Source: SCMP (12/20/19)

Based on a heartbreaking true story: China’s abandoned children remembered in short film

Chinese filmmaker Yuchao Feng believes his short film Pearl can help heal the wounds of the past for his family and many others who have suffered a similar fate. Feng based his short film Pearl on his mother’s account of being abandoned by her own mother in Fujian province at the age of six

By Kylie Knott

A scene from Chinese filmmaker Yuchao Feng’s heartbreaking short film Pearl, which is about child abandonment and is based on his mother’s childhood.

One Sunday afternoon in February, 2017, Chinese film director Yuchao Feng was in his flat in the US state of New Jersey when he received a phone call from his mother that would shock and inspire him.

Feng knew something was wrong – not just because it was 3am in the northern Chinese city of Tianjin, where Wang Jingjing was calling from, but because they rarely spoke.

“My parents were not around much when I was growing up in Ningde,” says Feng, recalling the city of three million in Fujian province, in the country’s southeast, known for its tea cultivation. “And we talked even less after I moved to the US to study film in 2011.”

Feng’s mother was having a nightmare similar to those that had plagued her for more than 40 years. As they talked, he learned that she had been abandoned by her mother at the age of six, a secret she had kept bottled up for decades. For the first time in years, Feng felt close to his mother.

“I wanted to dig deeper into my mother’s psyche, to know her better,” he says.

Feng did just that. The experience inspired him to write and direct Pearl, a heartbreaking short film set in a fishing village in Xiapu county, Fujian where his mother grew up, in which a poor widow (played by Liu Lu) abandons her six-year-old daughter to seek a better life with her son. The young girl, Lin, portrayed beautifully by first-time actress Yating Cao, is destined for a much harder life, which would have been typical, Feng says.

A still from Feng’s short film Pearl.

“The girl would have to grow up very quickly while taking care of her elderly nana, who has dementia and is unable to take care of herself. The role is sadly reversed. A stark reality and a bleak future awaits the six-year-old,” Feng says.

“Back in the day that town, like many, was male-dominated. Thousands of women suffered widespread societal misogyny. In the story, the mother had to choose between her daughter and her son. Given the circumstances, and the time and place, the choice was sadly obvious.”

In 1995, a documentary called The Dying Rooms looked at the dire conditions endured by children, mostly girls, who had been abandoned by their parents to avoid having to pay the hefty fines imposed under China’s one-child policy, the family planning programme introduced in 1980 as part of measures to control the country’s rapidly growing population.

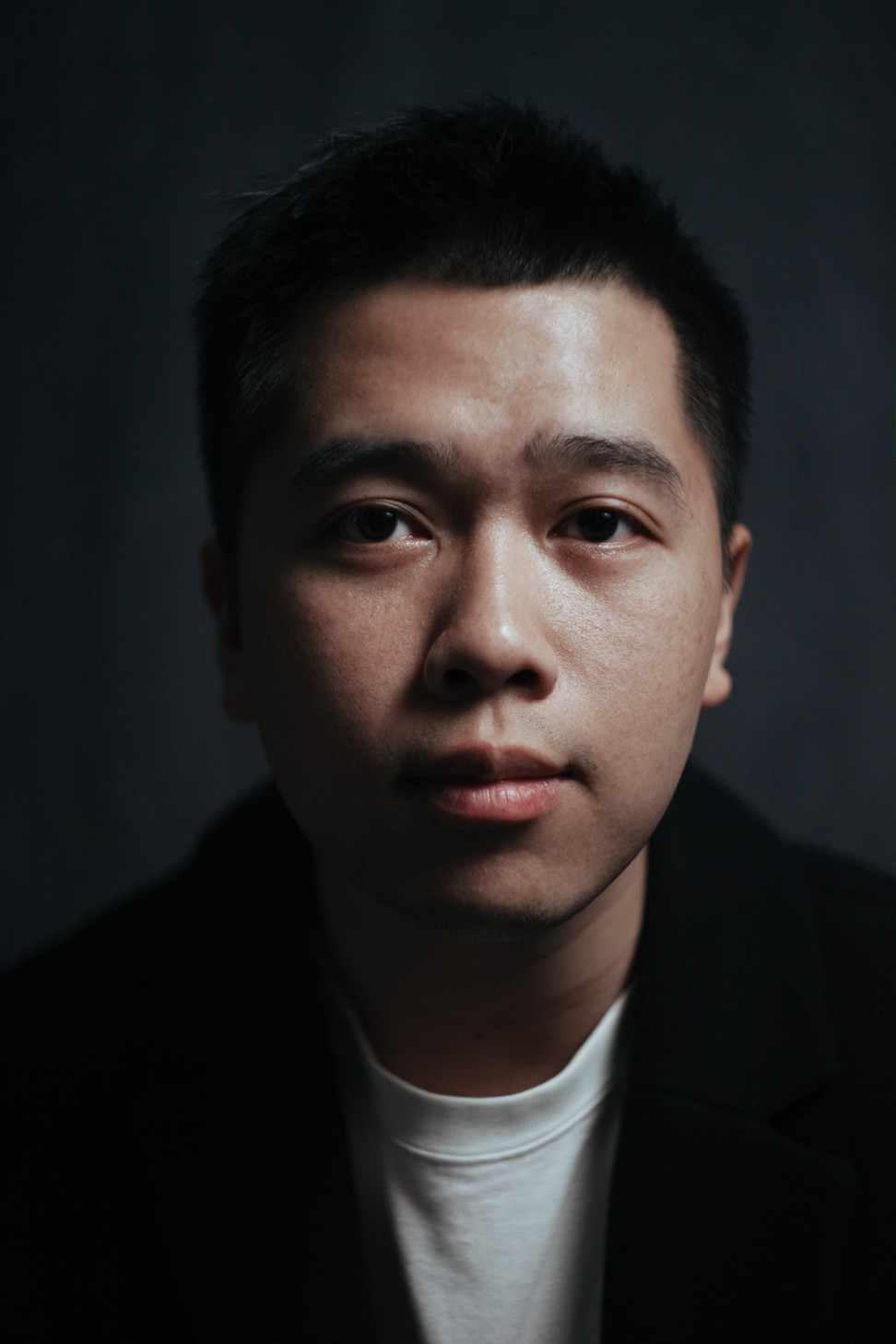

Yuchao Feng.

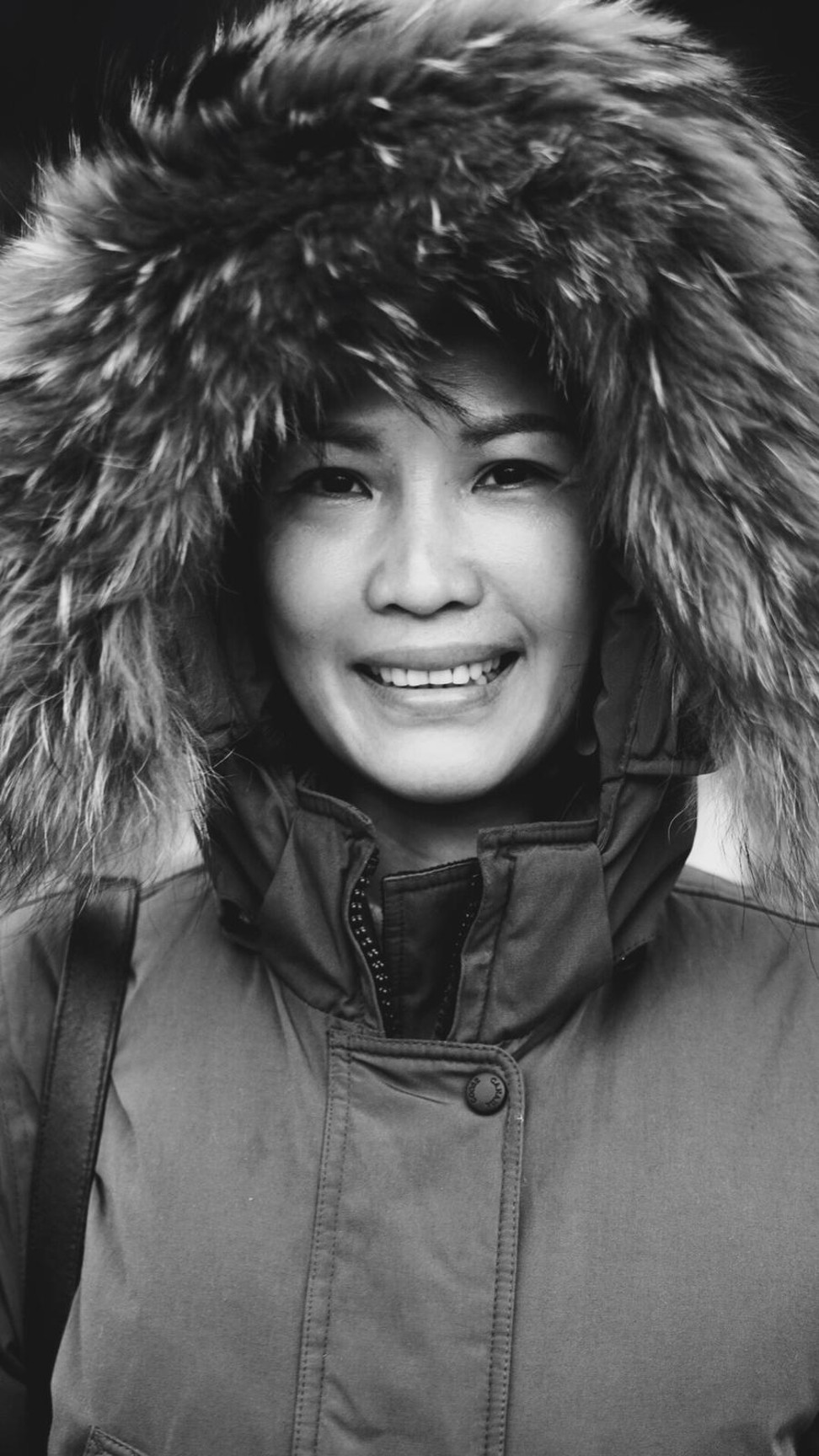

Wang Jingjing

Today, China is a different place. The one-child policy was relaxed in 2015 and the country has been riding a wave of economic growth. But with the boom has come a new generation of abandoned kids.

Called “left-behind children”, they are mostly the offspring of China’s 288 million rural migrant workers, the driving force behind the country’s spectacular growth. With limited access to education and health care, these children – a 2017 report by Unicef, the United Nations Children’s Fund, estimates there are 61 million of them – who usually live with grandparents or other relatives, can be separated from their parents for years; many suffer psychological problems ranging from antisocial behaviour to suicidal tendencies.

The abandonment of children is a global problem, and a big one. According to the UN, about 60 million children and infants around the world have been abandoned by their families and live on their own or in orphanages. Psychiatrists have sought to define a condition they call abandoned child syndrome, the symptoms of which would include social alienation, guilt, low self-esteem, insomnia and nightmares, eating disorders, anger issues, depression and substance abuse.

Feng says that while his mother has reconnected with the mother who abandoned her, she still cannot shed all the pain from being abandoned. “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to forgive her,” she told her son during that emotional phone call. He says the film has become a bridge that has brought him closer to his mother.

“We now talk on the phone much more than we used to. My mother has been scarred since childhood. Now, all she wants is to feel a bit of love. I must be there for her.”

He says it was vital that the film was shot on location in Xiapu county, a place that today attracts photographers lured by the landscape of vast mudflats staked with bamboo poles used for drying seaweed and cultivating oysters.

Xiapu county is known for its vast mudflats staked with bamboo poles used for drying seaweed and collecting oysters. Photo: Shutterstock

“I wanted to stay true to my mother’s experience, and shooting the film where the heart of the story happened helped add emotional truth to the storytelling,” Feng says.

“The water, the bamboo and the moss-covered bricks, it was about bringing that piece of memory back to life in the most authentic way possible. It was of course heart-wrenching to be in the centre of my mother’s tragic upbringing, but it was also strangely liberating to capture the unique aesthetics of this particular memory on film,” says Feng, who trained in cinematography.

The location was a draw card for many involved with the film, including producer Linhan Zhang, a graduate of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, whose mother also hails from Fujian province. “That was the immediate bond,” Zhang says. “I haven’t seen a lot of stories filmed in Fujian, so this was a great opportunity to represent this rustic but little-known village to the world.”

Feng believed it was vital that the film was shot on location in his mother’s home of Xiapu county.

Zhang also praises the film’s Danish director of photography, Lasse Ulvedal Tolboll.

“Lasse brought a coldness often seen in Scandinavian films to a Chinese environment and achieved a delicate balance that neither highlights nor glorifies the griminess of the village,” says Zhang.

Pearl has resonated with audiences since its official release in May, earning selections at film festivals in Vancouver, Melbourne and Tokyo, and receiving a Special Jury Mention at New York’s Tribeca Film Festival.

Another of its producers, Canadian-born Clifford Miu, is also a Tisch School of the Arts alumnus and, along with Zhang, founded Bering Pictures – a production company that targets young filmmakers wanting to tell stories with a positive social impact. Miu was also deeply moved by the script.

“Someone close to me was a victim of abandonment at a young age, so the story hit me hard … I could empathise with the young character’s suffering,” says Miu, who spent most of his formative years in Taipei and whose credentials include work on Martin Scorsese’s Silence, which was shot in Taiwan.

“Yuchao had a personal stake in the story, and knowing that this film helped strengthen the relationship between him and his mother was something I found unusual and deeply moving.”

A still from Feng’s short film Pearl.

Miu believes the issues of abandonment resonates on many levels.

“Abandonment is a universal subject,” he says. “Everyone has at some point felt abandoned or suffered the grim regret of being responsible for abandoning something – a place, an object, a relationship.

“I think it’s the global theme of abandonment – including child abandonment – and the moving performances of the on-screen talents that really touched the hearts of audiences.”

Miu says Feng’s “brilliant decision” to tell the story through the eyes of a child is another reason why it has struck a chord.

But casting those young eyes was an intense process. “I visited preschools [in Xiapu county] hoping to find the perfect young actress, but to no avail,” says Feng. He met more than 100 girls before discovering Yating in a dance class.

“Most girls were excited by the idea of becoming a ‘movie star’. Not Yating. She showed no visible interest and was more introverted than the other candidates. Her rebellious attitude and sensitive demeanour convinced me she was perfect for the role. But I had to spend a long time persuading her – and her mother – to let her act in our film.”

Casting her “brother” (another first-time actor, Menghua Zhong) proved less stressful.

“I visited a preschool around our shooting location and when I saw the boy, I immediately knew we had to cast him.”

Feng says working with children during the six-day shoot was a challenging but fruitful experience.

“I knew early on that working with two young children was going to be difficult, but even then there were moments during the shoot in which I felt truly battered. The tough weather conditions were taxing – not just for the children but for the entire crew.”