Source: PRI (7/2/18)

Chinese political cartoonist Rebel Pepper finds more artistic freedom in the US

By Isaac Stone Fish

Listen to the story.

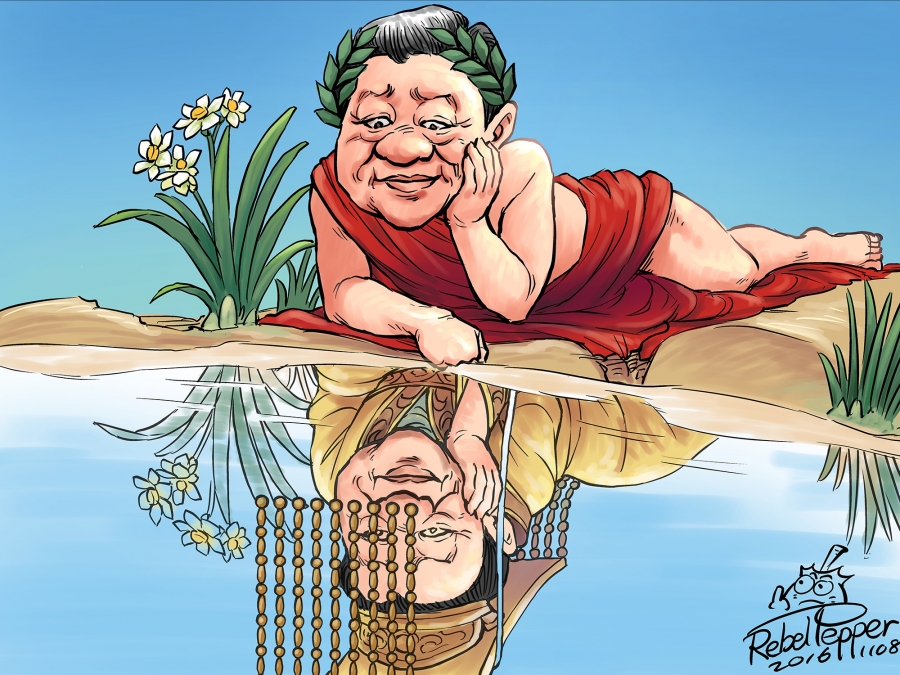

Rebel Pepper drew this cartoon in response to the news that Xi Jinping would abolish term limits for his chairmanship, potentially paving the way for him to stay on as dictator-for-life. Credit: Courtesy Rebel Pepper

What does it mean to live in the United States instead of China?

For China’s most prominent political cartoonist, Rebel Pepper, a dissident with a gentle smile and a wicked brush, it’s the difference between life as a wild pig and a domesticated one.

Kept pigs “think they live a carefree life because people feed them. But one day, they will be slaughtered,” Rebel, whose real name is Wang Liming, said in a May interview in Washington, DC, where he now lives.

Moving to the United States, Rebel feels like he has escaped from the “prison” of China — a prison of both repression and complacence.

Rebel, who had spent a night in detention in October 2013 in China, and who might have faced a long prison sentence for trumped-up charges of “subversion” had he remained in the country, had a prison obsession. He read a “huge amount” of prison memoirs, he told me in 2015.

But that was then. Afterward, he said, “I found myself in a free country,” he said. The adjustment hasn’t been easy.

“I’m starting all over, and I had to find work, and overcome language and cultural barriers,” Rebel, 45, said.

He showed me a photo of his 9-month-old son, Beiye.

“As a first-generation immigrant, I want to make the soil richer,” Rebel said. “My kid will grow up in a free world without fear and will be thinking like an ordinary American. I envy him very much.”

I first met Rebel in May 2015 in Tokyo, where he was living in exile from Beijing, barely earning a living as a cartoonist for Japanese papers. He spoke little Japanese. He had fled China roughly a year earlier, but he was still having nightmares that Chinese security agents would arrest him for his subversive and trenchant political cartoons, many of which satirized the ruling Chinese Communist Party. He formerly had close to one million followers on China’s top microblogging accounts, but the companies deleted his profile; Alibaba closed the lucrative online store he ran on its company Taobao, the world’s largest e-commerce website.

Tokyo was not home.

In an article I wrote about Rebel for Foreign Policy Magazine, I described the fear he felt: “Having left China for Japan, Rebel had thought this his nightmares would end. But they only grew more absurd, more crazed, more intense.” After a devastating nightmare in June 2015, he tweeted the surprise he felt that “special operatives would still murder me in my dreams.” He added, “words can’t describe the helplessness I felt,” and he added an emoticon with tears gushing from its eyes.

Parts of the last few years have been difficult, Rebel told me in May 2018.

“But then I toughened up,” he said. “I got my complete freedom of expression. I no longer need to self-censor myself.”

Rebel’s cartoons have evolved as he has moved from Beijing to Tokyo, where he spent three years in exile, then to Washington, DC, where he moved in May 2017.

Many of his cartoons skewer the power grab of Chinese chairman Xi Jinping who, since taking office in 2012, has rolled back freedoms and accumulated titles and authority. In December 2013, three years after Rebel started drawing political cartoons, Xi visited a dumpling shop in Beijing. State media and millions of netizens applauded Xi for commiserating with commoners. In a cartoon entitled “From Now On,” Rebel drew a sesame bun, a fried dough stick, and a cup of soy milk — common Chinese breakfast foods — bowing down to a dumpling. The message, though communicated subtly, was a clear warning against Xi’s growing authoritarianism.

As Rebel moved overseas, his cartoons grew more direct, but no less forceful. In November 2016, one month after the Communist Party awarded Xi the symbolically significant title “core leader,” Rebel drew Xi as the mythical Greek beauty Narcissus, gazing at his reflection in the water and wishing himself emperor.

Xi Jinping is depicted as Narcissus, who is imagining himself as emperor while gazing at his reflection. Credit: Courtesy Rebel Pepper

In February 2018, news broke that the then 64-year-old Xi would abolish term limits for his chairmanship, potentially paving the way for him to stay on as dictator-for-life. By this point, Rebel had moved to the United States, where he works as a political cartoonist for the US government-funded Radio Free Asia in Washington. Rebel responded to the news with an image of Xi in a pink bathrobe and bunny slippers sitting on the edge of what looks like a bed. Xi gives himself a facial as he prepares to lay next to the body of Mao Zedong in his crystal coffin. It’s the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong, the founder of modern China and the man responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of his countrymen.

“I am quite fond of” this cartoon, Rebel said, in his sweet and mild-mannered way, more Clark Kent than Superman. “It looked hilarious.”

When I asked about his recent work, Rebel cited one that particularly pleased him. In late May, as trade tensions increased, Rebel drew a cartoon entitled “US-China Trade Chess Championship,” which featured the two leaders hunched over a chessboard — Xi playing Chinese chess, and Trump playing international chess. Perhaps Rebel sees himself on both sides of the board, peering over his pieces and trying to comprehend the other perspective.

Rebel Pepper drew this cartoon in late May, as trade tensions increased between the US and China. Credit: Courtesy Rebel Pepper

Dissidents are stubborn people. Some fight because of a nearly unquenchable thirst for justice. Some fight because of egotism — their sometimes misguided sense that they can improve the system they oppose. And some do it from an unyielding need to communicate. “I couldn’t resist the impulse to express myself,” he said.