Source: The World of Chinese (3/22/22)

How the War in Ukraine Inspired China’s Independent Filmmakers

By Siyi Chu (褚司怡)

A handful of independent short films promote empathy and compassion toward war victims in Ukraine.

“Ido remember my dad,” says Mark, a 32-year-old Russian-born Ukrainian man studying in Beijing. Dressed in a yellow Adidas hoodie and sitting hunched over on his bed, he shifts his eyes away from the camera as he continues softly, “Yeah, he loved me a lot.”

Shaky archival footage flits across the screen, of 1990s Ukraine shot from moving vehicles, as Mark recalls how his Russian father used to put him on his lap while driving. “I was imagining I was driving the car,” Mark says over shots showing young people goofing off by the roadside and a blurry rainbow-colored sunset.

Jia Yanan, a freelance filmmaker and photographer, shot Mark’s reminiscences in his Beijing apartment on March 6. That was the night before the city of Nikolaev, Mark’s hometown 250 miles south of Kyiv, was bombed. Jia made the as yet unreleased short documentary A Monologue About Home, telling Mark’s story, as part of an initiative called “Against the War, In the Name of Cinema,” which she first came across in the New Asian Filmmakers Collective WeChat group on March 2. The initiative called for impromptu, low-budget, non-commercial anti-war films to be submitted within one week to “raise our voices as Asian filmmakers,” while citing United Nations figures showing the war in Ukraine had seen 536 civilian casualties between February 24 and March 1.

The call-to-action, complete with black-and-white photos of Ukrainian civilians crowding bunkers, has attracted 12 filmmakers from Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and the PRC. Eight films have been released so far via the collective’s social media channels, CathayPlay, an online streaming site promoting Chinese independent films, and DOCO, a partnering WeChat account focused on documentaries. A further four are planned, on topics ranging from the role of art in the war, to interviews with Chinese who lost relatives in the war in Korea. While viewer numbers have been low so far, filmmakers hope to reflect on conflict, create empathy, and bring a human lens to the war in Ukraine, a topic which has often seen polarized and politically-charged debate in China.

The initiative is the work of Guo Xiaodong, an independent film producer and editor from Beijing, who co-founded the collective in 2016 as an alliance for Asian filmmakers to exchange ideas, resources, and collaboration opportunities. “Since the war started, the attitude from domestic and social media has been so ambiguous that it baffles me,” Guo tells TWOC over the phone on the evening of March 16, when the UN’s civilian casualty count had soared to 1,900. Sickened by what he perceived as indifference to the war in some areas of the media, Guo launched the initiative in part because: “It was too scary to me, that people of our time are thinking like this.”

For Jia, making her film about Mark was a way of understanding the human impact of war: “When you truly get to know someone going through the influence of war, you realize that their pain is almost impossible to describe,” she tells TWOC in a Beijing café, her childlike voice ordinarily punctuated by laughter suddenly solemn at this thought. “Audiences in China rarely get to know about such pain.”

A Monologue About Home turns out to be an intimate documentary that weaves together Mark’s ache for his family back in war-torn Ukraine and warm childhood memories. Footage is interspersed with on-the-ground clips from Ukraine including from Nikolaev as it was being bombed, but also birds flying and the sun setting outside of Mark’s window in Beijing. Jia hopes to create empathy through a personal tender narrative, writing in her director’s statement, “He is not a crying, nameless face we see on TV.”

Other directors taking part in the initiative take different approaches to empathy, and not all are as explicit in their references to the war in Ukraine. In his nearly 3-minute fiction film One Thought (released March 14), Zhao Xu’s reflections on war precipitated into a scene of a fish flapping around in a kitchen sink, the flip-flopping sound of the creature cross-fading into the invasive noise of machine guns from the radio. “Resistance against violence requires human compassion. If we want to embrace peace, we have to first not bring pain to other creatures,” Zhao, a 29-year-old independent film director from Inner Mongolia who is also a Buddhist, tells TWOC via WeChat.

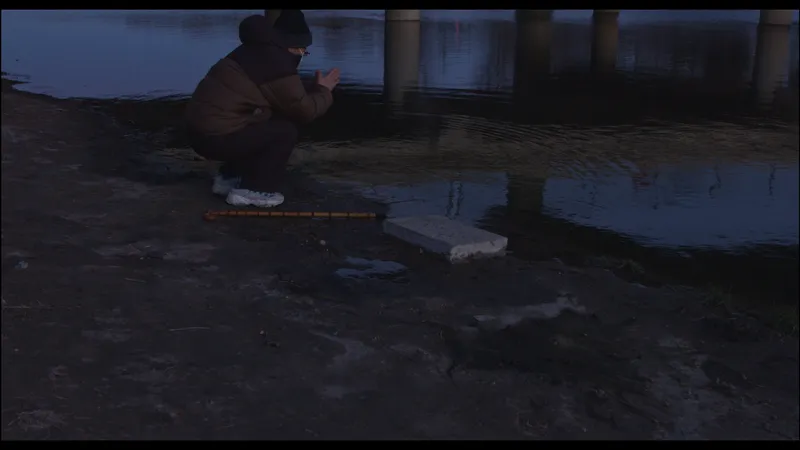

In the end Zhao has a human character, played by his grandfather, release the fish into a pond. Ever since Zhao started studying Buddhism, questions about life and death are often on his mind. “Animals faced with the threat of humans are also suffering as if from war…I hope my work passes along some kindness and hope, instead of fueling conflicts.”

At the end of Zhao Xu’s “One Thought,” the man prays by the pond after releasing the fish (screenshot from “One Thought”)

Meanwhile, Hua Zhenyi, based in Shanghai, captures ordinary life in China, forming a surreal parallel with the ongoing war. Changsha-based Sun Hongyan’s film pieces together interviews with a Chinese mother who lost her son to the war in Korea and visuals from Ukraine. These as yet untitled works will be released in the coming weeks.

Jia’s project almost didn’t work out. To find a subject to share their story, she contacted more than a dozen Ukrainians in Beijing, yet all but one turned her down due to the issue’s sensitivity. Even Mark texted Jia the second day of their interview, asking to discontinue the project, “but then his hometown was bombed, so he changed his mind,” Jia shares. She has been continuously sending versions of her edits for Mark’s input, believing this the fairest way to work with him.

Even before the rejections, Jia found it challenging coming up with a suitable film idea in such a short period of time. Originally, the film was going to be a montage of Servant of the People, a comedy starring Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, and footage from the current war, combined with footage of dance performance. But the dancer was unable to create the expression of suffering Jia envisioned, telling her that “Neither of us has experienced war. We can only create at a distance, as an onlooker,” Jia quotes. That critique made Jia decide to tell the story of individuals’ lived experiences from their perspective.

Shot and edited within a limited time period, the films vary in quality and content. “[Mark and his friends] often went swimming in the winter; he even gave me a clip of them swimming in the Dnieper,” Jia says. She wants to fit the scene into the film, but due to time limits is finding it hard: “I want to have more beauty in the film. Our heads are already filled with the image of Ukraine in victimhood.” But Guo believes the time-pressured results are still powerful, and that the tight schedule is necessary to stay “timely.”

The poster of Sun Hongyan’s short film showing her interviewee who lost a son to the war in Korea (Sun Hongyan)

A collage of photos from Hua Zhenyi’s filmmaking process, showing everyday realities in China and Ukraine side by side (Hua Zhenyi)

However, the public reach of the films remains low. At the time of writing, the most popular film on the collective’s WeChat video channel has accumulated 81 likes and 149 shares. The most viewed film on the collective’s Youtube channel has reached only 33 views—Vietnamese director Truong Mihn Quy’s 2 minute short silent film We Sit in Silence at the Memorial Table, shot while working on the set of another film in Russia that was discontinued because of the war.

“People in Chinese media like what we are doing, but they dare not publicize it,” Guo claims. “No one wants to tag onto ‘anti-war,’ because if anything goes wrong, who will be responsible?” he says, referencing the sensitivity of the war.

Some online posts expressing anti-war sentiment do appear to have been removed by Chinese social media platforms. On February 26, an open letter by five renowned historians from Tsinghua, Peking, Fudan, Nanjing, and Hong Kong Universities opposing the war and calling for peace was removed by internet censors 2 hours and 40 minutes after it was posted, according to The Guardian. On February 27, poet Yu Xiuhua posted a poem entitled I Wish that Poetry Can Withstand a Tank, denouncing the cruelty of war. The poem received more than 100,000 views, but it was met with criticism in the comments: “A person needs to have nationalistic sentiments…I finally see how shallow and pretentious you are,” read one; “You don’t understand politics, so it’s meaningless to write this poem,” went another. Now, the poem on her account is replaced by a warning from WeChat: “Unable to view this content because it violates regulations.”

But Zhao sees the arts as having “a subtler and more enduring role” when compared to such media posts. “It would be hard for art to directly change reality, but…I hope people who watch [my] film can imagine with empathy the pain and fear of those being killed, and thus cherish the lives around us now.”

Towards the end of A Monologue About Home, Mark recounts how his family used to cook together in Ukraine, and then sits down with the food he has just made in his Beijing apartment. Jia gets out from behind the camera, pulls up a chair, and joins him for a bite. “I wanted to point out the dynamic between us as a filmmaker and a subject…I don’t want to be an observer who does not participate,” Jia explains. “I wanted to say that even though I’m the one with the camera, I am with you.”

Full disclosure: The writer is involved in the initiative as a volunteer translator.