the Chinese characters of the personal name are different. I have been unable to identify this person.

[ 10 ] This may refer to the expression “to cut out the flesh to cure a boil,” i.e. the remedy is worse than the disease (Williams 1920: 67).

[ 11 ] Li was a sculptor from Meixian, Guangdong province who studied in France (Wang 1988: 303-304; Xu 1992: 42).

[ 12 ] Translations of Li’s poem from Yang 1987: 222, 223. The fact that Li might be using the traditional Chinese poet’s approach of adopting a woman’s voice to express his feelings raises a question about the Shanghai manhua manifesto which remains to be explored.

[ 13 ] Wan Laiming was born in Nanjing. Self-taught in art, he worked for the Commercial Press and as an art editor for the pictorial Liangyou huabao (Young companion); Wan and his two brothers were pioneers in the animated film in China (Zhongguo meishuguan 1993: 243; Leyda 1972: 384).

[ 14 ] See Shan 1997: 105. For Mu, see Liu 2003:147-152 and Shih 2001: 302-338. For Shi, see Lee 1999: 154-189, Liu 2003: 138-141; Shih 2001: 339-370. For Fu, see Fruehauf 1993: 137-141. For Zhang Ruogu, see Lee 1999: 20-23. Freudian influences in the writings of Shi, Liu, Mu, and Ye Lingfeng are discussed by Zhang 1992: ch. 4. For Huang, see Chen 1993: 815. Ye, Mu and Shi were also members of the later literary group, Les Contemporaines.

[ 15 ] Other studies of Ye Lingfeng’s literary output are in Lee 1999: 255-265 and Zhang 1996: 207-223.

[ 16 ] Examples of Ye Lingfeng’s art work are scattered throughout Chuangzao yuekan (Creation), the journal of the Creation Society, which continued publication under similar titles from 1922 to 1928.

[ 17 ] From Zhejiang province, Zhu was a founding member of the Dawn Art Society and was extremely active in teaching art in Shanghai art schools during the nineteen twenties and thirties (Wang 1948: 18; Zhu and Chen 1989: 228).

[ 18 ] Lu Zhixiang graduated in 1927 from the Suzhou Art Academy (Zhongguo meishuguan 1993: 293-294).

[ 19 ] Fang Xuegu was among the four former students of Liu Haisu (1896-1994) who in 1928 established the White Goose Painting Society (later known as White Goose Western Painting Institute) in Shanghai (Laing 2004: 202-203).

[ 20 ] Chen’s family was from Yinxian in Zhejiang province, but lived in Shanghai. He attended Liu Haisu’s Shanghai Art Academy and in 1928, along with Fang Xuegu and others founded the White Goose Painting Society (Ma et al. 1992: 404-405; Zhu/Chen 1989: 244-246).

[ 21 ] The contrast of a party-goer returning home at dawn and a working girl going to work was also a trope in films of the era (Zhang 1996: 200).

Glossary:

“Bei dangzuo xiaoqianpin de nanzi” 被當作消遣品的男子

Chen Qiucao 陳秋艸

Chuangzao yuekan 創造月刊

Chunv de meng 處女的夢

Ding Song 丁悚

Dongfang zazhi 東方雜誌

Fang Xuegu 方雪鴣

Fuben Ippei 風 本一平

Fu Yanchang 傅彥長

Guo Linfeng 郭林鳳

Huaisu 懷素

Huaji huabao 滑稽畫報

Huang Wennong 黃文農

Huang Zhenxia 黃振 (or 震) 遐

Huanzhou 幻洲

Jiang Xiaojian 江小鶼

Jingbao 晶報

Jinwu yuekan 金屋月刊

Lang Jingshan 郎靜山

Liangyou huabao 良友畫報

Li Jinfa 李金髮

Liu Haisu 劉海粟

Liu Na’ou 劉 吶 鷗

Lu Shaofei 魯少飛

Lu Zhixiang 陸志庠

Mao Dun 矛盾

Mu Shiying 穆 時英

Sanri huabao 三日畫報

Sanri huakan 三日畫刊

Shanghai huabao 上海畫報

Shanghai manhua 上海漫畫

Shao Xunmei 邵洵美

Shenbao 申報

Shengsheng huabao 生生畫報

Shidai huabao 時代畫報

Shijie huabao 世界畫報

Shi Zhecun 施蟄存

Shuangfenglou suibi 雙鳳樓隨筆

Sun Qingyang 孫青羊

Tian Han 田漢

Wang Dunqing 王敦慶

Wang xiansheng 王先生

Wan Laiming 萬籟鳴

Wennong fengci huaji 文農諷刺畫集

Xiaojie xuzhi 小姐須知

Xiao pengyou 小朋友

xin ganjue pai 新感覺派

Xinqiu suibi 新秋隨筆

Xinwen bao 新聞報

Xu Jin 徐進

Xu Weinan 徐蔚南

Ye Lingfeng 葉 靈鳳

Ye Qianyu 葉淺予

Yishu jie 藝術界

Yu Dafu 郁達夫

Zhang Guangyu 張光宇

Zhang Ruogu 張若谷

Zhang Yuguang 張宇光

Zhang Zhenyu 張振宇 (Zhengyu 正宇)

Zhang Zhenyu 張珍虞 (unidentified)

Zheng Guanghan 鄭光漢

Zhou Xiang 周湘

Zhu Yingpeng 朱應鵬

Bibliography:

Bi Keguan 畢克官. 1982. Zhongguo manhua shi hua 中國漫畫史話 (Talks on the history of Chinese cartoons). Ji’nan: Shandong renmin.

—–. 2002. Manhua de huayuhua: bainian manhua jianwen lu 漫畫的話與畫: 百年漫畫見聞錄 (Cartoon conversations and pictures: a record of experiences of one hundred years of cartoons). Beijing: Zhongguo wenshi.

—– and Huang Yuanlin 黃遠林. 1986. Zhongguo manhua shi 中國漫畫史 (A history of Chinese cartoons). Beijing: Wenhua yishu.

Chen Yutang 陳玉堂, comp. 1993. Zhongguo jinxiandai renwu minghao da cidian 中國近現代人物名號大辭典 (Dictionary of names and styles of people from recent and modern times). Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji.

Fruehauf, Heinrich. 1993. “Urban Exoticism in Modern and Contemporary Chinese Literature.” In Ellen Widmer and David Der-wei Wang, eds., From May Fourth to June Fourth: Fiction and Film in Twentieth-Century China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 133-164.

Hutt, Jonathan. 2001. “La Maison D’or–The Sumptuous World of Shao Xunmei.” East Asian History 21: 111-142.

Laing, Ellen Johnston. 2003. “Visual Evidence for the Evolution of ‘Politically Correct’ Dress for Women in Early Twentieth Century Shanghai.” Nan nu: Men, Women and Gender in Early and Imperial China 5, no. 1: 69-114.

—–. 2004. Selling Happiness: Calendar Posters and Visual Culture in Early-Twentieth-Century Shanghai. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Lee, Leo Ou-fan. 1980. “Modernism in Modern Chinese Literature: A Study (Somewhat Comparative) in Literary History.” Tamkang Review 10, no. 1 (Spring): 281-307.

—–. 1999. Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China 1930-1945. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Leyda, Jay. 1972. Dianying Electric Shadows: an Account of Film and the Film Audience in China. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Link, Perry. 1981. Mandarin Ducks and Butterflies: Popular Fiction in Early Twentieth-Century Chinese Cities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Liu, David Jason. 1981. “Chinese ‘Symbolist’ Verse in the 1920s: Li Chin-fa and Mu Mu-t’ien.” Tamkang Review 12, no. 1 (Fall): 27-53.

Liu Jianmei. 2003. Revolution Plus Love: Literary History, Women’s Bodies, and Thematic Repetition in Twentieth-Century Chinese Fiction. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Ma Xuexin 馬學新, Cao Junwei 曹均偉, Xue Liyong 薛理勇, and Hu Xiaojing 胡小靜, comps. 1992. Shanghai wenhua yuanliu cidian 上海文化源流辭典 (Dictionary of Shanghai culture). Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexueyuan.

McLaren, Anne E. tr. and intro. 1994. The Chinese Femme Fatale: Stories from the Ming Period. University of Sydney East Asian Series no. 8. Broadway, Australia: Wild Peony.

Shan Feng 山風, ed. 1997. Ye Qianyu zixu 葉淺予自敘 (Ye Qianyu memoirs). Beijing: Tuanjie.

Shih, Shu-mei. 1996. “Gender, Race, and Semicolonialism: Liu Na’ou’s Urban Shanghai Landscape.” Journal of Asian Studies 55, no. 4 (Nov.): 934-956.

—–. 2001. The Lure of the Modern: Writing Modernism in Semicolonial China, 1917-1937. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Silverberg, Miriam. 1991. “The Modern Girl as Militant.” In Gail Lee Berstein, ed., Recreating Japanese Women, 1600-1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 239-266.

Wang Bomin 王伯敏 ed. 1988. Jinxiandai meishu 近現代美術 (Modern art) vol. 7 of Zhongguo meishu tongshi 中國美術通史 (Compendium of Chinese art). Ji’nan: Shandong jiaoyu.

Wang Yichang 王扆昌 ed. 1948. Zhonghua minguo sanshiliu nian Zhongguo meishu nianjian 中華民國三十六年中國美術年鑒 (1947 yearbook of Chinese art). Shanghai: Shanghaishi wenhua yundong weiyuanhui.

Wei Shaochang 魏紹昌. 1962. Yuanyang hudiepai yanjiu ziliao 鴛鴦蝴蝶派研究資料(Research materials on the mandarin duck and butterfly school). Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi.

Williams, C. A. S. 1920. A Manual of Chinese Metaphor: Being a Selection of Typical Chinese Metaphors, with Explanatory Notes and Indices. Shanghai: The Commercial Press.

Xu Zhihuo 許志活. 1992. Zhongguo meishu qikan guoyan lu (1911-1949) 中國美術期刊過眼錄 (Record of Chinese art periodicals 1911-1949). Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua.

—–. 1994. Zhongguo meishu shetuan manlu 中國美術社團漫錄 (Brief accounts of Chinese art groups). Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua.

Yang, Vincent. 1987. “From French Symbolism to Chinese Symbolism: A Literary Influence.” Tamkang Review 17, no. 3: 221-243.

Ye Feng 葉風. 1996. “Zhongguo manhua de zaoqi zhengui wenxian: ‘Shanghai manhua.’ ” 中國漫畫的早期珍貴文獻: 上海漫畫 (Chinese cartoons earliest precious document:Shanghai manhua). In Shanghai manhua, reprint, Shanghai: Shanghai shudian, 1: 1-3.

Zhang, Jingyuan. 1992. Psychoanalysis in China: Literary Transformations 1919-1949. Ithaca, NY: East Asia Program, Cornell University.

Zhang Yingjin. 1996. The City in Modern Chinese Literature and Film: Configurations of Space, Time, and Gender. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Zhongguo meishuguan 中國美術館, ed. 1993. Zhongguo meishu nianjian 1949-1989 中 國美術年鑒 1949-1989 (China art yearbook, 1949-1989). Guilin: Guangxi meishu.

Zhou Xiaoyi. 2000-2001. “Beardsley, the Chinese Decadents and Commodity Culture in Shanghai During the 1930s.” Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia 32-33: 117-134.

Zhu Boxiong 朱伯雄 and Chen Ruilin 陳瑞 麟. 1989. Zhongguo xihua wushi nian: 1898-1949 中國西畫五十年 (Fifty years of Western painting in China 1898-1949). Beijing: Renmin meishu.