By Qi Wang

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright September 2019)

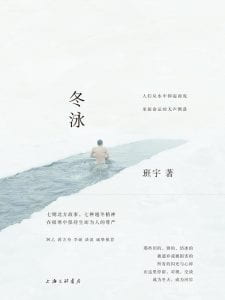

In my wandering around in the cinematic and literary world of East Asia, I have come upon many echoes and parallels among cultural imaginations across national borders. One such example is that of the comparable pulses I find in the films of South Korean maverick director Hong Sang-soo (b. 1960) and the stories of a much younger Chinese writer Ban Yu (班宇, b. 1986), even though their works deal with very different social subjects. Hong made his debut film, The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (1996), when Ban was still an elementary school kid in Shenyang. Hong weaves a cinema out of numerous rounds of wandering and drinking of frustrated Korean artists and intellectuals; Ban crafts a literary world in which laid-off workers in northeast China and their families try and fail to adapt to life in the reform era. Over the years, Hong’s arthouse corpus has continued to spin tales around waiting and wandering, creating thinking time between stops. This rejection of story efficiency and plot mechanism in which every step is not necessarily a preparation for the next step tends to characterize the art of a number of East Asian filmmakers and storytellers, a propensity that is worth pondering in terms of alternative paths for development. Different rhythms of life, usually appearing slower and more contemplative, seem sorely needed in the contemporary world. The young Chinese author Ban Yu (b. 1986), who started his writing career as a music critic, is a recent example of an East Asian cultural imagination that continues and refreshes this particular inclination for narrative realism. This current essay discusses Ban’s first literary collection, Winter Swim (冬泳), and presents the author as a brilliant thinker and stylist.[1] His prose features an alternative rhythm that is made manifest through kinesthetic arrangements such as waiting, wandering, and swimming. The last, in particular, is the author’s unique invention and characterizes the inner life of some Chinese in northeast Asia from the 1980s to the present.

Prosaic Realism, Poetic Flight

Ban Yu’s seven tales, presented in this debut collection of 2018, capture the fates and pains of workers and their families in northeast China through a brilliant combination of prosaic realism and poetic transcendence. Here is my attempt to summarize Ban’s story world in one imaginary scene:

A man walks along a lusterless winter street lined with few attractions; the sky is colorless. His gait is sometimes fast, sometimes slow. Except for the road in front of him, the ambiguous space seems practically free of any coordinates. Now he finds the road has turned into a river, his body already doing the strokes as if he had been swimming the whole time. Like the road before, this river lacks identity and drifts in a space that is equally emptied of references. The swim then dissolves into a flight in a space that is as dull and featureless as the road and the river before it. Suddenly, the man sees an image that summarizes all that there is and has been in his walking, swimming, and flight. This image burns. In the darkness that follows, the man imagines that far above or in the distance, there might or might not be stars.

Ban’s fiction demonstrates the following impressive characteristics: a layered and angled narration that at first appears straightforward and even flat. Often narrating in first-person flashbacks and frequently assuming the point of view of a child who observes the adults around him, the stories do not shy away from taking up the position of those very adults—often fathers and uncles who are the central characters—to provide information only available to the latter. The temporal register, although we know the setting is in the 1980s and 1990s, feels present and matter-of-fact due to a mostly chronological and unemotional presentation of daily lives and commonplace behaviors. Characters do errands, buy or eat food, wait for jobs, cook for lovers and in-laws, and sleep. They are up and about despite a general sense of disorientation and despair. Their efforts of living a simple life often fail, and sometimes become downright criminal.

A peculiar dynamic between biographical comprehensiveness and historical inconclusiveness ripples through Ban Yu’s portraits and tales of northeast China. He writes about the fates of workers in the city of Shenyang, which is also the subject of a famous documentary film, Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (铁西区, dir. Wang Bing, 2003). Once the darlings of Mao-era socialism, in the reform era heavy industry factory workers lost practically overnight all their social privilege and economic security. In Ban’s world, the unfolding of a character’s life tends to spell its disintegration, a fate that is cut short and sealed off despite the character’s efforts to adapt and change for the better. For instance, in “Panjin Leopard” (盘锦豹子), Uncle Sun Xuting lives his life: from dating, to marriage, to fatherhood, to unemployment, to survival, to divorce, to more survival, to almost losing his home at the end of the story. In “Roads in Midair” (空中道路), Li Chengjie, another uncle figure and also a worker, dies and thus completes the story of his life well before the narration begins. The narrators, a father and a son, chat and reminisce about an important occasion when the father and Li began a friendship as co-workers. The sense of completeness is ironic and poignant when it comes to an individual life, because very few of Ban’s characters have any hope for a better future. They are simply too ill-equipped to continue and succeed in the new era. Their life prospects are foreshortened and rear-ended when the big change—the disintegration and marketization of the state industries—happens. The flow of change is constant, overwhelming, and inconclusive.

On a larger scale and beyond the unidirectional failure of workers to adapt, there is a double move between past and present in the world of Ban Yu. On the one hand, the past seems to be taking place in real time toward the present/future, thanks to the chronological, matter-of-fact flow of prose filled with verbs, actions, and behaviors. Ban’s characters are quite busy, actively living in the present, even though little seems to be accomplished in the end. On the other hand, much like what Raymond Carver does in “Chef’s House,” a sad story narrated in first person about one brief, good summer in the life of a struggling couple, quotation marks are removed from all of Ban Yu’s dialogues so that they appear mute and remote like reminiscences frozen in the past.[2] From this temporal dynamic that conflates past and present, the author then waxes poetic and takes flight in daydream or drunken reverie, in which the suffocating low-pressure world of history and reality might inhale some fresh air in the company of the stars.

Deathly Wells

The story “Gun Grave” (枪墓) revolves around the first-person narration of an unnamed “I,” who is a writer currently collaborating with Xiao Wen, an editor who starts a profit-driven writing studio. Xiao plans to use her contacts to arrange book deals with publishers and hire professional writers to fulfill those deals. As the new studio is taking shape (and very soon falls apart), “I” tries to start a romance with a woman named Liu Liu, who, like “I,” is also a provincial migrant from the northeast to Beijing. Not always encouraged in his attempts at intimacies, “I” spends time with Liu Liu reading a story he has written and saved on his mobile phone. The story-within-a-story is about a certain Sun family, how the father Sun Shaojun tries a number of occupations after quitting his factory job, how he meets his second wife, Wu Hong, and the couple struggles and fails together, and how the son Sun Cheng loves reading and works at the Xinhua Bookstore. Although never explicated as such, the character Sun Cheng in the embedded story is a thinly disguised alter ego of “I” in the story proper.

The title “Gun Grave” refers to the most dire episode in the life of the father figure, Sun Shaojun. After trying his hands at selling shoes, gambling, running a noodle shop, and selling banned fireworks, Sun becomes part of an armed robbery team that eventually gets arrested for murder and sentenced to death. Sun had insisted that he never owned a gun, but after his death, his son discovers a gun in the box containing his grandfather’s ashes. In Ban’s signature style of chronological, first-person narration, we come to the end of both storylines at once: When “I” finishes telling the story-within-a-story, the writing studio falls apart, the editor disappears without paying the royalties for “my” work, and Liu Liu and “I” leave Beijing. “I,” however, decides to part with Liu Liu on the journey, leaving without saying goodbye when she is sound asleep on the bus.

In this chronological flow of ruthless time and wretched life, man and woman, father and son, all seem so busy and hardworking yet hapless and unlucky. The few uplifting moments of warmth and tenderness come from the narrator’s time spent with Liu Liu, even though she often seems underwhelmed by him. Besides the parallel flow of two streams of narrative—the current life of “I” and the reading of the story of the Suns—“Gun Grave” takes hold in a reader’s mind because of a few minor images perpendicular to that narrational flow: abandoned wells and frozen lakes in which bodies and figures are stuck ( 260-261, 292-293, 300). The first well appears in a minor story embedded in “Gun Grave”: “I” has come to know Liu because she liked a story that “I” wrote and posted online, a piece about a taxi driver who vanishes until his car is found thousands of miles away in Inner Mongolia, his corpse dumped in an abandoned well (260-261). Liu herself brings up the second well, which is also lodged in hearsay: on a home visit to Qiqihar, the second largest city in Heilongjiang, she learns that a local driver has vanished and the police have searched the entire city before locating his corpse in an abandoned well. This death, at least according to the police report, appears to be a suicide (293).

Besides these two deathly wells, there are at least five more vanishings in “Gun Grave.” Two more drivers disappear in the armed robberies for which Sun Shaojun is sentenced to death, despite his pleading not guilty and denying collaboration in the crimes. Sun’s wife, Wu Hong, also vanishes one day without a trace. The son, Sun Cheng, as the fictional counterpart of the narrator “I,” encounters a man on the deserted ground of an abandoned villa construction site; Sun and his family used to live in the area. The man he runs into is the former supervisor of the failed real estate project, and he is also in search of the past. When the construction was going on, the man’s wife and daughter visited him on the worksite but vanished on their way to a bus stop. Once every few years, the man returns to this place because he still dreams about his wife and child; in his dream, “they have not gone anywhere and remain stuck at this place as if being held down at the bottom of a frozen lake” (300).

Frozen Waters

In Ban’s stories, figures abused by time disappear into abandoned wells and frozen waters. Bodies of the innocent and hardworking are dumped in the wells; the struggling spirits who witness or experience such a sorry existence swim in canals and lakes but remain under the frozen surfaces. In “Gun Grave,” as the primary “reader” of the story-within-a-story told by “I,” Liu Liu claims that she finds the son figure Sun Cheng familiar and has even dreamed of him once. The two of them seem stuck at the bottom of a frozen lake, she says: “we want to get onto the bank but do not know in which direction we should swim, the lake’s surface is frozen, the sun sheds light on it, golden rays bounce off it, but inside the lake it is still very chilly, and there is no exit anywhere” (292-293).

Ban’s prose has a peculiar rhythm that works off a contrast between qualities of flowing and solidity, busyness and frozenness. In story after story, he packs small actions into matter-of-fact descriptions. Narrators and characters alike are busy making a living while thinking—through reminiscing and storytelling—in little pockets inserted into a banal daily life. The sentences are long yet clean; they are composed of short phrases, each relating a behavior, an action, an observation, or a sensation that comes from external elements acting on the body. Here is one example, in which I deliberately keep the run-on structure for the sake of literal fidelity to the original Chinese:

I panic, make a turn further down, bike like crazy to another path, that yelling is close upon me the whole time, becomes more pressing, I dare not turn around, but can feel he is only a few meters away, pressing closer with each step, a flock of birds takes flight from the ground, I pass through them, as if I were one of them, flying ahead, I pedal hard, dare not relax for one bit, pass the building complexes, turn onto a main road, gradually slow down, turn around to look, nobody follows behind, I finally relax to breathe (84).[3]

我心里发慌,便在前面拐了个弯,向着另一条小路疯狂地骑去,那喊声始终紧随其后,更加急促,我没敢回头,但能感觉到他离我也就几米的距离,正在步步逼近,地上的一群鸟飞起来,我在它们中间穿行而过,仿佛也成为它们之中的一员,朝着前方飞去,我奋力蹬车,丝毫不敢放松,经过楼群,转到一条主干道,逐渐放缓,回头一看,后面已经无人跟随,这才松一口气。

In another sentence, Ban enacts the strokes and sensations of swimming from one end of a pool to the other. In yet another, his prose performs a dive from a diving platform, providing concurrent observations that are smaller but also complete acts in their own right. For instance, “violent sounds of wind fill up my ears, my arms enter the water, work up waves” (90-91). At the end of “Winter Swim,” within one single sentence, the narrator reminisces about a fatal encounter with Sui Fei’s father and reenacts in prose a brawl between the two, which in the next sentence entails the death of the old man (107-108). These are verbal equivalents of long takes in filmmaking, examples of which are numerous in the films of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Jia Zhangke, Bi Gan, and South Korea’s Hong Sang-soo and Lee Chang-dong, although the exact kinesthetic dynamic in each director’s long takes—the duration, frequency, and speed of action and movement—is different and worthy of a more detailed discussion than can be provided here.

Moving like a walker or swimmer, Ban’s prose enacts movement through space while offering significant impressions and sensations about the changing environs. One short clause could be one step, followed by another, and yet another. It seems that Ban’s protagonists are constantly on the move; they have little time to pause, but neither is their pace all that rushed or disorderly. The prose’s steady rhythm goes hand in hand with the presentation of concrete actions and crisp images, assuring a fine balance between objective description and emotional resonance. Ban’s peculiar mixture of first-person narration and third-person voice also contributes to that balancing, an effect that tends to accompany reminiscences of a special, postsocialist kind. In independent Chinese cinema, for example, we see similar hybrid exercises of objectivity and subjectivity in the work of Jia Zhangke.[4]

When romance happens, the lovers also tend to take walks together as if they were a pair of fellow travelers. In “Gun Grave,” the delicate but definite confirmation of a heartfelt connection between “I” and Liu Liu takes a form similar to swimming in a cold river: “wind blew over, we walked even faster and more lightly, like we were threading through water, the air bobbed and wobbled, the scenery drifted and floated, this kind of evening I had not had for a long time” (286). The story-within-a-story that “I” has been sharing with Liu Liu ends on a bus that the two take to “go further north.” Then “I” vanishes out of her life: “I muster all my spirit, continue forward, I know, before everyone wakes up, there is a long way to go, I can only finish it on my own” (302).

The narrator turns himself into a mobile and searching figure who is perhaps in pursuit of all those who have disappeared without a trace. None of those vanished figures—the taxi drivers or the women—come back alive. Having labored for years and ending up incarcerated and sentenced on account of armed robberies and murders, the father figure Sun Shaojun seems to be swallowed into a black hole of existence in which he tries, but fails repeatedly, to make a decent living by legal means. What destroys his belief in making a life out of honest labor is the abuse he suffers at the hands of an authority figure: the vice-director of a detention center. Sun’s wife, Wu Hong, is arrested and sent there for illegal sale of fireworks. When Sun goes to pick her up, the vice-director, a drunk and abusive man, slaps him in the face before signing the release document. He does that because Sun, having just spent all the money he had on the fines related to Wu’s case, is unable to pay a bribe. What is more, it turns out that Wu has suffered rapes and other abuses at the detention center, a place filled with all sorts of people who have been pushed onto unimaginable paths in life (283-285). As for how Sun Shaojun ends up being part of the armed robberies, that turn of events remains vague and unexplained in the story. He only leaves behind a gun in a box of cremated ashes, which is solid evidence of violence as well as a silent symbol of repressed anger. But “I” as well as Sun Cheng, the young writer/narrator/son figure, chooses not to use the gun for killing. Instead, he symbolically descends into the wells and beneath the frozen waters in search of the abused and the lost. Such an archaeological gesture is comparable to the literary attempt of Haruki Murakami, the Japanese writer who repeatedly goes into wells and pits in search of answers and remedies for the emotional traumas in Japanese society at its current stage of advanced capitalism.[5] Along with his narrating characters, the author Ban Yu resorts to storytelling, joining the vanished and making the voices that were once hushed underwater heard through resounding silence, a paradox that is powerfully communicated through his careful removal of quotation marks from all the dialogues.

The story “Winter Swim” contains a very elaborate image of frozen waters: a canal where past, present, and even future come together in the protagonist’s pursuit of love and redemption. Presented in chronological order through first-person narration, “Winter Swim” begins with “my” date with Sui Fei, “me” a thirty-something worker, Sui a divorced woman with a quirkiness that “I” finds genuinely appealing. As the relationship unfolds, “I” learns about Sui’s past: her father was found drowned in a frozen canal, an incident that she believes to be a murder committed by her ex-husband, with whom she has a daughter. As the man holds custody of the child and still harasses Sui, even trying to extort “I” for money, “I” beats him up, leaving his body, wounded and unconscious, out on a freezing winter night. After that violent fight, “I” returns to see Sui and on the next day, the two pick up Sui’s daughter from the kindergarten. They spend a day together “like a typical family of three,” hanging out in a shopping center and eating hotpot in a restaurant (104-106). The mother and daughter want to burn joss paper for Sui’s deceased father by the canal in which the old man has drowned. While they are busy with that, “I” wanders away, takes off his clothes, and enters the canal for another winter swim, an exercise “I” regularly does in the story. At this point, without warning, the author’s matter-of-fact narration takes a heartrending, fantastic turn and leads us into a landscape whose coordinates can be anywhere in or between reality, hallucination, and death. Ban’s prose flows with few stops, easing our way from a winter swim to a memory that unsettles all that has happened before. It turns out that “I” might have been the inadvertent murderer of Sui’s father. The two once got into a brawl that went out of control. The current winter swim might be a self-punishing suicide, as “I” continues to stay under water, reminiscing and fantasizing about a past that feels present. “I” sees himself submerged in the canal with the drowned old man. When “I” reemerges from the water, Sui and daughter are no longer there, and “I” seems to be in a barren land that might symbolize the afterlife. The final paragraph of “Winter Swim” is equivalent to a run-on prose poem:

I, stark naked, emerge above water, look toward the road by which I came, I do not see Sui Fei or her daughter, the clouds are thin, the sky destitute and dim, I walk all the way back, do not see any trees, ashes, firelight, or galaxies, on the bank there is only me, nobody else, wind has blown everything away and apart, even on the ground that has been burnt, there is no trace of any kind, but that does not matter either, I think, like taking a walk in the afternoon, I keep on walking, walking a little more, as long as we are all on the bank, we will meet again (108).

我赤裸着身体,浮出水面,望向来路,并没有看见隋菲和她的女儿,云层稀薄,天空贫乏而黯淡,我一路走回去,没有看见树、灰烬、火光与星系,岸上除我之外,再无他人,风将一切吹散,甚至在那些燃烧过的地面上,也找不到任何痕迹,不过这也不要紧,我想,像是一场午后的散步,我往前走一走,再走一走,只要我们都在岸边,总会再次遇见。

Whether “I” reemerges alive from the canal is unclear; he might be dead.[6] “Winter Swim” feels like a slow descent into a frozen river, passing through scenes from daily life on the way: cooking, eating, unsuccessful dates, unexciting sex, and meeting with figures whose lives seem equally boring and unpromising. One barely notices any change in the narrative temperature until the chilling revelation at the end.

In the chronological flow of the first-person narration, “I” carries out with due diligence work, romance, and family life with his mother. “I” lives and loves, humble, earnest, and not without dignity: he does not force his feelings onto Sui, letting her take the lead while trying to help her (such as taking photographs of her daughter at her request). The only moments in the story in which “I” feels alone tend to take place in or near water: swimming in a pool lane; biking next to or swimming in the canal. These are the places that command the poetic ruminations of the narrator in which reality and fantasy blend, and these are also the sites where “I” is confronted with guilt and isolation (83-84, 107-108, 91-92). For example, on the way to see Sui’s young child at the kindergarten, “I” is chased along the canal by a mysterious crazy man in a green paramilitary uniform who seems to know the crime “I” committed long ago; the crime—the murder of Sui’s father—is not revealed until the end when “I” returns to the canal, this time taking a plunge into memory and possibly death. Comparable to the abandoned wells in “Gun Grave” that hold dark secrets of murder and trauma, the frozen canal in “Winter Swim” serves as a disposal site of memories from a troubling past. In the past, there is more than one death: the canal produces dead bodies at a regular rate over the years (96). Apart from these, the canal is also where a child, possibly a friend of “I,” has drowned; “I” feels guilty for failing to save him (107). Such haunting moments of fixation and reflection are like dark whirlpools churning into the matter-of-fact flow of daily life. They turn a terse realist narrative into a resounding lyrical poem centered on pain and melancholy.

To Imagine, To Transcend

The deathly wells and frozen waters are a kind of “chronotope,” in the terminology of M. M. Bakhtin, a spatial metaphor that summarizes and visualizes particular and meaningful relations between time and space in a narrative.[7] In the fictional world of Ban Yu, these peculiar wells and waters hold traces and sediments of all the abused, wasted, and forgotten lives. At the same time, they also serve as channels that motivate movement and action, such as swimming, remembering, and storytelling on the part of the many first-person narrators, which amounts to a sort of historical and mnemonic archaeology for contemporary China.

For its part, the story “Roads in Midair” imagines a spatial equivalent of the wells and waters high up in the air: an imaginary transportation network operated by cranes becomes the site where a worker places a desirable but impossible future. The story begins with a memory of the first-person narrator: in 1998 when he was in fifth grade, his father, Ban Lixin, spoke to him about Uncle Li Chengjie, an acquaintance of the family who had been dead for some years. The story then alternates between first- and third-person narrations, the latter devoted to the father’s flashbacks about his friendship with Uncle Li, his co-worker. The two men once traveled together on a vacation and were stuck in a suspended cable car in the mountains because of a system malfunction. Trying to dispel their fear, Uncle Li shares with Ban Lixin his love of literature. He recounts Doctor Zhivago, the 1957 novel by Boris Pasternak, and explains his own fantasy about an alternative mode—a “more cubic” one, in his words—of urban development, which had just started gearing up in China (128-130). Inspired by his own labor specialty as a crane operator in the factory, Uncle Li’s essential idea is to make the best use of midair space by creating a sort of rail-free transportation system operated with cranes that, in his futuristic imagination, are equipped with state-of-the-art foldable arms. In Li’s conception, passengers go to a crane station, where a crane picks them up, carries them through air, and drops them at a desired destination. To solve the potential conflict with the increasing number of skyscrapers, the crane stations could be conveniently built into the sides of tall buildings, where they might also serve to replace elevators. As the two young workers imagine this together, their immobile cable car starts moving and they pass through the crisis safe and sound. The two men then carry on with their respective lives, working at the factory, raising a family, and getting laid off in the reform era.

Uncle Li’s imagination of a transportation system in midair is poignant because it asserts an optimistic and unrealizable vision of his own livelihood—operating a crane—that he would soon lose. The factory on which he relies for a living, along with an entire system of socialist economy and social welfare, will close to create space for new models and reforms. The northeast region has famously lagged behind China’s overall growth in prosperity.[8] Li’s almighty crane system, with its confident verticality, like the many skyscrapers that have been erected all over China, is a fantasy about the sustainable importance of the old working class; he imagines that he can sit comfortably in and operate those cranes while the world moves at his or his fellow workers’ command. These fantastic cranes and their trajectories of alternative development echo the frozen waters in Ban Yu’s other stories where figures navigate and swim, futilely active in a strange state of suspension, of mobility in stasis. The cable car suspended in midair turns out to be a spatial metaphor for the fate of the two workers trapped in it.

“Roads in Midair” does not recount the period between that cable car moment and Li’s death. Instead, it ends with two isolated moments from the earlier lives of the two worker-father figures: Ban Lixin almost gets in a drunken fight but holds back his frustration and anger out of consideration for his two-month-old son (namely, the narrator “I”); Uncle Li Chengjie is waiting outside the delivery room, tired and worried, and falls into a deep sleep. “At that moment, neither man realized what a relaxed, long night that was, they were empty-handed, suddenly free and light, walking in a dream, walking in the sky, not even having to carry the weight of their shadows” (135). In those flitting moments, they pause and rest, while their life is on the brink of entering a new era where there will be family and responsibility as well as the challenges of reform and unemployment. The circumstances of Uncle Li’s life and death are not explained, but one can conjecture by looking at the trajectory of Sun Shaojun in “Gun Grave,” discussed above, or the other worker-father figures in “Panjin Leopard” and “Worker Village” (工人村).

Also told in chronological and largely first-person narration, “Panjin Leopard” is named as such because the protagonist Sun Xuting’s nickname is “Leopard” and he comes from Panjin, a small city in Liaoning. The story follows Sun, the husband of “my” father’s sister, through the ups and downs—mostly downs—of his life as a worker, a husband, and a father. Sun works in a state-owned printing factory that soon begins reforms in order to compete and survive in the new market economy. A dedicated worker, Sun makes an important contribution to the successful installation and operation of a “new” technology—an expensive printing machine that the factory has recently bought without properly researching it (14-16). However, Sun’s wife, the narrator’s aunt, runs away one day for a more comfortable life, leaving behind her husband and a young son. The distressed Sun loses an arm when it gets jammed in the very machine he once worked so hard to install. Less useful as a worker now, Sun shifts to the marketing sector of the factory and finds a way to increase profits by printing cover cases for pirated VCDs and DVDs. The illegal operation is discovered, and the factory gives Sun up to the police in order to protect its interests. Jobless, Sun starts selling welfare lottery tickets to make a living; all that remains in his life is his apartment—the only financial remnant of his factory years—and a son. One day, his long-estranged wife returns; the two are still legally married, and she tries to sell his apartment to pay off her gambling debts.

“Panjin Leopard” ends with a striking moment of Sun holding up a rusted knife and trying to attack the two anonymous men who come to inspect his home as part of the sale (43-44). Sun’s tortured life, at this point, comes to a standstill and congeals in a powerful image that lives up to his mysterious nickname “Leopard.” Half-naked and with the circular imprints of a physical therapist’s cupping visible on his body, he jumps at the two strangers. This is a man who has worked hard, tried to be a nice boyfriend, a caring husband, a responsible father, and a self-reliant unemployed man, who finally snaps under the unbearable and unfair stress. His nickname “Leopard,” mentioned early in the story but with no explanation, has created a tiny, suggestive space—something like a breathing hole—in the story’s impressively objective presentation of one ordinary, though difficult, life. With everything else explained, including the wife’s abrupt disappearance, this empty nickname—so important that it serves as the story title—remains to be excavated and substantiated until the end, when Sun is seen leaping into the air, temporarily transforming himself into a human leopard:

Sun Xudong saw his father hold a rusted kitchen knife in hand, burst out a cry, come in and take a look, you motherfuckers, and with extreme agility he leapt into the air, becoming born again from the winds that cracked… (44)

The power of Ban Yu’s literary talent does not stop there. He develops sophisticated contradictions through tale after tale in which workers experience both harshness and tenderness, wretchedness and dignity. “Panjin Leopard” does not conclude with the frustrated and violent outburst but with tears of a very sad but elevating kind. Ms. Xu, Sun Xuting’s gentle masseuse girlfriend, is emotional, her crying “very shy and modest, yet also resilient and bright,” a crying that the son Sun Xudong finds extremely “beautiful” and that also brings tears to his eyes (44-45). Similarly, another story in the collection, “Solemn Chill” (肃杀), recounts a fouled friendship between two jobless fathers—one ending up swindling the other of his life-depending motorcycle—and concludes with a bright and refreshing, though ambiguous, image of snow falling on a girl’s fake eyelashes. The image quivers in the solemn chill that permeates this story of helplessness and despair. The narrator of “Solemn Chill” repeatedly runs into the son of Mr. Xiao (who has cheated the narrator’s father and run away) and his girlfriend. On one snowy day, he finds the girl walking alone:

[She] had on an old sweater no longer fashionable and was shivering, the sequins on her sweater flashing a drab glimmer; her hand was holding tight at the loose opening of the neck, her lips zipped tight, her eyes squinting, every step appeared hard, suddenly a cold breeze blew by, big snowflakes fell off the tree and landed on the length of her fake eyelashes, at that moment, I found her so extremely beautiful. (70-71)

To summarize, alongside the chronological flow of life delivered by a matter-of-fact prose, the stories in Winter Swim contain a remarkable chronotopic system formed by deathly wells, frozen waters, and imaginary paths in midair that are where memories and pains settle and stay. Although having a phantomic quality because of their representation of the abused and suppressed, these spatial tropes persist with a compelling solidity: the wells are immobile, the cranes are steely, the northern winter canals and lakes are frozen. They are then lifted, temporarily and wishfully, through eruptions of lyricism and poetry when the author’s unsentimental narration takes sudden flights in fantasy and brings up stars and galaxies and “those million things floating in midair” that, alas, cannot be of any assistance to those down on the ground, deep in the wells, and “at the bottom of the river” (44, 289). Within this fictional universe where hopes are folded over onto themselves and where people move in a forward stasis under a wintry sky, our first-person-speaking narrators join the flow in the freeze. Ban’s tales are deeply empathetic elegies of the generation whose lives, first as socialism’s working class and then as postsocialism’s unemployed, bear intimate and resounding testimonies to contemporary Chinese history. As the young figures who observe, remember, and record, Ban Yu and his fictional stand-ins are walkers and swimmers who work hard to keep on moving despite the freezing despair.

Qi Wang

School of Literature, Media, and Communication

Georgia Institute of Technology

Notes:

[1] Ban Yu 班宇, Winter Swim (冬泳) (Shanghai: Sanlian shudian, 2018). Translations in this essay are all mine. Page numbers refer to this edition.

[2] Raymond Carver, Cathedral: Stories (New York: Vintage Contemporaries, c1981, 1989), 27-33. With Ban Yu, the only exceptions in which dialogues appear in quotation marks are two segments in the story titled “Workers’ Village” (工人村), see, Ban, Winter Swim, 214-246.

[3] My translation suspends conventions in English grammar in order to follow exactly the same composition of Ban Yu’s sentence. Each clause in the translation matches one clause in the original text.

[4] For a discussion of Jia Zhangke’s mixing of objectivity with memory and contemplation, see Qi Wang, Memory, Subjectivity and Independent Chinese Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 93-103. That book argues that an outstanding motivation of the independent cinema between 1990 and 2010 is a historical consciousness about the complex legacies of socialism in the reform era. The fiction of Ban Yu, who was born as late as in 1986 (compared to the generation of filmmakers born in the 1960s and early 1970s whom I studied in that book), is the newest addition to that ongoing reflection on the impact of reform and change.

[5] Two novels by Haruki Murakami that contain outstanding wells and well-like structures are: The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, translated by Jay Rubin (New York: Vintage International, 1997); Killing Commendatore, translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018).

[6] In the second to last paragraph, “I” reminisces about the brawl with Sui’s father in the previous year, through which he “pulls me into the dark [which] was in the depth of cliffs … we discovered at almost the same time that it was an extremely tiring darkness, exuding an air that felt safe and cozy, like endless warm currents, we were deep in it, there were no lights or any light at all, in the layered embraces of water grass we both fell sound asleep” (108).

[7] Bakhtin, M. M., “Forms of Time and of The Chronotope in the Novel: Notes toward a Historical Poetics,” in his The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas, c1981, 2006), 84-258.

[8] One highly illuminating study of contemporary cultural productions and memories of northeast China is written by Liu Yan 刘岩, History/Memory/Production—A Cultural Study of the Northeast Old Industrial Bases (历史/记忆/生产――东北老工业基地文化研究) (Beijing: Zhongguo yanshi, 2016).