Source: Taipei Times (5/24/20)

Taiwan in Time: A great loss for Taiwanese literature

Chung Chao-cheng, who died last Saturday, didn’t learn Chinese until he was 20 — but he became one of Taiwan’s most celebrated Mandarin-language authors

By Han Cheung / Staff reporter

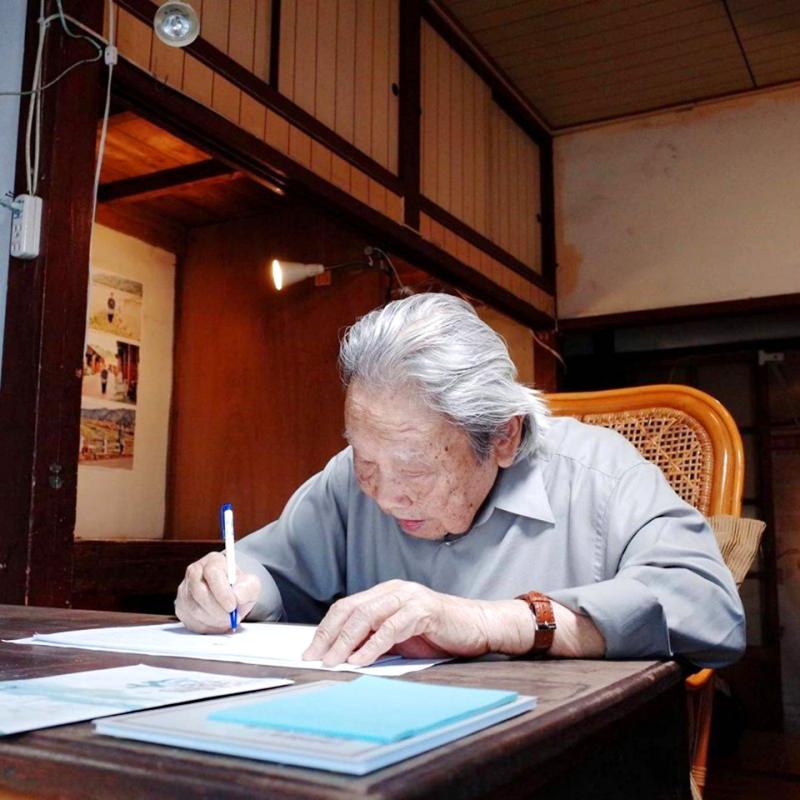

A portrait of Chung Chao-cheng in his later years. Photo: Taipei Times file photo

Three months before his 90th birthday in 2015, Chung Chao-cheng (鍾肇政) woke up shortly after midnight and experienced a inexplicable sense of clarity.

“Suddenly, my mind started going all over the place. There were some recent memories, but also many that I thought I had long forgotten. They would appear and disappear from my brain one after another, and they were so clear, so lucid. Even the memories from 70, 80 years ago felt like they happened yesterday. I suddenly thought, if I still remember so much, why don’t I write everything down?”

Despite his solid reputation among Taiwan’s literary giants, Chung had never felt comfortable writing a memoir, declaring his aversion in the introduction to the 1998 book, Memoirs of Chung Chao-cheng: Struggle and Uncertainty (鍾肇政回憶錄:徬徨與掙扎), a collection of personal essays put together by his friend Chien Hung-chun (錢鴻鈞).

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” he told himself. “Write down what you remember. Whatever you don’t remember, let it turn into foam with the waves, fly away with the wind, disappear into the passage of time. Hey, you 90-year-old geezer, try to capture everything that’s left in your deteriorating brain.”

“I got off my bed, wiped my face, fixed myself a glass of milk and lit a cigarette. I’ve decided to leave something behind — I don’t dare call it a ‘work,’ but, why does that even matter?”

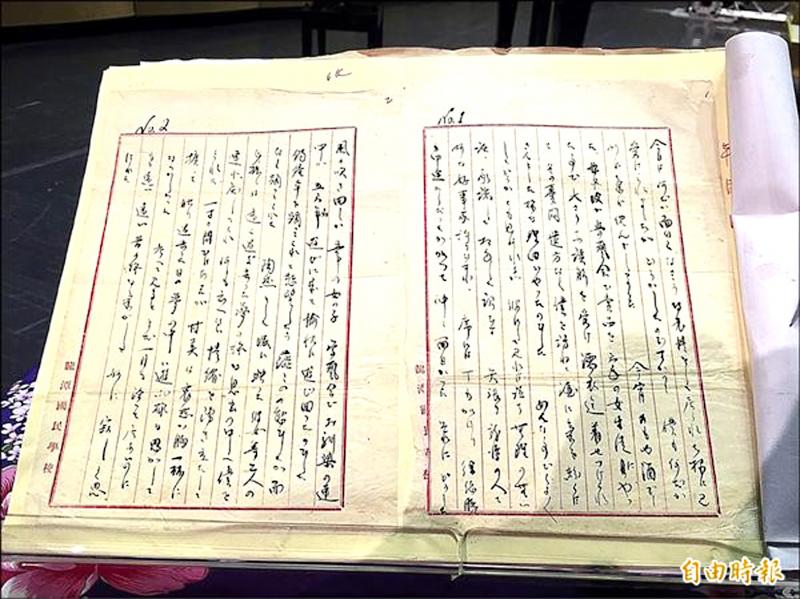

At the age of 90, Chung Chao-cheng donated to the Taoyuan City Government love letters he wrote as a young man. Photo: Lee Jung-ping, Taipei Times

Unfortunately, Chung never started his endeavor due to health issues, although he did publish a collection of love letters he wrote in his youth the following year. His son, Chung Yen-wei (鍾延威), finished the memoir for him and published it as Climbing a Mountain (攀一座山) last December, in time before Chung died last Saturday.

TRANSLINGUAL BLUES

Born in 1925, Chung was a prominent member of the “translingual generation” (跨語言的一代), referring to writers who were educated in Japanese but were forced to switch to Mandarin when the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived in 1945.

A portrait of Chung Chao-cheng. Photo: Hsieh Wen-hua, Taipei Times

Although Chung would become a tireless champion of Hakka culture starting in the 1980s, his beloved “mother tongue” was actually his third language, having grown up in a Hoklo- (also known as Taiwanese) speaking village and learning Japanese at school.

When he moved back to his father’s Hakka hometown of Longtan (龍潭) at the age of seven, the local kids relentlessly teased him for not speaking the local tongue, calling him a “Hoklo shit” (福佬屎).

Chung was 20 years old when the Japanese left. Excited to be free of foreign rule, Chung discarded his Japanese books and began studying Chinese classics in the Hakka.

Chung Chao-cheng’s former residence in Taoyuan City’s Longtan District is now Chung Chao-cheng Literary Park. Photo courtesy of Taoyuan City Department of Hakka Affairs

A school teacher by profession, Chung held classes in Hakka. The government, however, soon ordered that only Mandarin be used. Chung had to start from scratch, spending a year mastering zhuyin fuhao (注音符號, Mandarin phonetic symbols commonly known as Bopomofo).

“There’s no shortcut to switching languages,” Chung said. “I had to master Mandarin so I could express my thoughts.” He tried to use it as much as he could, peppering the Japanese letters he wrote to his friends with Mandarin phrases, although he had to translate them in his mind first.

LITERARY RESISTANCE

Chung Chao-cheng inscribed “Longing for the Spring Breeze,” the title of one of his novels, on this stele in his hometown of Longtan. Photo courtesy of WIkimedia Commons

Although he published his first story “After Marriage” (婚後) in 1951, Chung’s subsequent submissions were mostly rejected. Opportunities were scant for Taiwanese authors during the early days of KMT rule not just because of the language barrier, but also due to the party’s censorship of all published materials and championing of anti-communist and war literature.

Chung saw this as blatant discrimination, and was especially incensed when fellow Hakka writer Chung Li-ho’s (鍾理和) masterpiece Lishan Farm (笠山農場) was rejected over and over again. At the height of White Terror in 1957, Chung started a newsletter to unite Taiwanese writers, a dangerous act that could have landed him in prison.

“One had to be tactful back then,” he said. “I even declared that I wanted to establish Taiwanese literature as a branch of Chinese literature. I had to mask my true intentions otherwise I would become a victim of the White Terror … I wanted to find kindred spirits, but to me it was also a form of resistance.”

Officials kept a close eye on him, especially after he hosted a gathering of Taiwanese writers in Taipei. The police raided their second meeting, but the host managed to convince them that there was nothing subversive going on. Chung says while he discontinued the newsletter after the incident, the friendships remained and they encouraged each other to keep writing and submitting.

Eventually, they received recognition for their work. Chung published his first full-length novel, The Dull Ice Flower (魯冰花), in 1962 with the help of Lin Hai-yin (林海音), then-editor of the United Daily News literary supplement (聯合報副刊). Lin recognized the value of these writers and helped edit their clunky Mandarin.

“Dull Ice Flower was actually very critical of society … including Chung’s disappointment toward the ‘motherland’ and its treatment of Taiwanese,” Chung Yen-wei writes in Climbing a Mountain. “He skillfully masked these sentiments through the touching storyline, and the book became a huge hit. He became famous overnight.”

It only took 15 years after Chung Chao-cheng first picked up a Chinese book to become a recognized writer in the language.

After the lifting of Martial Law in 1987, Chung was finally able to embrace the Hakka culture and language that both governments he lived under had tried to stamp out. In August 1988, he participated in the inaugural Hakka Culture Summer Camp, and on Dec. 28, he took to the streets and joined the “Return My Native Language” (還我母語) march.

“When the Hakka language disappears, the Hakka people will too,” he lamented in 2015.

STRUGGLE AND UNCERTAINTY

Although his son chose the title Climbing a Mountain for the memoir, Chung chose Struggle and Uncertainty as a title for the 1998 personal essay collection.

“For much of my life, I’ve been repeatedly experiencing these two words. As someone in his 70s, my heart should be still, clear and harmonious — but I still feel endless struggle and uncertainty,” he writes in the introduction.

After publishing Furious Waves (怒濤) in 1993, Chung’s output declined as he became preoccupied with his activism and other cultural activities. Having been writing nonstop in addition to teaching for over 40 years, Chung felt great unease toward his lack of productivity.

“I need to take a break — but when I’m resting, I still struggle and feel uncertain,” he says. “Because I haven’t been writing much, I also feel immensely anxious. Not writing is like a death sentence to a writer’s life. How can I let life just pass by blankly? All I have left in my life is struggle and uncertainty.”

Chung would soon pick up the pen again.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.