By Christopher Lupke

Reviewed by Frederik H. Green

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright September, 2016)

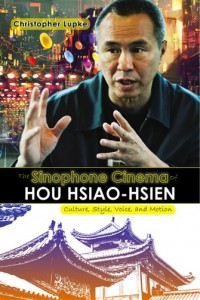

Christopher Lupke, The Sinophone Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien: Culture, Style, Voice, and Motion Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2016. 387pp. ISBN: 9781604979138 Hardback: $124.99

Early in chapter 1 of his engaging new book The Sinophone Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien: Culture, Style, Voice, and Motion, Christopher Lupke recounts his first encounter with the world-renowned director’s work. After watching Hou’s A Time to Live and a Time to Die (1985) as a graduate student in the late 1980s, Lupke recalls being so impressed by “the stationary camera and long-take sequence,” “the measured space; the focus on individual, seemingly inconsequential conflict,” “the cacophony of contending voices” that he had a hunch that this director might just have “slammed shut the door on all the cornball comedies, Cold War historical romances, and lachrymose melodramas” that had hitherto dominated the cinema scene in Taiwan (6). Lupke’s account made me recall my own “Hou Hsiao-hsien moment” of about a decade later (triggered, as it happens, by the same movie). Somewhat bewildered by the movie’s technical complexity and nebulous plot, I was nevertheless mesmerized and left the screening craving more. This sense of awed bewilderment at Hou’s masterful cinematic technique and subdued storytelling is something I would experience again and again after each subsequent encounter with his work, including his most recent The Assassin (2015). In plain, jargon-free language replete with astute insights garnered from decades of scholarly engagement with the films of Hou Hsiao-hsien and Taiwanese cinematic and literary culture, Lupke sets out to lift the veil of the technical finesse and structural ambiguity that enshrouds much of Hou’s oeuvre and frequently frustrates film spectators. In this endeavor alone, Lupke succeeds brilliantly.

Lupke’s study, which spans the entirety of Hou’s career as a director, is also a “thick description” of the complex contextual minutiae and historical elements surrounding and informing his films. As the title The Sinophone Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien suggests, Lupke does not primarily see Hou as a Taiwanese filmmaker—even if Hou, maybe more than any other Taiwanese filmmaker, has become synonymous with the New Taiwan Cinema (台灣新電影) that began to flourish in the 1980s. Instead, Lupke suggests that Hou’s work, which linguistically and culturally “dwells in contested terrain” (3), needs to be read within a theoretical framework that considers both the complex political and historical environment against which Hou’s work has to be read as well as the linguistic range found in his films, from standard Mandarin to the local Taiwanese Hoklo, from Hakka to Cantonese and Shanghainese, Japanese, French, and smatterings of English. As such, the Sinophone, a concept first suggested by Shu-mei Shih to describe, among other things, literary and cinematic production in the “polyphonic and multilingual” Sinitic-language communities and cultures (mainly) outside the borders of mainland China (Shih 2013: 10passim), seems highly appropriate.[1] Yet even the broadly inclusive concept of the Sinophone, Lupke hastens to add, cannot entirely accommodate Hou’s work, both because the “idiosyncratic innovator in the realm of global postmodern theater” (3) has long been claimed by an international audience of cinema aficionados that reveres him as a filmmaker whose art speaks the universal language of the art house cinema, but also because in his later oeuvre, Hou actually transgresses the linguistic confines of the Sinophone to produce films in which the narrative language is Japanese and French, respectively.

In order to do justice to the scope of Hou’s work, both in its transnational and trans-linguistic orientation as well as its technical sophistication and cultural complexity, Lupke has chosen to simultaneously focus on the set of interpretive categories that comprise the book’s subtitle: culture, style, voice, and motion. These four terms constitute the basis for the analytical focus of each of the book’s six chapters, with the exception of chapter 1, which provides a comprehensive and highly informative overview of Hou’s work and of Taiwan’s socio-historical development in the second half of the twentieth century and the first decade and a half of the twenty-first. In the opening chapter Lupke divides Hou’s career into five discernible topical (and largely chronological) phases: a partially commercial phase in the 1970s; a biographical phase in the 1980s that also saw Hou play a pivotal role in the emergence of the New Taiwan Cinema; a political phase in the late 1980s and 1990s in which the colonial and KMT legacies as well as Taiwan’s modernization are scrutinized; an existentialist phase shortly before and after the turn of the century in which Hou also branched out into transcultural and translingual territory; and a historical phase in the 2000s in which Hou began to explore China’s literary and cultural past. Of particular interest in this opening chapter is Lupke’s discussion of the three films that constitute Hou’s debut as a director. These early films were produced at a time when “the combined state-run studios and commercial film industry still held sway” (8). They thus display many of the characteristics associated with Taiwanese postwar “healthy realism” cinema (健康寫實電影), such as the prominence of popular music, use of light humor, and the resolution of relationship or social problems. Although Hou has since distanced himself from these early films, Lupke convincingly argues that they mark a vital stage in Hou’s evolution as a creator and reflect some of the artistic concerns that would become hallmarks of Hou’s later oeuvre, such as conflicts between modernization and rural communities in Cute Girl (1980), tromp l’oeil and alienation techniques in Cheerful Wind (1981), and a semi-documentary quality in Green, Green Grass of Home (1982).

Each subsequent chapter explores roughly in chronological order one of the five creative phases outlined in Chapter 1 by engaging in case studies that analyze one or more representative movies. These case studies at the same time engage with one or more of the interpretive categories from the book’s subtitle. For example, chapter 2, which is entitled “Zhu Tianwen and the Sotto Voce of Gendered Expression” and which focuses mainly on Summer at Grandpa’s (1984), explores the degree to which Hou has permitted the female voice of Zhu Tianwen, his most important collaborator and co-author of almost all of his screenplays, to both subtlety subvert patriarchal ideology in postwar Taiwan and to add to the structural complexity of his cinema. Hou achieves this, Lupke argues, largely by “moving back and forth not merely between male and female characters but between experiences and viewpoints that are gender specific” (71), thus challenging what some critics have identified as Hou’s gender bias and his reluctance to lend female characters the same narrative prominence as male ones, especially in his earlier movies. In this chapter, Lupke not only demonstrates his astute familiarity with Hou Hsiao-hsien scholarship, which he critically engages with throughout the study, but also reveals his intense familiarity with lesser known yet highly insightful details about Hou’s relationship with his collaborators Zhu Tianwen and Wu Nianzhen.

In Chapter 3, entitled “Comparing Hou Hsiao-hsien and Ozu Yasujirō,” Lupke further expands the scope of the study by reading Hou’s work in relation to the films of the venerated Japanese director with whom (as is often noted) Hou at times shares a certain topical and stylistic affinity. In treating Ozu’s iconic Tokyo Story (1953) alongside Hou’s A Time to Live and a Time to Die, Lupke is less interested in whether the former has exerted an artistic influence over the latter. Instead, his goal is to “set the directors up together in a sort of dialogue,” thereby illuminating how Hou’s movie speaks to Ozu’s and how they “interrelate, how the cross fertilization of theme and in some ways of technique illuminates not just the understanding of these two important East Asian filmmakers, but the understanding of East Asian culture in general” (79). Central to Lupke’s exploration of culture in this chapter is the concept of filiality and/as a particular East Asian notion of subjectivity—namely, one that is relational in structure and exists in contrast to Western individualism (84-85). Lupke convincingly illustrates how both directors’ films manifest “the crisis of filiality in post-war East Asian society” (105) precipitated by modernity and modernization and reflect “the emergence of a new individual subjectivity in an increasingly commodified and transnational East Asian society” (107).

While Chapter 3 explores the question of how to render cultural crisis on screen, Chapter 4, entitled “The Muted Interstices of Testimony,” explores how political crises can be negotiated cinematically and how selective memory can become the fabric of memory itself. By drawing on Anton Kaes’ theoretical work on expropriation and post-war German cinema that showed how certain filmmakers selected, narrativized, and thereby came to “give shape to the random material of history,”[2] Lupke in this chapter focuses on A City of Sadness (1989), the movie that gained Hou international recognition after winning a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival that year. By way of five close readings of key scenes from the movie, Lupke illustrates how Hou inscribes the historical events that are the bases for A City of Sadness into his own lexicon of film technique and how his idiosyncratic technique and production decisions ultimately challenge any attempt at apprehending the unvarnished historical truth about Taiwan’s painful transition from Japanese colony to KMT-ruled Republic of China.

While the preceding three chapters each focus on one film, Chapters 5 and 6 address multiple movies, which are discussed under a common thematic concern. In Chapter 5, entitled “Time and Teleology in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Films of Quest and Disillusionment,” Lupke discusses Dust in the Wind (1986), Goodbye South, Goodbye (1997), Millennium Mambo (2001), Café Lumière (2004), and Flight of the Red Balloon (2007) under the shared theme of what he jokingly describes as “treading water” (156), or, more precisely, the oftentimes futile struggles of Hou’s protagonists and their efforts at overcoming their circumstances, a predicament Lupke then describes as “stasis within motion, a consciousness of the passage of time, and a teleology that ultimately is unraveled by larger social forces” (156). Lupke begins this chapter by quoting Hou Hsiao-hsien, who himself speaks of a sense of “longing for the outside” as a source for his own restlessness (154), before chronicling, through a series of highly engaging and refreshing case studies of aptly-chosen representative scenes from each movie, the respective struggles, hopes, and disappointments of Hou’s protagonists. For example, by reading Goodbye South, Goodbye against a number of gangster films, including Breathless (1961) directed by Jean-Luc Godard (one of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s most important influences), Lupke shows that Hou is at once indebted to Godard and, through the de-glamorizing of his anti-hero gangster-protagonists and the celebration of their mediocrity, provides his own take on the genre. Later in the chapter, Lupke calls Hou “a cinematic anthropologist for urban youth angst” whose increasingly transnational protagonists—Café Lumière is set in Tokyo and Flight of the Red Balloon in Paris—all share a desire to break away from their mundane existence as they experience the futility of modern life in general (179). In his discussion of Café Lumière, which was commissioned by Ozu’s production company and conceptualized as an homage to Ozu, Lupke once more returns to the changing notions of filiality discussed in Chapter 3 and suggests that in the postindustrial environment of Tokyo, the disintegration of filial ties at times leads to an “unmoored existence [that] can be seen as both liberating and frightening” (187). There is a sober yet reassuring quality to Lupke’s conclusion of Hou’s cinematic endeavor as expressed in the films discussed in this chapter—namely, that humans are driven by an existential notion to “seek meaning in a teleological endpoint only to find it in the ordinary bits and pieces of life they encounter along the way” (192).

Chapter 6 turns to Hou’s period adaptations and cinematic explorations of themes from traditional Chinese literature. Entitled “What is Said and Left Unsaid in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Period Adaptations,” Lupke focuses first on Hou’s Flowers of Shanghai (1998), an adaptation of the late-Qing novel of the same name, before discussing last year’s The Assassin, Hou’s adaption of a Tang-dynasty chuanqi. While scholarship on Flowers of Shanghai has mostly focused on the visual splendor of the movie, Lupke instead directs our attention to the importance of dialogue, even though—or especially because—there is so little of it in the film. Lupke compellingly illustrates that it is by examining “what is said, how it is said, when things are said, and what is left unsaid” that Hou’s idiosyncratic cinematic deployment of dialogue brings to life not only fin-de-siècle Shanghai, but also brings to the screen a small sliver of the literary universe of Eileen Chang, the influential mid-century Shanghai writer whose Mandarin translation of the original novel, which was written partly in the Wu dialect, had made the work accessible to a wider audience (211, 214). In his subsequent discussion of The Assassin, Lupke then shows how in making important changes to the original narratives, Hou “carves out a character who is truly modern” (218). In his final analysis, Lupke once more insists on Hou’s preference for aesthetic and interpretational ambiguity when he decries attempts by critics at reading The Assassin as straightforward political allegory of contemporary cross-straits relations or Hou’s own identity quest.

Lupke’s study ends somewhat abruptly, without a formal conclusion. Instead, the final chapter consists of translations of four interviews and dialogues with Hou, Zhu Tianwen, and Xie Haimeng, Zhu’s niece who co-wrote the script for The Assassin, thus adding to the wealth of resources and insights already included in this most comprehensive study of Hou Hsiao-hsien and his cinema to date.

Throughout the book, there is some repetition of biographical information and summaries of movies, but this might only be noticeable if the book is read in its entirety in one sitting. If, however, individual chapters are consulted for teaching or research, the book’s occasional repetitiveness becomes a strength, as each chapter can be taken as a standalone essay without sacrificing some of the general contextual information found in other chapters. Some of the screenshots (provided at the end of each chapter) are very dark, but Cambria Press needs to be applauded for agreeing to include so many of them, as well as a comprehensive Chinese character glossary and a complete and detailed Hou Hsiao-hsien feature-length filmography.

While Lupke discusses at length the many influences on Hou, from Shen Congwen and Huang Chunming to Jean-Luc Godard, this reviewer would have been interested in learning more about the influence Hou has in turn exerted over a younger generation of Taiwanese filmmakers. Can Taiwan’s new auteur-director Chang Tsuolin, whose A Time in Quchi (2013) Taiwanese film critics have interpreted as an homage to Hou’s early masterpiece Summer At Grandpa’s, be placed into a similar creative dialogue with Hou as Lupke convincingly does for Hou and Ozu in Chapter 3? Raising such questions is, of course, a merit in itself, and while Lupke’s study provides us with an abundance of insights and a wealth of information, it also will stimulate students and scholars to take their own studies of Hou’s cinematic aesthetics into new directions. Hou’s career is, of course, far from over. Considering that at age 85, Jean-Luc Godard, is still working on new films, we can expect that Hou Hsiao-hsien, at age 69, has some of his best years as a director still ahead of him. Within in a couple decades, then, there will arise the need for a sequel to The Sinophone Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien. Christopher Lupke would be the man for the job.

Frederik H. Green

San Francisco State University

[1] “Introduction: What Is Sinophone Studies?” Shu-mei Shih. In Sinophone Studies: A Critical Reader. Shih, Shu-mei, Chien-hsin Tsai, and Brian Bernards, Eds. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013. Print. 1-16. See also Shih’s Visuality and Identity: Sinophone Articulations across the Pacific. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

[2] Kaes, Anton. New Cinema from Hitler to Heimat: The Return of History as Film. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.