Source: China Digital Times (11/6/23)

Translation: “Don’t Expect Kindness and Humanity from Totalitarian Dictators”

By Cindy Carter

A fiery-eyed Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor (259-210 B.C.E.), who was famed for his book-burning and brutality.

A brief, fiery essay excoriating totalitarianism has been censored on WeChat, and appears to have precipitated the closure of a Jiangxi-based current- and legal-affairs blog. First posted on the public WeChat account 法制江西 (Fǎzhì Jiāngxī, “Jiangxi Legal”), the ten-paragraph essay—interspersed with photographs of contemporary strongmen and vivid illustrations of the brutal emperors of old—extolled the virtues of liberal democracy and argued for the “inevitable demise” of authoritarian systems. Some aspects of the essay echo, intentionally or not, the vision for a “Beautiful China” of rights lawyer Xu Zhiyong, who was sentenced in May to 14 years in prison for subversion. Soon after the essay disappeared from WeChat, the “Jiangxi Legal” public account announced, without any explanation, that it had been suspended and would cease posting updates. The account’s public profile described it as “a general news column, under the auspices of a legal-affairs Party media outlet, offering in-depth analysis and commentary on trending topics in the news,” and described the content as “a global perspective, a Chinese point of view, explaining current events and discussing all manner of things.”

On Chinese social media, there is routine censorship of content praising so-called “western values” such as democracy, rule of law, human rights, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech. In recent years, there has also been an uptick in the censorship of content and works referring to failed or despotic emperors and other figures from antiquity, particularly if that content is viewed as being obliquely critical of Xi Jinping’s rule. In October, a reprint of the historical biography “The Chongzhen Emperor: Diligent Ruler of a Failed Dynasty” was pulled from bookstore shelves and online booksellers due to a cover redesign and promotional quotes that seemed to implicitly criticize Xi Jinping. (One blurb on the book’s wrapping read: “The diligent ruler of a failed dynasty, Chongzhen’s repeated mistakes were the result of his own ineptitude. His ‘diligent’ efforts hastened the nation’s destruction.”) The name “Chongzhen” and related topics were later search-blocked on Weibo, with searches only showing results from verified users. Continue reading

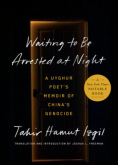

Uyghur poet’s memoir recalls the Xinjiang administration’s retrospective hunt for unPC content in textbooks once commissioned, edited and published by the state:

Uyghur poet’s memoir recalls the Xinjiang administration’s retrospective hunt for unPC content in textbooks once commissioned, edited and published by the state: