A Conversation between Christopher Rea and Henry Jenkins

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright August 2017)

Slapstick performance and trick cinematography dominated early global cinema. People climb into boxes and are tossed around; they jerry-rig all manner of dwellings and conveyances; they leap out of windows, crash through doors, dangle from clock towers, and slide down staircases; they appear and disappear like ghosts. But what did such visual gags look like in films made in Shanghai, as opposed to Los Angeles? How did filmmakers from different cultural traditions share or adapt comic tropes—and which ones? And how did their comedy change with technology, such as the advent of sound cinema, or with politics, war, and revolution?

The following conversation between Henry Jenkins, a media scholar who works primarily on American popular culture, and Christopher Rea, a cultural historian of China, explores comic convergences on the silver screen, focusing on filmmakers who embraced a vaudevillian aesthetic of visceral comedy and variety entertainment. It offers a guided tour of cinematic comedy in comparative perspective, drawing out resonances between Hollywood and Chinese films from the 1910s to the 1950s. Illustrating the discussion are clips from a variety of films, from early works by Charlie Chaplin to the short-lived era of cinematic satire in Mao’s China.

Christopher Rea is Associate Professor of Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia. He is author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (California, 2015), which won the 2017 Joseph Levenson Book Prize (post-1900 China) of the Association for Asian Studies.

Henry Jenkins is Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at the University of Southern California and is author of more than fifteen books about various aspects of American media, including What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic (Columbia, 1989).

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Christopher Rea and Henry Jenkins that took place at the University of Southern California on March 2, 2016. The event was co-sponsored by the USC Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, and the Department of Asian Studies of the University of British Columbia, and was made possible thanks to the assistance of Professor Brian Bernards and Brianna Correa. Nick Stember created the transcript, which has been edited for length.

A full video of the event (104 minutes), which was produced by the USC U.S.-China Centre, is available on YouTube as: “Christopher Rea and Henry Jenkins on how vaudeville differed between Hollywood and China.”

I’ve always been a fan of Monty Python and the Marx Brothers, but Henry Jenkins’ book What Made Pistachio Nuts? (fig. 1) really helped me understand how you can write about comedy in an interesting and meaningful way. I want to thank Paize Keulemans, currently at Princeton, who introduced me to What Made Pistachio Nuts? and also let me borrow “The Ancient Art of Falling Down” for the title of today’s event—he’d written a conference paper about Jackie Chan and how he used stunts from Buster Keaton (1895-1966) and Harold Lloyd (1893-1971) (fig. 2), the early sound comedians who Henry Jenkins writes about. So I’m very interested in comedy and laughter as a type of culture, and I’m interested in exploring its literary dimensions, and its cinematic dimensions.

While researching The Age of Irreverence, when I trolled to see what types of publications were out there, I came across a lot of humor magazines (fig. 3), some in Chinese, some in French, some in English, some in multiple languages, like Shanghai Puck, which was in both English and Chinese. During this period, China was transitioning from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) to the modern nation-state the Republic of China (est. 1912). Why was this historical moment accompanied by so much laughter, satire, and parody?

I was interested in humor partly as a phenomenon spurred by a big boom in print media, where you also have things like humor collections (fig. 4) filled with jokes, essays, poetry and other materials. Hundreds of them came out between the 1890s and the 1930s. This period of social turmoil and regime change was accompanied by a proliferation of laughter, including in ephemera, like pulp and sub-literary products.

But laughter was something that crossed a big socio-economic spectrum, involving educated elites as well as hacks and entrepreneurs. It was a very broad field with different manifestations of laughter that congealed into what you could call “comic cultures.” Chinese comic cultures were not tightly bound—they were heavily influenced by international trends. Henry Jenkins has written about this extensively, and we decided to do a bit of a mash-up between some of my research and some of his research. We’ll intersperse our conversation with still images and clips from the types of films we’ve worked with.

Henry Jenkins: I was going to tell a little of my story, that I got fascinated with this tradition of slapstick comedy. I was sick in bed with fever almost three decades ago, and ended up watching a film called Stand Up and Cheer! (1934), that’s a totally forgotten film, but in the midst of the film there’s a sequence where these very-Frank Capraesque senators investigate a government agency. And the bureaucrats leave the room and suddenly the two senators burst into backflips, saying things like “What made pistachio nuts?” And they’re rolling on the floor with each other, and knocking their heads together, and so forth. It’s all very broad physical comedy, and then the bureaucrats come back into the room and they sit up straight and act very dignified. I just couldn’t figure the scene out! And it led me down this path of realizing that these two actors were vaudevillians, Frank Mitchell and Jack Durant, who were performing in this film. And the film itself is strange in any number of ways, but that scene of the back-flipping senators took me down this path to really think about vaudeville as a tradition in American entertainment.

What we see here are just a range of images of classic vaudeville (fig. 5). The guy hanging off the table is one of the Three Keatons—the small boy next to the table is actually Buster Keaton as a young man, who would go on to become famous as a slapstick comedian. The intensity and insanity, the spectacle, the virtuosity of vaudeville becomes a driving force in American comedy during this same period that Christopher is talking about in his work. And it’s part of a larger change in what comedy means in American culture.

I’m going to read a couple of quotes from my book, What Made Pistachio Nuts?

The first quote comes from the late nineteenth century:

The great men who dared to laugh in an earlier age than ours laughed in moderation. . . They held folly up to ridicule, not to amuse the groundlings, but to reveal, in a sudden of blaze of light, the eternal truths of wisdom and justice. . . They did not at every turn slap their reader on the back and assure him that there is nothing congruous in the visible world. . . They kept their humor in its proper place; they used it for a wise purpose; they did not degrade it for an easy round of applause.

The next comes from an instructional guide for vaudeville gag writers written by Brett Page:

The purpose of the [comic] sketch is not to leave a single impression of a single story. It points no moral, draws no conclusion, and sometimes it might end quite as effectively anywhere before the place in the action at which is does terminate. It is built for entertainment purposes only and furthermore, for entertainment purposes that end the moment the sketch ends.

So what we’re seeing is this friction, a moment of shift, in the function of comedy from being a tool in moral instruction to being something for mass amusement. Moral instruction was tied to particular class perspectives and status, and with this shift, comedy is going to be for everyone—a more inclusive audience consisting of working classes as well as the learned classes. And the success is determined by whether people laughed. In vaudeville each act is self-contained, the performers are developing their own material. The theatre owner files a card reporting on how well the act went over. So he’s looking for signs from the audience of an emotional response, and he literally writes down a report on a card and sends it in. So the performer is looking for the “wow climax,” which is a term from the period—the moment that you get the maximum emotional response. The vaudeville stage is a machine to generate heightened emotion. It may be weeping, it may be patriotism, it may be gasps and wows, it may be laughter, but you’re trying to draw that response out and insure that is a shared experience across the house.

This image (fig. 6) shows Steeplechase Park at Coney Island, one of the early amusement parks in America. And note that it’s called “The Funny Place,” not even “The Fun Place.” Other parks of the period might target “Children of All Ages” or today, Disneyland bills itself the “Happiest Place on Earth.” But it’s specifically “funny” and its icon is that of the smiling and laughing face, again evoking particular emotional responses as the measure of success.

Vaudeville is a performance centered mode of entertainment. An actor seeks to blend into a character. As a vaudevillian, you become, first of all, adept at putting on and taking off masks. And these performers who come from diverse ethnic backgrounds begin to think of ethnic and racial masks as identities they can put on and take off. So all of the pictures here (fig. 7) are of Eddie Cantor (1892-1964) from his various film roles.

You see Eddie Cantor in black face, Eddie Cantor as a Native American, Eddie Cantor in drag, Eddie Cantor as a Roman, Eddie Cantor as a Spanish matador . . . so these were different roles or identities Cantor played at various points in time. Ironically, after about 1930, the one role he can’t play is Jewish. He’s actually Jewish, and his early films reference his Jewishness, but starting in about 1930 they strip it away. He’s suddenly Russian, not Jewish. This guy who was raised over a delicatessen on the lower East Side does an ad campaign for Wonder Bread, just to escape the stigma of being Jewish as Hollywood seeks to broaden the market for his films. And from that point forward, the only reference to Judaism that crops up in Cantor’s films is a moment where he’s in Egypt, he’s been kidnapped, and he turns to the Egyptian and says “Let my people go!” And that turns immediately into a blackface minstrel number singing it as a serial. And so the Southern colonel they’re with and Cantor blacken up and immediately sing “Let my people go.” The joke transforms from a winking acknowledgement of Jewishness into something that’s going to be recognized as yet another mask that he takes on and puts off.

As people are trying to build mechanisms for generating laughter, they draw on a stimulus response model, straight out of Pavlov. So this is Joe Weber (1867-1942) and Lew Fields (1867-1941) (fig. 8), who are the first comic pair of fat and thin to really dominate on vaudeville.

They play Dutch characters, which is another one of those ethnic types. They wrote a piece about their comedy:

An audience will laugh loudest at these episodes:

when a man sticks one finger into another man’s eyes;

when a man sticks two fingers into another man’s eyes;

when a man chokes another man and shakes his head from side to side;

when a man kicks another man;

when a man bumps up suddenly against another man and knocks him off his feet;

when a man steps on another man’s foot.

Human nature—as we have analyzed it, with results that will be told by the cashier at our bank—will laugh louder and oftener at these spectacles, in the respective order we have chronicled them, than at anything else one might name. (What Made Pistachio Nuts?, page 35)

I mean, they’re joking but they’re using this language of science and affect to describe this behavior. So comedians use a language of stimulus response, how we evoke laughter from an audience through these fragmentary bits of stock business that can be added up and put into a context to form a sketch. Unlike the Victorian notions of humor, there is no moral message, only the pleasure of watching a man poke two fingers into another man’s eyes, shake his head about, make him fall down.

Rea: One of the things that struck me in comparing what was going in China and what was going on in other places like the United States was that in late nineteenth and early twentieth century China cultural confidence was not high; it was at a low ebb. People were talking about China as a nation going extinct, because of all the pressures from foreign powers: the Japanese were there, and there were territorial concessions to Britain, France, and the US, in places like Shanghai. China was a country divided.

I called my book The Age of Irreverence partly because a lot of the old authorities had lost their prestige. Laughter was a symptom, but also a mechanism, for further eroding their authority and expressing skepticism towards received wisdom. At the same time, in comic films and comedic literature and criticism of the period, we hear a lot of voices working against it. Some are moralizing voices that to us now seem patronizing and archaic, like Henry’s quote about the “great men of old” who “laughed in moderation.” Some people were worried that laughter would further erode the Chinese nation-state and push it into an abyss. Yet the ethos of irreverence was liberating to others, who felt like they would actually gain confidence by trying more experimentation.

Mutt and Jeff (fig. 9), for example, was a very influential turn of the twentieth century or early twentieth century comic strip in the US, widely serialized and read by millions, including by people in China. I found Mutt & Jeff iconography in old Chinese magazines (fig. 10).

I haven’t tracked down whether this is an imitation of an actual Mutt and Jeff strip, or whether the Chinese illustrator just used the same iconography to create a new series, but we see a lot of this sort of experimentation in the early twentieth century. In the 1920s and 1930s, Chinese cartoonists began creating their own serial characters, like Mr. Wang by Ye Qianyu. Mr. Wang became the first successful franchised Chinese comic figure—movies were even made based on the character.

Fig. 11: An American cartoon reprinted with a Chinese caption in the 1930s Shanghai magazine The Analects Fortnightly

Chinese publishers also directly imported and translated cartoons from The Humorist, The New Yorker (fig. 11), and other foreign media outlets, and these became part of Chinese humor culture. Humor was not bounded off, with a Chinese sense of humor over here and an American sense of humor over there. It was very eclectic, there was quite a lot of mixing going on.

Jenkins: Having seen that previous image, I got these images out (fig. 12), which come from the American slapstick tradition. The bottom is Rube Goldberg, whose name is still synonymous with these improbable mechanical devices where an enormous amount of energy is expended to accomplish very little, and above-right we see Chaplin in Modern Times where he has an efficiency device that’s being made fun of, where the worker doesn’t have to stop working in order to be fed, the assembly line work must go on.

The other one there on the top left is lesser known, it’s Charley Bowers (1889-1946) whose work is just beginning to be discovered by scholars of slapstick. It was forgotten for the better part of the twentieth century, but it’s now been recovered from archives, you can now view a DVD, but Bower’s comedies are all about devices, mechanical objects, how you create things—how you use the modern era to do improbable and unlikely things.

Rea: A related question is how to trace cultural flows between different places. Cinema scholars have led the way in identifying the vocabulary and grammar of film: the memes, stock scenarios and motifs that occur again and again. Memes also appear in cartoons, especially after the explosion of cartooning in China in the late 1920s. In 1928 a new government was established in Nanjing and China’s political situation became a bit more stable. The Warlord Era had come to a close and more institution-building was going on. The first Chinese cartooning heyday came few decades after the US, but this is partly attributable to China being a poorer place with a lot of internal turmoil.

We also see experimentation in cinema. Just as vaudeville actors appeared in early American cinema, a lot of the early screen actors in China were dramatists first. They were playwrights, they were stage actors, and then they would buy a second-hand camera and start a film company with their buddies from the theater world. They were also film-goers, so they were seeing films that had been imported into China from around the world.

The clips I’m showing are slightly longer because I’m assuming people haven’t seen these films. I want to give you a sense of the texture and the narrative flow. As you can see from this still image from Laborer’s Love (1922) (fig. 13), people falling down appealed to audiences in China. This was the first film made by a new film company that was a grassroots, shoe-string organization. The directors both came from the theater world and are considered to be pioneers of the modern Chinese stage and screen. They were very important in Chinese cinema history, and acted in their own films.

Laborer’s Love is the story of a love that risks being thwarted by a father figure, Dr. Zhu, played by co-director Zheng Zhengqiu. One of the two young lovers is Carpenter Zheng, whose background is partially explained in an intertitle. Zheng used to be a carpenter and has now come up north, presumably to Shanghai, and changed trades to become a fruit seller. Early in the film he uses a device to send some fruit as a token of his affection to the doctor’s daughter. And it’s on a wire with a little basket—it goes from one stall to another, over to her. And she sends her handkerchief back to him. So this is one of the ways they court each other. She still needs her father’s permission in order to marry this guy, so traditional morality is at work here, but it gets a comic treatment. The clip below shows how Carpenter Zheng goes about bringing business to his prospective father in-law. Laborer’s Love is a silent film, and the clip is of just the last seven minutes or so.

Rea: Laborer’s Love is only 22 minutes long, but it has a lot going on. You may have seen Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, where the man gets caught in the assembly line. Here in the doctor’s office actually create an assembly line by working together, processing humans, and all the movements are really jerky, like a machine. So we have a common comic interest in how modernity is changing human life and how machines are affecting people. And the special effect in this sequence—the fast-forwarding—is enabled by a machine, the film camera itself.

This is one of three films made by the Star Film Co., but unfortunately the other two no longer exist, so this is the earliest Chinese film that we can see in its entirety. The fact that it was envisioned as part of a comic trilogy, and that more films were made later on, shows that at this time in cinematic history in China comedy sold. And there was a lot interest in experimenting with the camera. We have one still of the second film in the trilogy, The King of Comedy Visits Shanghai (1922) (fig. 14), which had a multinational cast. The guy who played the Little Tramp was not Charlie Chaplin, it was a British resident of Shanghai who had adopted the cane and the hat, the tight-fitting clothes, the mustache and so on and so forth to make a fan-version for the local market. The third film in the trilogy was An Uproar in a Bizarre Theater (1922). I hope that the archive will reveal more of these films hidden away somewhere.

This film was not made just for a Chinese market, but also made with a potential foreign market in mind: it has inter-titles in Chinese and in English. And sometimes the English translation is going for laughs more than the Chinese—“I feel so good I could fly.” That’s not in the Chinese. One of the centerpieces of this film is the trick staircase that turns into a slide. This is an ingenious device, but not an original one, as Xinyu Dong pointed out in a 2008 study. Just one year earlier, Buster Keaton had The Haunted House (fig. 15). I’m going to turn it over to Henry now to show that this motif was very popular and used very widely.

Jenkins: So if we think about what I said so far about vaudeville comedy depending on gags as units that might be combined in a variety of ways, in the ways that Weber and Fields talked about it, we should not be surprised that there are repeated motifs, gags that occur again and again. And indeed, one of my grad students some years back, Andreas Lambada traced many of these tropes back to Italian Commedia dell’arte, which had carefully catalogued a variety of stock gags and comic situations—known as lassi. So I’m going to show a montage in a second from a number of films, a series of versions of the staircase gag. Then we’ll get a bit of Coney Island in that same time period, so you can see how those kinds of gag situations are built into attractions, rides, things that are designed to take tourists and throw them off their feet quite literally. And then we’ll see some doctor gags, which is the second kind of gag theme that we can trace back to Commedia dell’arte in the segment we just saw—all of those contortion jokes involving doctors. Some of these are from silent films, some from sound films, everything I’ve got are from American films that are coming out of the slapstick vaudeville-style tradition.

The first segment from The Electric House (1922) features Buster Keaton, and he plays an electrician in this, not a carpenter. But he’s designed a house in which everything has electric power that allows you to do extraordinary things. Here it’s an escalator not stairs. Another electrician has gotten fired from his job, and he’s getting revenge by manipulating the escalator, much to his confusion.

The second segment is Chaplin’s One A.M. (1916), he’s coming back drunk at night, and he faces a different kind of problem with stairs. One A.M. is more or less a one-man comedy from beginning to end and much of it in the same shot, so we know it’s shot more or less in real time. American slapstick wants to preserve time and space so we recognize the virtuosity of the performer’s body. So One A.M. really is just him interacting with a series of props, and it’s closest to what he’s famous for doing in the British musical, of anything we have preserved of Chaplin’s work.

This is Olsen and Johnson in the film version of Hellzapoppin’ (1941). So again it’s the same stairway gag and here the chorus is thrown straight into hell.

King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928) gives us this footage of Coney Island, during that period; these are things you’d actually experience if you went to Coney Island in the twenties. So John F. Kasson, who wrote Amusing the Million (1978), makes the point that it’s both fun to be the objects being tossed about on these rides, but these were also designed as spaces where you could watch other people riding the rides and being humiliated, thrown about, and forced to fall.

Finally we get two examples of doctor gags – the first from a W.C. Fields short subject, The Dentist (1932), and the second from Palmy Days (1931) featuring Eddie Cantor and Charlotte Greenwood.

So I think you can see that the doctor-dentist gags really become an excuse for contortionism of one sort or another, and very broad physical comedy—that shaking someone’s head back and forth that Weber and Fields talked about. Whereas the staircase becomes about physical dexterity and about engineering feats, both of which work together in silent film comedy in the US to create the worldview that Chaplin is most famous for.

Rea: I get the sense that Cantor really earned his money with the contortionism. A lot of the comedy here seems to be a comedy of expediency: when your escalator’s not working you just slide down the banister. In Laborer’s Love, the opening titles in English say that this carpenter uses the tools of his trade to get what he wants. Whatever your trade, there’s a kind of a professional craftsmen aesthetic at work.

The staircase reappears later in one of the last films made before the communist takeover of 1949: Wanderings of Sanmao the Orphan (1949). This film is in a tragicomic vein, dealing with the pathos of an orphan in the streets of Shanghai. The war from 1937 to 1945 against Japan had created a lot of orphans, so they were a really conspicuous presence. Sanmao (Three-Hairs) is so named because he has three hairs on his head. Out on the streets, he gets involved with street ruffians, and we see some camaraderie between all these starving orphans in the street. Then he gets adopted by a high society family, which throws a party. The parents dress up Sanmao in a nice little suit but he sheds it and helps his friends sneak in the back door. When his adopted mother goes to find out what’s going on she climbs up the staircase and eventually the house is overrun with orphans (fig. 16). We have literally upwardly mobile and downwardly mobile orphans sliding down the banisters. Dad’s going upstairs, and a kind of bedlam aesthetic breaks out.

I only realized when Henry and I were having an exchange in advance of today’s talk that the staircase is a motif that comes back again and again, even in Chinese film, where we don’t have as big of an archive. Unfortunately, the Japanese bombed Shanghai in 1932 and so a lot of early films were destroyed. But some films that do survive we show destructive bedlam for our amusement.

Jenkins: This class conflict is a central building block of American silent film comedy during that same period, ultimately resulting in destructive bedlam. The Battle of the Century (1927) (fig. 17) is Hal Roach’s film with Laurel and Hardy, which results in a hundred-person pie fight. The streets are overflowing with people smashing each other in the face with pies, and it grows out of occupational and class conflicts—upper- and lower-class people getting their frustrations out by slamming pies into each other’s faces. And that same class conflict is there in the Marx Brothers, often played out with Margaret Dumont (1882-1965) as the dowager (fig. 18), the wealthy person against whom the Marx Brothers direct their anarchic energy. The Marx Brothers in various ways are interlopers, disrupters, who often come from street backgrounds: Groucho is a shyster, Chico is an Italian gypsy, Harpo does silent, bodily comedy . . . but they’re disrupting universities, elite parties, ocean liners—in each film they’re going into a space that’s associated with powerful, wealthy people. And they represent the voice of the street, who dismantles that façade, overturns pretensions and deceptions, and shows the true face of power.

Probably the most potent of those clowns from the streets are the Three Stooges: there’s nothing classy at all about the Three Stooges (fig. 19). They do come from this incredibly lumpen proletariat background of broad physical comedy and they’re often situated in settings where they’re either passing themselves off as professionals or they’re moving into an elite social space, and bringing complete destruction where-ever they go. So class politics shapes this kind of comedy every bit in the US as it does in China during that period.

Rea: Another thing I want to point out in Laborer’s Love is the glasses. The film was responding to Harold Lloyd (fig. 20), who for many years in China was more popular than Chaplin. Again, Dong Xinyu has written about this. Lloyd was known for his Lonesome Luke character, and a character known as the Glasses. He had an iconic look: boyish, optimistic, and wearing spectacles that drew attention to the expressiveness of his eyes.

Fig. 20: Harold Lloyd as “the glasses” in a publicity shot, in a Shanghai magazine and in Never Weaken (1921)

We see spectacles in Laborer’s Love as well as in this film Never Weaken (1921), which was made just a year earlier. The plot of Never Weaken features a doctor with a young lady working for him, and a young striver who wants to marry her. But the doctor’s business is bad so the young man has to think of a way to keep her from losing her job. The very first issue of The Motion Picture Review in Shanghai had Harold Lloyd on the cover, and we see Lloyd iconography with Carpenter Zheng as well as with Dr. Zhu—even with the filmmaker himself (fig. 21). A picture of Zheng Zhengqiu shows him wearing the same glasses, so this was a popular look. Chinese literary magazines and fashion magazines carried ads by glasses stores marketing Luoke or “Lloyd-style” glasses.

Jenkins: So the same pattern of imitating Harold Lloyd carried over to Japan. John Dower, who’s a historian of Japanese culture between the wars, points out that by World War II those glasses had become emblematic of the propagandistic images of the Japs. When you see the Japanese image in World War II movies with the thick glasses, it’s actually Japanese attempts to mimic Harold Lloyd to seem modern and Western that are now being turned into a frightening propaganda image that makes the Japanese seem alien to American culture.

Rea: And actually in the 1950s a lot of the anti-Japanese films in China after WWII use exactly that iconography of the Coke-bottle glasses-wearing Japanese.

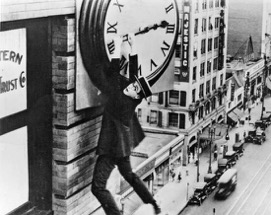

Jenkins: Lloyd represents this movement within slapstick comedy from gags that could be performed on stage to gags that could only have been performed in cinema, ones that require even more elaborate physical spaces. So in Safety Last! (1923), his best film, he climbs three different skyscrapers in order to get the footage for that movie. I live on Broadway and 9th, in the Eastern Columbia Building, and it turns out only two buildings down is one of the skyscrapers Lloyd climbs in Safety Last! (fig. 22).

So here in LA we live surrounded by the settings that these performers used. By the time Harold Lloyd films this particular sequence, he’s already blown three fingers off doing another gag, so he wears a rubber glove on that hand. It’s not enough that he’s climbing the side of an actual skyscraper and hanging on by one hand at various points, but he’s actually only holding on by two fingers on one hand in some of these sequences when we watch it. That sense of just doing the extraordinary in real spaces as a kind of slapstick comedy getting bigger than could ever be done in the theatrical setting is an important part of the appeal of Harold Lloyd around the world.

Rea: And Jackie Chan again is really to credit with re-establishing that connection in modern kung fu comedy. He replicated Lloyd’s stunt exactly—but with more fingers. We talked about trick cinematography with the fast-forward in Laborer’s Love, but this image (fig. 23) is also interesting: Carpenter Zheng is thinking of his lady love and their future together.

The image is a response to and in some ways an extension of trick photography. Back then, you could go to a photos studio in Shanghai or even in second tier cities and buy what was called a “two-mes” photo (er wo tu) or a split-self photo (fenshen xiang) (fig. 24). In the top left is the same woman twice: the photo is double-exposed so she’s dressed as a country bumpkin and a fine lady asking for money from herself. This variant of the genre was called a “self-beseeching photo” (qiuji tu).

These photos circulated in magazines. The editors would go to a studio and all get shots taken of themselves in various poses, like as a strongman holding themselves up. It’s a similar type of play with gadgetry. The man on the bottom is playing chess with himself. You find these trick photos in Europe in the late nineteenth century, when artists and regular consumers would buy this type of novelty image. You even get them being sent around the world as postcards; in China people would frame them on their walls. Some people have written about China’s encounter with modern technology as being one of fear that “There’s a ghost in the machine!” and that photography violated old taboos. “Don’t have your photograph taken, it’ll steal your soul.” This school of thought is confounded by images like this that clearly show people having fun with the technology. It was a type of common amusement, at least among a certain social class, and it worked its way into cinema as well.

Even the deposed last Emperor of China, Puyi, had a photo session taken where he appeared in double (fig. 25). He doesn’t look like he’s having a lot of fun but presumably this was done for amusement. So it went all the way up and down the hierarchy.

This is a postcard (fig. 26) that I found striking for a number of reasons. Partly, I recognize it as a kind of studio portrait that was common in the late 19th and early twentieth century. However, this guy has an excited expression on his face that is like the expressive, over-the-top emoting that you get in films like Laborer’s Love where there’s a lot of showing head-waggling, broad smiles, open mouths, and so on. So even though “Chinaman eating rice” nowadays may seem a little weird, it seems like this guy is in on the joke and is having fun with it. This photo was used for a salad dressing advertisement—that’s the product you see up on the top. But the captions are in three languages, two Western languages on the bottom and then Chinese on the side. And then the handwriting at the bottom is in French, so presumably this was sent overseas. So just like Laborer’s Love was made for an international market, you have a similar type of circulation going on in print.

The next clip is from a 1930s film, and two of the people that we’ll see in it, Han Langen (1909-1982) and Yin Xiucen (1911-1979) (fig. 27), were known as “China’s Laurel and Hardy”—a skinny man, fat man duo. We’ll see clips from a couple of films in which they appear, one from 1934 when the Chinese cinema industry was getting rolling. Some of the comic performance styles will seem quite familiar.

But there’s another comedian and actor appearing in this film, Li Lili (1915-2005) (fig. 28), who was known as the “sweet big sister.” She had a robust physique, was always smiling, a very approachable on-screen persona. . . She’s introduced in this film, Sports Queen (1934), as being a very athletic type. She’s a girl from the countryside, and she arrives in Shanghai by boat. When her family members get off the boat they can’t find her. Why? Because she’s climbed up the smokestack of the ship, which is just like the trees she used to climb back home. So her character introduction is quite striking as someone who’s got a really robust, overt physicality.

When she’s in Shanghai she’s introduced around, and she’s the typical, naive girl coming the big city—will it corrupt her or not? A potential love match is made, featuring another sequence involving a staircase. Young Master Gao is a stiff, kind of mechanical, dandy-ish figure. And when she’s being set up with him, she chases her dog down the staircase at a run, knocking her aunt over, the dog jumps on Young Master Gao, and she jumps into her presumed beau’s arms, completely overwhelming him. We won’t see too much of her comic performance in this next clip but I just want to mention that her expressiveness and her bodily comedy is one of the attractions of this film.

Sports Queen is a really good film if you like to look at women’s legs. But I love that dissolve, where we move from the women’s butts to the guys’ butts. There’s a kind of different type of visual pleasure in watching these guys perform. And there’s really interesting things going on in this film in terms of gender representation, particularly in sequences showcasing Li Lili’s athleticism. In the above clip there’s a dialogue between the Laurel and Hardy characters, where one says, essentially “You’ve got to imitate me and be really fast in doing your work!” I feel like he’s saying you have to be just as athletic as me in waking up, taking a dump, brushing teeth, and so on. I did find a version of this film on YouTube with subtitles but they cut out the “taking the dump,” so somebody censored the scatology in that comic sequence. Han Langen has this little suspenders move, which is quite athletic, and is a type of a visual gag. And then of course they get caught in the doorway when they try to get out. This is a type of performance that would be recognizable to Chinese filmgoers who had seen Laurel and Hardy.

Jenkins: Alright, so in responding to that clip, I pulled two things. The first is a film that features Laurel and Hardy called Hollywood Party (1934) (fig. 29), which is not one of their solo films, they are part of an ensemble. And they’re cast against a woman named Lupe Vélez (1908-1944) who was Latina, a Mexican-born comedian. While silent slapstick in America is often sped up for that comic efficiency he’s talking about, Laurel and Hardy slow things down. There’s kind of a slow, ritualized display of violence and aggression here, where each person carefully takes turns and then reacts to each other. And in this scene, you’ll see it at as a three-way with Lupe Vélez. Hardy is definitely the most powerful figure in this film and it looks like that role is reversed in the segment from Sports Queen. So it’s interesting to see the pairing with a different power dynamic.

So while there’s no taking dumps in this, the look on Oliver Hardy’s face as the egg slides down his body is every bit as scatological, I’d argue. And these same sort of gender wars are represented there.

The second clip I’m going to show is also from Palmy Days, the Eddie Cantor film we saw before. But this features Charlotte Greenwood (1890-1977) (fig. 30), who was one of the top female comedians of the period. One of the things I was happy about with What Made Pistachio Nuts? was that I really dug up a number of these female clowns of the early sound period who had been written out of the history of comedy. I find to the present day, Tina Fey or Amy Schumer or Sarah Silverman are constantly being bombarded with questions about whether women can be funny, and whether they’re breaking new boundaries by being female comedians. But in fact women run through the history of comedy, they just get written out by subsequent generations. They’re left out of these histories of comedy. In this scene, the clown, Charlotte Greenwood, is surrounded by athletic women again, offering the kinds of voyeuristic pleasures we saw in Sports Queen.

That sequence was one of the first that Busby Berkeley (1895-1976) did for Hollywood. Berkeley followed in the footsteps of Joseph Urban (1872-1933) who had staged similar numbers in the Ziegfeld Follies (active 1907-1936), which had a tradition of “glorifying the American girl.” So what we see here is a kind of showing off, getting women as undressed as we possibly can within the censorship standards of the era. The “Bend Down Sister” bit has obvious motivations and this is a pre-Production Code film.

What’s interesting to me about Sports Queen is that it looks like the sexy, cute girl and the comic girl can be combined in that film. Whereas here we see the female comedians of the thirties tend to be failed examples of femininity—they’re all too tall, too fat, or too ugly to be the romantic lead or erotic eye candy. Their comedy comes out of trying to be attractive, thinking of themselves as attractive, doing very physical things, but not being the glorified girl. Charlotte Greenwood is famous for her high kicks, and she has the same amount of physical dexterity and can do stunts as well as any of the male comedians of the period. She’s often presented as a woman seeking desire and pleasure on her own terms, which is what makes them still feel liberated in some ways—she would go into towns ahead of the films and challenge men to foot races and usually beat them. So she was trying to prove her physicality, but her tall, lankiness is usually read as gawky and not particularly feminine.

This is Winnie Lightner (1899-1971) (fig. 31), another woman I wrote about in What Made Pistachio Nuts? She did a lot of stuff around burlesque, and she has a song about “Look me over here, look me over there”— she’s calling attention to her body but at the same time according to Hollywood standards she’s not supposed to be particularly attractive.

Lupe Vélez does get to be sexually attractive and even glamorous (fig. 32). But in another way she’s crossing a line because she’s Mexican. She’s cast as the Mexican spitfire and in most of her films, her hot temper makes her dangerous. The press of the period called her a “hot tamale,” compared her to “paprika”—“so spicy! It tastes really good but it burns your tongue, so you’ve gotta watch out!” The play on her ethnicity is central to her character. Her contemporary Delores Del Rio was a more light-skinned Mexican woman of the same vintage who Hollywood did cast as romantic lead. But Lupe is more working-class, darker-skinned, and she gets cast as a more comic lead even though she clearly has a lot of sexual attractiveness by the standards of the time.

Rea: Li Lili was one of those actresses who could be both comedic and sexy at the same time and the sequences in Sports Queen do kind of set her off from the two Laurel and Hardy clowns—they have separate sequences that don’t integrate too much. And in Sports Queen a lot of the narrative does end up with some sort of paternalistic male figure coming in and taming this unrestrained woman so that she won’t get too full of herself. So there is that rather conservative element there.

But you have other productions by Chinese studios at the time such as Lianhua, which was one of the big studios at the time. They would make a sampler film called the Lianhua Symphony (1937), where you would have a bunch of different genres of films, maybe four different genres. All these shorts were put together to provide variety and to showcase certain performers. In the slapstick section of this symphony it’s not enough to have just one Hardy, you have two Hardys—one Laurel and two Hardys interacting with each other (fig. 33).

I wanted to show a couple of clips from one last film to raise the question of how vaudeville and virtuoso comic or athletic performance changed in the People’s Republic of China. It was a very different regime, hostile to a lot of frivolity and urbanity. The Communists had gotten their support from the countryside and were very suspicious of a lot of these institutions like amusement halls. So we have this same comic duo returning in a film called Unfinished Comedies (1957). Unfinished Comedies is a fascinating film; it was banned pretty much immediately upon its release in 1957; I don’t think it was screened publicly until the 1980s when the print was rediscovered. It has three films within a film, and it’s very autobiographical in some ways.

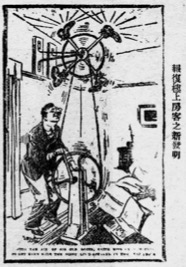

The filmmaker, Lü Ban, had been unhappy with the state of comedy in the first years of the People’s Republic. He felt like there were a lot of restrictions on directors and so he made a film featuring a film director at the Changchun Film Studio, where Lü Ban himself actually worked. Director Li has made several films, including one bringing back together this duo, who have been apart for ten years or so. His nemesis is Comrade Bludgeon, the in-house film censor (fig. 34). So they have a screening of three films Director Li has made, and then we get Comrade Bludgeon’s negative reaction to all three of them. I want to start by showing a clip from the first of the three films-within-a-film. Within this we have a manager who comes and has an interaction with his subordinate. So let’s roll it and see what happens.

So manager Hogg is off to the fat farm. But we have this story that begins and then all of a sudden stops and we’re looking in the “ha-ha” mirror and showing off our bodies. You can forget yourself looking in one of these mirrors. You can forget you’re a stern manager, shouting at your subordinates. It’s also an image that would take viewers back—if they had been able to see it. They enjoy this laugh together, and it’s all good fun. But if you recognized these characters, you’d recognize not just this type of fun bodily performance—Han Langen’s grimaces, Yin Xiucen’s rotund body doing interesting movements—you would also recognize the object itself.

The “ha-ha” mirror (fig. 35), or the funhouse mirror, was associated with a type of urban institution that you found in Shanghai, in Singapore, and in other cities like Hong Kong. These amusement halls offered a new type of approach to entertainment that was very much about variety and choose your own adventures. You could go into the Great World (fig. 36) or the New World and at the entrance you would see multiple “ha-ha” mirrors.

Many of them were imported from Holland, I discovered, or from Japan. In the clip we just saw Han Langen’s character says, “It’s really hard to get these things; I had to send someone all the way to Shanghai.” And the manager says, “Well, go get some more! If they don’t have them in Shanghai, go down to Guangzhou, go further afield. . .” But there’s this paucity of comic delight because we’re not producing them anymore, and they’re hard to get. So this is a film that is some ways about the continuity and rupture in this comic tradition, symbolized by the performers and this object themselves. So you see these mirrors in China and also . . .

Jenkins: Watching this clip, I thought about what roles mirrors play in American slapstick comedy and thought about a sequence from Duck Soup (1933) involving the Marx Brothers (fig. 37). This gag plays upon the family resemblance between these performers. Not unlike Hogg, Groucho is a powerful official—the president of Freedonia—whereas the other two brothers are spies hired off the streets to infiltrate positions of power.

Rea: Later in Unfinished Comedies, in the first of three comedies within the comedy, the ha-ha mirror reappears. When Manager Hogg went off to the fat farm, he had his pocket picked on the train by a thief. Then the thief fell out of the train and died, and his head was smashed, but they recovered the body, along with Manager Hogg’s wallet, so the tone is quite different when he returns.

To me that’s a really stark framing (fig. 38). I wanted to close with that, partly because it seems to me like a comic filmmaker’s response to those who would try to bury comedy prematurely.

So we have the return of the ha-ha mirror, which really does create a ghost. And the rhetoric of ghosts also had particular resonance in China at this moment because of a film, previously a stage play, called The White Haired Girl, set back in the “bad old days.” A landlord had raped this woman, and she had to hide in the mountains where she suffered from vitamin deficiency and her hair turned white. She would run down to the temple at night to steal food, so the people all thought that she was ghost. But when the Communist army arrived they helped her become human again. So the slogan was, “The old society turned humans into ghosts, but the new society is going to turn ghosts back into humans.” But here we have these comedians being turned into ghosts, putatively, so all that, “I’m not dead, I’m not dead! I’m alive! I’m a real person!” seems like a real cri de cœur of a comic filmmaker arguing for comedy. And really making it stark in the presentations of these two icons of the old society’s comic culture being killed off and trying to fight back. But again, this film was banned. A lot intellectuals underwent their own trials by fire in this period.

Jenkins: I thought I would close by just observing what happens to the strand of American film comedy, both in terms of thematics (how is it pulled into the orbit of propaganda as the 1930s gives way to the 1940s) and formally (the pleasure of a performance that stops the story dead gives way more and more to forced linear narratives in which the comedians get expelled from the center of their own movies). So here we see three films of the 1930s (fig. 39), Wheeler and Woolsey’s Diplomaniacs (1933), W.C. Field’s Million Dollar Legs (1932), and the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup (1933), all of which feature comedians in political roles as heads of imaginary nations. So, as presidents go, they are treated as buffoons, fools, knuckleheads—in short, total Trumps.

By the 1940s (fig. 40), they are specifically cast in relation to the Nazis, the Fascists in Italy. So here we see Chaplin’s Great Dictator (1940). The Three Stooges did a series of films where they play the leaders of Germany and Italy, and we see the Disney film Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943). All three of these films harness slapstick to take down dictators and rallying support for the troops. But each in their own way is now marginal: The Three Stooges are making shorts for Columbia, the smallest and weakest of the studios in the Hollywood system, Chaplin has now been forced to move from silent comedy to sound as his power has diminished, and Disney is doing this as an animated short. There are almost none of what I would call the anarchistic comedies coming out by the 1940s. That style of comedy has just been pushed out of the Hollywood system under pressure from the twin goals of classical narrative and propaganda which constrained the free play of laughter that’s part of the 1920s, 1930s slapstick.

Rea: I would say in closing that the “ancient art of falling down” is still alive in China. I don’t know if I could say it’s alive and well, because there is indeed, very heavy censorship and a lot of things are taboo, off limits, and not negotiable. But online you do get a lot of bricolage videos, you do get things that are put up and maybe taken down later, but they do exist. And you do have some mainstream filmmakers like Jiang Wen (b. 1963) doing very edgy stuff in films like Devils on the Doorstep (2000), which turns Japanese war criminals into buffoons and comic figures in a way that’s extremely subversive and works against mainstream discourses. So comedy is still possible and the talent is still there, but it remains to be seen how things will develop in the future.