Source: SCMP (1/8/20)

Starring Hu Ge and with a plot worthy of Raymond Chandler, film noir by Diao Yinan is a Chinese box office hit, and he says it’s a genre he’ll stick to

Why change a winning hand? Director of The Wild Goose Lake, who’s spun China-set films noir into gold, says he’ll pursue the genre and make films even better. Diao’s films are notable for their style, and he cites influences from Francois Truffaut and Robert Bresson to Chen Kaige and Jia Zhangke.

by James Mottram

Director Diao Yinan (left) and actor Hu Ge in a still from The Wild Goose Lake.

According to Chinese filmmaker Diao Yinan, there are two types of director.

One will continue pursuing a particular thematic and stylistic trajectory from film to film, “whereas some other directors will take a very different path”, he says. “After one success, they might want to try something thematically or stylistically completely different. Like Kubrick, say.”

As anyone who has seen Diao’s work will know, he’s very much in the former camp, “thinking about continuities”, as he puts it, “and how I’m going to stay on that particular thematic and stylistic track”.

A genre filmmaker who has become increasingly obsessed with the rich framework afforded by film noir, the 50-year-old Diao has already triumphed in this arena, with 2014’s Black Coal, Thin Ice.

Diao’s bleak tale of a murder, in which Liao Fan’s detective tries to piece together the mystery of a dismembered corpse, won the Berlin Film Festival’s top prize, the Golden Bear, with the best actor award also going to Liao.

So it’s no surprise the writer-director has decided to continue on that same neon-soaked path in his latest film, The Wild Goose Lake.

Originally written before Black Coal, Thin Ice, Diao put it aside because he was not satisfied by the direction the script had taken. Then a news report about a so-called “Congress of Thieves” in Wuhan, central China, around 2012 helped him shape the story. Criminal representatives from important sites in each Chinese province gathered to exchange experiences and divvy up territories – until they were caught.

Diao used this “congress” as a central idea in The Wild Goose Lake, in which gangsters come together in a seedy hotel basement to learn about the art of mass motorbike theft.

“We do have these motorbike-stealing gangs that are very prominent in certain parts of China, especially suburban areas and small villages,” says Diao, who decided to “combine” this with the idea of a multi-province criminal network.

Gwei Lun-mei in a still from The Wild Goose Lake.

In Diao’s hands, this coming together of gangsters is the starting point for a fiendish, flashback-riddled, rain-lashed film noir so complex it would probably give American crime writer Raymond Chandler a headache were he alive today.

The film’s lead character, Zhou Zenong (played by Shanghai-born star Hu Ge) is forced to go on the run after he accidentally kills a police officer in the aftermath of the aforementioned meeting, which goes awry.

Naturally, there’s a femme fatale – in the shape of Liu Aiai (Black Coal, Thin Ice’s Gwei Lun-mei), a prostitute who gets embroiled with Zhou and sees the bounty on his head as a means to escape her dismal existence. But the labyrinthine plotting is secondary in The Wild Goose Lake to the remarkably assured style of Diao’s directing.

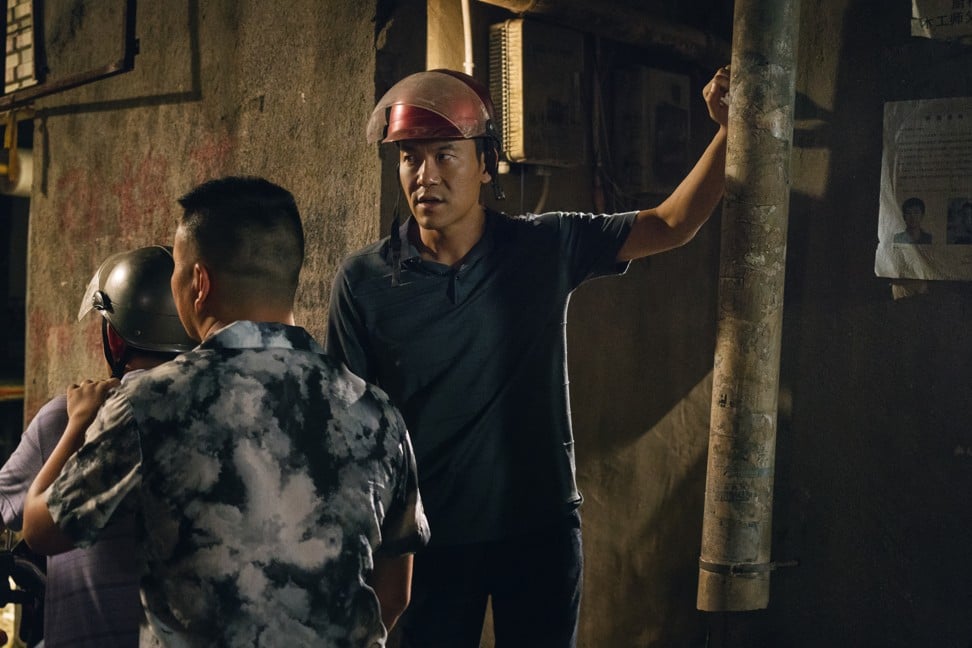

Hu Ge in a still from The Wild Goose Lake.

Diao reunited with cinematographer Dong Jinsong on The Wild Goose Lake, and its portrayal of the seedy underbelly in an unnamed city in southern China is highly evocative.

Shot largely at night, filming took five months to complete, as the limited hours of darkness in the summer meant they only had an average of seven hours a night in which to film. The highly choreographed action sequences, including visceral motorbike chases, added to the challenges.

Then there’s Diao’s penchant for shooting lengthy takes.

“I’m someone who enjoys doing long takes,” he says. “I feel a sense of accomplishment when I successfully finish them. It’s very rewarding for me as a director. Sometimes, if I don’t shoot any long takes, I actually feel uncomfortable. It’s something that gives me comfort: to conceptualise a long take and execute it just the way I wanted, and that really brings a lot of accomplishment for me.”

As for the stylistic influences on The Wild Goose Lake, he points to his formative years in college. Born in Xian, in the northwestern province of Shaanxi, Diao attended the Central Academy of Drama, where he devoured the films of the French New Wave – and those of François Truffaut, in particular – alongside those of Robert Bresson and Michelangelo Antonioni.

“These are all the major filmmakers that inspire me to make films in such a stylistic way,” the director says.

There were other influences too.

His mother was a theatre actress, and Diao used to spend days watching her work during rehearsals. His father, meanwhile, was an editor of the Xian Film Studio magazine West Film and, during his high school years, Diao was able to see close up the work of several of the studio’s employees.

One film in particular, Chen Kaige’s 1984 film Yellow Earth, was particularly memorable; Chen is one of the so-called Fifth Generation of Chinese filmmakers (the first to graduate following the end of the Cultural Revolution in China, which lasted from 1966 until 1976).

Hu Ge (left) and Gwei Lun-mei in a still from The Wild Goose Lake.

Diao remembers his father bringing him an early draft of the script, and the fact that the finished version of Yellow Earth was considerably different to that early draft made a strong impression on him. So, too, did Chen’s aesthetic sensibilities.

“Someone who actually has something to say in such a stylised way and has a very, very interesting perspective – not only in terms of form, but in terms of its visual film language, the way the filmmakers see the world – is something I admire and look up to.”

Initially, Diao worked as a screenwriter for other directors, including Zhang Yang (for 1997 anthology Spicy Love Soup and the Beijing-set follow-up Shower). He made the leap to directing after meeting a group of other budding directors, including Jia Zhangke (whose own recent Ash Is Purest White feels like a kindred spirit to The Wild Goose Lake). They’d eat, drink, swap ideas and influence each other, he says.

Diao’s 2003 debut Uniform centred on a young man who impersonates a police officer, and was set against the backdrop of economic unrest in Shaanxi province. Social commentary, though, is always “a by-product” of the story he wants to tell, Diao says.

“I’d love to see audiences appreciate that aspect as well. But it’s something that comes naturally and organically, rather than intentionally and purposefully trying to make a statement.”

His sophomore film Night Train involved a female prison guard unwittingly dating a man whose wife was executed on her watch, but – influenced as he was by the hard-boiled crime stories of the 1940s – Diao was trying to move towards film noir. As he recently told US film magazine Film Comment, his earlier scripts “were written with that same feel to them, but it was very difficult to find the market for them”.

Liao Fan in a still from The Wild Goose Lake.

That’s changed now. The Wild Goose Lake is a hit in mainland China, where it has grossed 190 million yuan (US$27.3 million) in its first 10 days of release. As for his next project, Diao says he has no plans to change a winning formula.

“I just want to make sure I’m making even better films on the same trajectory,” he says. “That is the only pressure I feel – how can I make it even better?”