By Li Chi

Translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang

Originally published by Foreign Languages Press (Beijing, 1964)

Reprinted online by the MCLC Resource Center, 2003.

PART THREE

Landlord Tsui’s Return

Fine weather may to foul give place:

A scout arrived with anxious face.

“Whites!”—panting hard he could not stay—

“The cruel Whites are on their way!”

They hurried to cut off the Whites;

Each able-bodied peasant fights.

“No time for fond farewells, Wang Kuei,

The signal’s gone! To arms! Away!”

When word reached Dead Goat Bay, ’twas night;

The Whites arrived with morning light.

Each soldier’s face was black and grim,

As if back pay was owed to him.

They searched the place from door to door,

And asked: “Who’s joined the rebel corps?

And who was given cows and sheep?

And who got property to keep?”

One had a cave, so they discovered;

In no time was the place uncovered.

The landlord’s gate was tall and wide,

With two hemp ropes the man was tied.

With switch of nettle and of thorn,

His naked back was whipped and torn.

That White commander, hateful beast,

He clenched his fists, his lips he creased:

“No water’s drawn when wells are dry;

Nor can the poor be rich—why try?

It’s fated that you should be poor;

Yet still some change you struggle for.

The Reds are but a broken reed,

A pretty crew to trust, indeed!”

Then ropes to bind, and knives to hack,

His ill-won gains Tsui soon got back.

After the jackals led the way,

The wolf came back to Dead Goat Bay.

Long gown, short jacket, walking-stick

The sight of him would make you sick.

From one house to the next he’d go:

“It’s vain to envy me, you know.

The men of old revolted too,

It’s quite a commonplace ado.

It’s like the Heav’nly Dog on high,

Who eats the moon up in the sky.[1]

But soon the moon appears once more,

And shines as brightly as before.

Fair fortune makes the rich her friends,

As soon an upstart’s triumph ends.

Who is your rightful ruler, pray?

Tsui rules the roast in Dead Goat Bay!”

A swine turns always to its swill;

For Hsiang-hsiang Tsui was lusting still.

Her dad was for a soldier sent,

Then to her home the landlord went.

With yellow teeth bared in a leer:

“Well, girl,” he said. “Just look who’s here!

You can’t hold out against me now;

Old scores shall be wiped out, I vow.

Poor widow, how I pity you! .’,

Your husband has skedaddled too;

So don’t be stubborn; come with me;

Good food, good clothes—how gay you’ll be!”

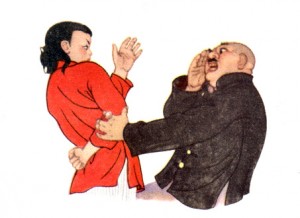

Then Hsiang-hsiang, angry, in dismay,

Just bit her lip. What could she say?

And thinking silence meant consent,

He grabbed at her with vile intent.

He meant this time to have his way,

When none was there to say him nay;

And, seizing her with all his might,

He tried to ravish her outright.

Trembling with rage she turned to fly,

Rushed to the door and gave a cry;

But with a grin he barred the way.

“Women are fools,” said Landlord Tsui.

Once more he started to give chase,

But Hsiang-hsiang spat right in his face;

She kicked at him and clawed his head,

She scratched his face till both cheeks bled.

The neighbours, at the turmoil, came;

The landlord had to leave for shame.

But at the door the villain paused:

“Just see what trouble you have caused.

I tell you plain, mark what I say,

Like it or not, you’ll yet give way!”

The Handkerchief

The heart of Landlord Tsui was deepest black,

And Hsiang-hsiang’s father never more came back.

The old bird dead, her mate, the young bird, flown,

How could the poor girl manage on her own?

To join the partisans was her one thought,

But by the cunning landlord she was caught.

First rice he’d send, then flour to her would cart,

Tsui thought in this way he could win her heart.

This one and that were sent to her by Tsui,

They came to seek her several times a day,

The fierce to threaten, others to persuade,

But true still to her husband Hsiang-hsiang stayed.

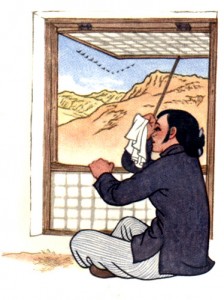

Each day she cried: her cheeks were wet so often

That even hearts of stone would have to soften.

A newly-wedded bride ought not to cry;

But Hsiang-hsiang’s handkerchief was never dry.

Her handkerchief, full eighteen inches wide,

Was soaked with tears again as soon as dried.

Outside her window there was rising ground,

And just beyond the fort the sandhills wound;

But though some hills were high, some hills were low,

To find her lover Hsiang-hsiang could not go.

A sturdy elm tree grew the house near by,

Although its roots were thick, it was not high;

And every morning she would ask the tree:

“Oh, tell me, elm, where can my husband be?”

While watching the wild geese that southward fly,

She heard an echo to her mournful cry.

“Wild geese, folk say, will oft a message take.

Please take my lover one, for pity’s sake!

Say: Trees were sprouting when you went away,

Though leaves have fallen, still from home you stay.

If any horse won’t pull, the whip is heard:

And if you can’t come home, just send a word!

Two mighty piles of bricks with stones between:

Ah, no one knows the troubles I have seen.

As clouds by gusts of wind are quickly scattered,

Our married life was by another shattered.

What seed that grows is rounder than a pea?

What other couple is as sad as we?

Smoother is wheat than any other grain:

What other couple knows our grief and pain?

Now, sick with longing, from my food I turn;

The fire within my heart makes both lips burn.

Rice grows in shady places, wheat in sun,

And as I think of you, my eyes o’errun.

I take my rice bowl, yearning still for you;

Down fall my salt tears in the rice bowl too.

Too lonely in the dusk my lamp to light,

I long for you till late into the night;

Nor can I close my eyes the whole night through,

But on my bed a portrait trace of you.

I call on you to save me every day;

My days are numbered, love, if you delay.

But should I die, one thing I swear to you:

Short stirrups and long reins for horses high:

My spirit will be with you if I die.”

Now Aunty Liu was a kind-hearted dame,

To put fresh heart into the bride she came.

With words of comfort oftentimes came she:

“Now cheer up, dearie, and pay heed to me!

Our partisans will all come back one day,

And then we’ll settle every score with Tsui.

We’ll catch the beast alive, his arms we’ll tie;

And all White traitors will be killed or fly.”

One grain of buckwheat has got ridges three:

Poor Hsiang-hsiang was as wretched as could be.

A spell of drought brings death to every farm:

And Hsiang-hsiang, thin and sallow, lost her charm.

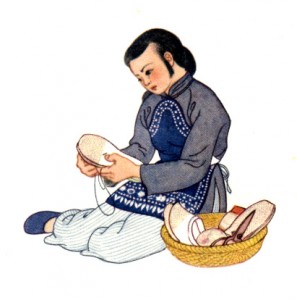

But ill and wasting, shoes of cloth she made,

Gave them with tears to Aunty Liu, and prayed:

“Please keep these slippers, Aunty, in my stead;

And give them to Wang Kuei when I am dead.

Oh, tell my husband when he takes this pair,

They are the last shoes made by me he’ll wear.”

The Lovers Reunited

Quite mad with rage was Landlord Tsui:

“Confound the wench! She must obey!”

No wolf or tiger fierce as he,

Poor Hsiang-hsiang, trapped, could not get free.

A rich feast in his hall was spread,

Before New Year they were to wed.

All was got ready at top speed,

Only officers came to the feed.

Each private drew some extra pay,

And drank and gambled it away.

But Hsiang-hsiang felt her heart would break,

Her tears poured down for Wang Kuei’s sake.

Trousers of green, silk coat of red,

They made her wear, as if to wed.

She wept and cried, she cursed the day:

“You’d marry your mother, you devil Tsui!

Some day, I swear, I’ll find a knife,

And then, you dog, I’ll have your life!”

But Tsui, quite deaf to all she said,

Was puffing opium on his bed.

Replete, to join his guests he went;

Like well-fed dogs, they were content.

I drink to you, you drink to me,

They swilled in hoggish jollity.

The guests expressed congratulations,

As if they were Tsui’s close relations.

Then in a smile his face was creased:

“Forgive what’s lacking in this feast.

To you my warmest thanks are due:

I should have failed if not for you.

I ought to call my concubine,

And order her to pour you wine;

But like a fool she sobs away;

She’ll drink with you another day.

Some tastes there’s no accounting for,

She scorns the rich and likes the poor.

However hard young Wang Kuei tries,

Arms can’t compare with thighs in size!

This match was fixed by Heaven’s decree;

How could she get away from me?

Ewe lambs are for the rich man’s fold,

There’s nothing for the poor to hold.

The truth is, when all’s said and done,

From east—not west—must rise the sun!”

Guzzling away they left no guard;

Guerrillas came into the yard.

With shouts of “Kill!” and rifle crack,

Our partisans were fighting back,

Each man with trusty horse and gun,

A finer unit was there none.

Then armed with rifle, spear or sword,

Shot-gun or musket, in they poured.

Not one White soldier cared to fight,

Like lambs they all gave in outright.

Torches were lit, their radiance gleamed;

In the rejoicing neighbours streamed.

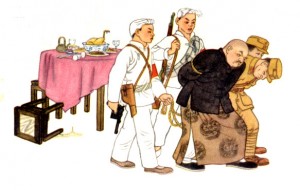

The drunken feasters were appalled,

Under the bed the landlord crawled.

The captain fled, the sergeants, caught

And roped, into the yard were brought.

The landlord’s pudgy face dripped sweat;

Now they would make him pay his debt!

The captain tried to scale the wall,

But he was captured after all.

And Hsiang-hsiang laughed to hear guns crack:

“Our partisans are back! They’re back!”

Great happiness gives strength, it’s said,

She jumped up quickly off the bed,

Flashed through the door, so eager she.

“My lover—where, oh, where is he?”

With leave to take his bride away,

Into the courtyard came Wang Kuei.

All round was bright with torches’ glare,

But he could not see Hsiang-hsiang there.

Only far off a bride was seen,

In jacket red and trousers green.

Head a horse home, he knows the way;

And Hsiang-hsiang recognized Wang Kuei.

“That same towel round his head!” cried she.

“That is my husband—none but he!”

Now the two meet, and hand clasps hand;

Enraptured, speechless, they both stand.

Their hearts are full, but they are dumb;

They long to speak, but no words come.

But at long last hear Wang Kuei say:

“To revolution, love, we owe this day. . . .”

1. According to Chinese mythology, the eclipse of the moon is caused by the “Heavenly Dog,” which takes the moon for a meat ball.