Source: NY Review of Books (1/26/16)

China: Surviving the Camps

By Zha Jianying

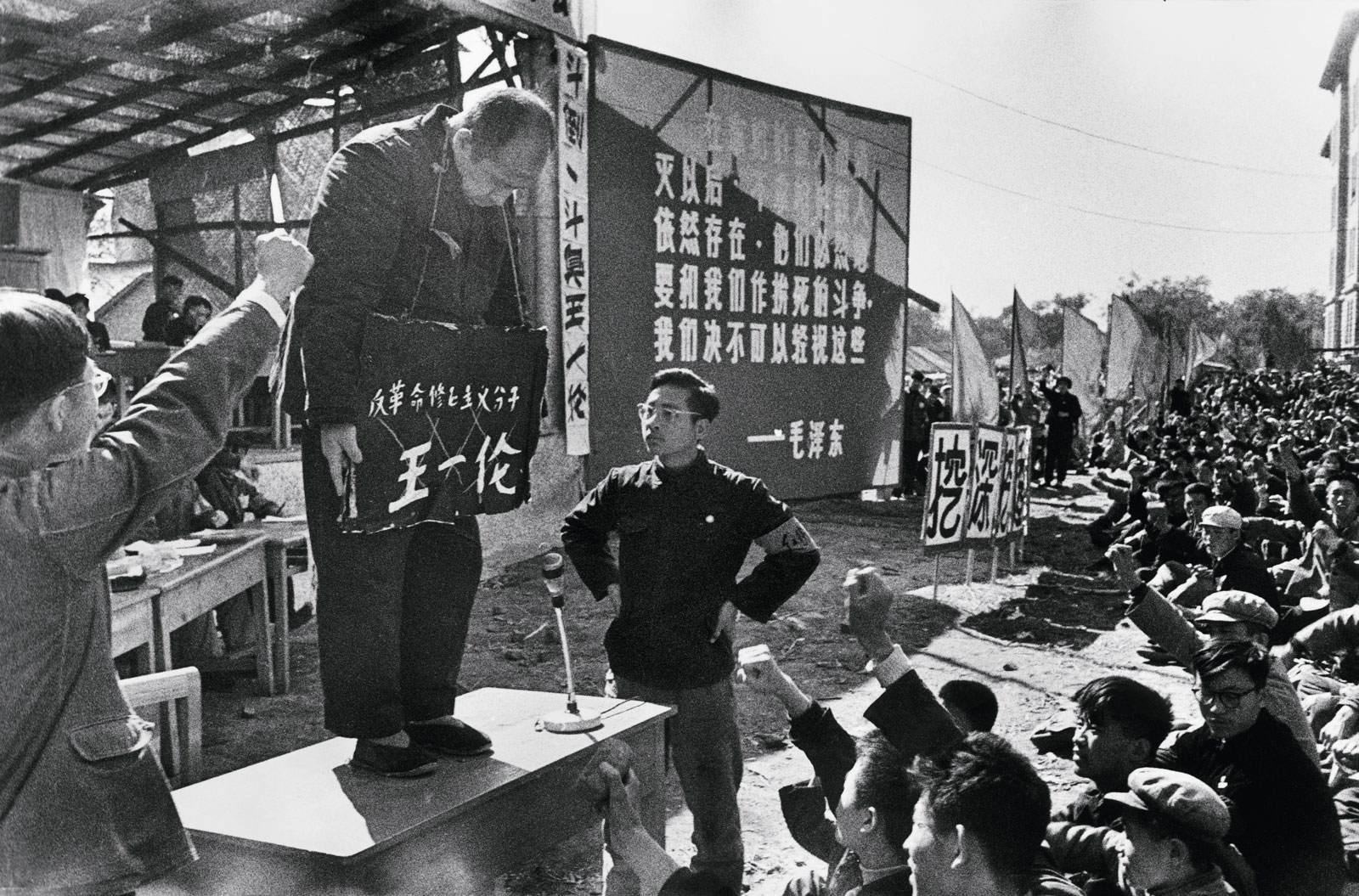

Provincial Party Secretary Wang Yilun, being criticized by Red Guards from the University of Industry and forced to bear a placard with the accusation “counterrevolutionary revisionist element,” Harbin, China, August 23, 1966. Li Zhensheng/Contact Press Images

By now, it has been nearly forty years since the Cultural Revolution officially ended, yet in China, considering the magnitude and significance of the event, it has remained a poorly examined, under-documented subject. Official archives are off-limits. Serious books on the period, whether comprehensive histories, in-depth analyses, or detailed personal memoirs, are remarkably few. Ji Xianlin’s The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, which has just been released in English for the first time, is something of an anomaly.

At the center of the book is the cowshed, the popular term for makeshift detention centers that had sprung up in many Chinese cities at the time. This one was set up at the heart of the Peking University campus, where the author was locked up for nine months with throngs of other fallen professors and school officials, doing manual labor and reciting tracts of Mao’s writing. The inferno atmosphere of the place, the chilling variety of physical and psychological violence the guards daily inflicted on the convicts with sadistic pleasure, the starvation and human degeneration—all are vividly described. Indeed, of all the memoirs of the Cultural Revolution, I cannot think of another one that offers such a devastatingly direct and detailed testimony on the physical and mental abuse an entire imprisoned intellectual community suffered. After reading the book, a Chinese intellectual friend summed it up to me: “This is our Auschwitz.”

To mentally relive such darkness and to record it all in such an unswervingly candid manner could not have been easy for an elderly man: Ji was over eighty at the time of writing. In the opening chapter, he confessed to having waited for many years, in vain, for others to come forward with a testimony. Disturbed by the collective silence of the older generation and the growing ignorance of the young people about the Cultural Revolution, he finally decided to take up the pen himself.

Originally published by an official press in Beijing in 1998, during a politically relaxed moment, The Cowshed probably benefited from the author’s eminent status in China. A celebrated Indologist, Ji was also a popular essayist and an avowed patriot who enjoyed good relations with the government. With genial, grandfatherly manners, he had become, in his august age, one of those avuncular figures revered by the public and loved by the media. The book has sold well and stayed in print. But authorities also quietly took steps to restrict public discussion of the memoir, as its subject continues to be treated as sensitive. The present English edition, skillfully translated by Chenxin Jiang, is a welcome, valuable addition to the small body of work in this genre. It makes an important contribution to our understanding of that period.

Reading Ji’s account again, however, has also renewed some of my old questions and frustrations. How much can we really make sense of a bizarre, unwieldy phenomenon like the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution? Can we truly overcome barriers of limited information, fading historical memory, and persistent ideological biases to have a genuinely meaningful and illuminating conversation about it today? I wonder. The delicate circumstances surrounding Ji’s memoir in China, in a way, demonstrate both the entangled complexity of the events and the precarious state of historical testimony.

Like other ordinary Chinese, Ji had no idea what the Cultural Revolution was all about when Mao Zedong launched it in 1966. Son of an impoverished rural family in Shandong, Ji had managed, through diligence and scholarship, to get a solid, cosmopolitan education in republican China. Having spent a decade in Germany studying Sanskrit and other languages, Ji returned with a Ph.D. to teach at China’s preeminent Peking University, where he soon became the chairman of its Eastern Languages Department. Though disliking the corrupt Chiang Kai-shek regime, he stayed away from politics, a field he’d never had any interest in. But when the Communists came into power in 1949, like most educated Chinese at the time, Ji saw hope for a stronger nation and more just society.

Being a political drifter, however, was no longer an option. Under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), mass mobilization and political campaigns became a national way of life and no one was allowed to be a bystander, least of all the intellectuals, a favorite target in Mao’s periodic thought-reform campaigns. Feeling guilty about his previous passivity, Ji eagerly reformed himself. He joined the Party in the 1950s and actively participated in the ceaseless campaigns, which had a common trait: conformity and intolerance of dissent. In the 1957 Anti-Rightist Movement, more than half a million intellectuals were denounced and persecuted, even though most of their criticisms were very mild and nearly all were Party loyalists. The fact that Ji was able to stay out of harm’s way was probably due to two factors: his poor peasant background and his reputation as one who never stuck his neck out and toed the Party line sincerely.

In fact, he was doing just that in the first year of the Cultural Revolution. Peking University was quickly transformed into a chaotic zoo of factional battles, with frantic mobs rushing about attacking professors and school officials labeled as capitalist-roaders-in-power. A bewildered Ji tried his best to keep a low profile by hiding in the crowds. But he had a vulnerable spot: he abhorred a cadre named Nie Yuanzi, the leader of the dominant Red Guard faction on campus. Although every faction in China claimed loyalty to Chairman Mao, Nie enjoyed a special status: she penned the very first big-character poster of the Cultural Revolution, attacking certain Peking University officials and received Mao’s personal endorsement for it. Disgusted by her bullying style, Ji decided, in an uncharacteristically rash moment, to join her opponents’ faction. This was a fatal mistake. Nie’s followers took their vengeance immediately: they raided Ji’s home one night, smashing furniture and digging up, inevitably, some ridiculous evidence that Ji was a hidden counterrevolutionary.

From that moment onward, Ji’s life became a dizzying descent into hell. The ensuing chapters in the book are the most shocking and painful to read. There are many searing, unforgettable vignettes. Ji’s meticulous preparations for suicide, which was aborted only at the last moment by a knock on the door. The long, screaming rallies where Ji, already in his late fifties, and other victims were savagely beaten, spat on, and tortured. The betrayal by his former students and colleagues. An excruciating episode in the labor camp: Ji’s body collapsed under the strain of continuous struggle sessions; his testicles became so swollen he couldn’t stand up or close his legs. But the guard forced him to continue his labor, so he crawled around all day moving bricks. When he was finally allowed to visit a nearby military clinic, he had to crawl on a road for two hours to reach it, only to be refused treatment the moment the doctor learned he was a black guard. He crawled back to the labor camp.

A noteworthy feature of The Cowshed is its entangled theme of guilt and shame. In memoirs about Maoist persecutions, authors typically portray themselves as either hapless, innocent victims or, occasionally, defiant resisters. The picture is murkier in Ji’s recollection. He writes about Chinese intellectuals’ eager cooperation in ideological campaigns and how, under pressure, they frequently turned on one another. He mocks his own “aptitude in crowd behavior” and admits that, until his own downfall, he had also persecuted others:

Since we had been directed to oppose the rightists, we did. After more than a decade of continuous political struggle, the intellectuals knew the drill. We all took turns persecuting each other. This went on until the Socialist Education Movement, which, in my view, was a precursor to the Cultural Revolution.

And what was his involvement in the Socialist Education Movement? “Without quite knowing what I was doing, I joined the ranks of the persecutors.”

To Ji, this is a forgivable sin because if he and many other Chinese intellectuals have been guilty of persecuting one another, it was largely because the intellectuals as a class had been compelled to feel deeply guilty and shameful about themselves. Ji described how this was achieved through the fierce criticism and self-criticism sessions, a unique feature of the Maoist thought-reform campaigns. Ji’s own ideological conversion was accomplished through such a ritual.

Impressed by the Communist victory and early achievements, he blamed himself fervently for not being sufficiently patriotic and selfless: he was selfish to pursue his own academic studies in Germany while the Communists were fighting the Japanese invaders; he was wrong to avoid politics and to view all politics as a tainted game, because the Communist politics was genuinely idealistic and noble. Only after beating himself up about all his sins did he manage to pass the collective review and gain acceptance as a member of the “people.”

Ji describes the overwhelming sense of guilt as “almost Christian,” which led to a feeling of shame and induced a powerful urge to conform and to worship the new God—the Communist Party and its Great Leader. Afterward, like a sinner given a chance to prove his worthiness, he eagerly abandoned all his previous skepticism—the trademark of a critical faculty—and became a true believer. He embraced the new cult of personality, joining others to shout at the top of his voice “Long Live Chairman Mao!” Through this process, millions of Chinese intellectuals cast off their individuality. For Ji, the feeling of guilt became so deeply engrained that, even after he was locked up in the cowshed, he racked his brain for his own faults rather than questioning the Party or the system.

Ji was obviously not a shrewd political animal or a deep thinker. Admitting that his eyes were finally opened only after the Cultural Revolution ended, he refrained from analyzing the larger political picture or interpreting the motives of those who launched the chaos. But he clearly felt that the country on the whole had failed to learn a real lesson from what happened. Toward the end of the memoir, he writes:

My final question is: What made the Cultural Revolution possible?

This is a complicated question that I am ill-equipped to answer; the only people in a position to tackle it refuse to do so and do not seem to want anyone else to try.

Ji was of course alluding to the Chinese government’s quiet ban on any deep probing of the subject, a policy still in effect today. First and foremost is the question of Mao. Everyone knows that Mao is the chief culprit of the Cultural Revolution. Well-known historical data points to a tangle of factors behind Mao’s motivation for launching it: subtle tension among the top leadership of the CCP since the Great Leap Forward, which led to a famine with an estimated thirty to forty million deaths; his desire to reassert supremacy and crush any perceived challenge to his personal power by reaching down directly to the masses; his radical, increasingly lunatic vision of permanent revolution; his deep anti-intellectualism and paranoid jealousy. But, from the viewpoint of the Party, allowing a full investigation and exposure of Mao’s manipulations would threaten the Party’s legitimacy. If the great helmsman gets debunked, the whole ship may go down. Mao as a symbol is therefore crucial: it is tied to the survival of the Party state.

Then there is the thorny issue of the people’s participation in the Cultural Revolution. The Red Guards were only the best-known of the radical organizations. At the height of madness, millions of ordinary Chinese took part in various forms of lawless actions and rampant violence. The estimated death toll of those who committed suicide, were tortured to death, were publicly executed, or were killed in armed factional battles runs from hundreds of thousands to millions. This makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to bring all of the perpetrators to account.

Consequently, the situation has been handled in a manner that reflects both cynical and pragmatic calculations: After arresting and blaming it all on the ultra-leftist Gang of Four, the government officially condemned the period as a “ten-year disaster,” tolerated a short period of limited public ventilation, then moved to contain the damage. It’s one of those noiseless bans done through internal control; investigation, discussion, and publication have been variously forbidden, discouraged, or marginalized. Over time, the topic has faded away as though it all happened quite naturally.

This situation is especially unsatisfying and unfair to those who suffered untold atrocities. Most of the teachers who were beaten up by their Red Guard students never received an apology. Most of the scholars who were tortured in the countless cowsheds continued, as Ji did, to live and work among their former persecutors. Some of the former perpetrators thrived in the new era, building successful careers and lives.

Ji himself worried about “stepping on people’s toes.” After writing the first draft of his memoir in 1988, he kept it in a drawer for years, for fear it might be viewed as a personal vendetta. He then revised it heavily, toning down his prose and keeping most of the persecutors unnamed. He said he wanted no revenge, just to write a honest historical document, so that young Chinese would know the past and would not let it happen again. He sounded apologetic about letting his emotions get the better of him in the earlier draft. Still, the reader can probably catch a strange tone of sarcasm and self-mockery in the narrator’s voice.

I found Ji’s tone odd and puzzling at first until it occurred to me that this is not an uncommon rhetorical device in Chinese writing or talking: to control seething anger or to deflect unbearable pain, one often turns to black humor or sarcastic hyperbole. A Chinese elementary school teacher who was tortured and jeered at in public struggle sessions during the Cultural Revolution told me that the sense of physical and psychological violation was so ferocious it felt like being gang-raped. He had nightmares about it for years. Later, a friend pointed out that he would adopt a facetious tone whenever he spoke about the experience. “I hadn’t noticed the tone myself,” he told me. “I think I turned it all into a joke because I can’t bear the pain and the shame with a straight face.”

Ji also seemed to suffer a survivor’s shame. Many scholars and writers committed suicide in the early part of the Cultural Revolution to avoid the indignities they faced, and he repeatedly mentioned his ambivalence about his failed attempt at suicide. This has to do with an ancient code of honor for a Confucian scholar. In the memoir, Ji recalls his first encounter after the Cultural Revolution with the senior apparatchik Zhou Yang. Zhou had supervised the persecution of many intellectuals until he himself was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. Zhou’s first words to Ji were: “It used to be said that ‘the scholar can be killed, but he cannot be humiliated.’ But the Cultural Revolution proved that not only can the scholar be killed, he can also be humiliated.” Zhou roared with laughter, but Ji knew it was a bitter laugh.

Ji Xianlin died in 2009. Two years after his death, a Peking University alumna named Zhang Manling who had been close to Ji published a piece about their friendship and made a few unusual revelations. In 1989, after the students began their hunger strike on Tiananmen Square, Ji and several other Peking University professors decided to publicly show their solidarity with the youngsters by paying them a visit. Ji, the oldest and most famous of the professors, traveled in high style: sitting on a stool on top of a flat-backed tricycle, which was fastened with a tall white banner that said “Rank One Professor Ji Xianlin,” the seventy-eight-year-old Ji was peddled by a student from the west-side campus across the city. When they finally arrived in Tiananmen Square, the students burst into delighted cheers.

During the post-massacre purge, at all the faculty meetings where everyone was forced to biao tai (declare their position), Ji would only say: “Don’t ask me, or I’ll say it was a patriotic democratic movement.” Then one day, Ji walked off from his campus residence, hailed a taxi, and asked to be taken to the local public security bureau. “I’m professor Ji Xianlin of Peking University,” Ji said to the police on arrival. “I visited Tiananmen Square twice. I stirred up the students, so please lock me up together with them. I’m over seventy, and I don’t want to live anymore.” The policemen were so startled they called Peking University officials, who rushed over and forcibly brought Ji back to campus.

It was, again, one of those high-pressured, terrifying and tragic moments in China’s long history. But this time, acting alone, Ji lived up to the honor of a true Confucian scholar.

Adapted from Zha Jianying’s introduction to Ji Xianlin’s The Cowshed: Memories of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, translated by Chenxin Jiang, which has just been published by New York Review Books.