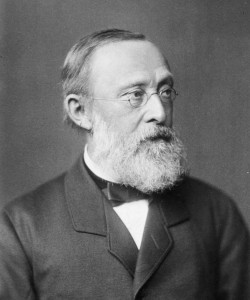

Evolving reflection on Virchow and why he was chosen and what we learned

At first glance, Virchow seemed like an ambitious scientist as in any other time. However, once we delved deeper we found that only every belief v\Virchow held was a product of his circumstances. for example, he originally wanted to be a priest in order to help the poor but his speaking voice was not very strong, and this altruistic spirit comes from his upbringing in a rural town with much poverty. The political and social movements during his schooling and while studying at the Wilhelm-Friedrich Institute greatly impacted his thoughts and ideas. During his studies there was unrest about poverty, and Virchow saw this firsthand in Berlin as urbanization was on the rise and more people trying to live in already cramped quarters increased the problems, yet the rulers did nothing to help the situation. These conditions motivated Virchow to enact change and when he was appointed to his first position at a university he put his job and credentials on the line to participate in the revolution of 1848. This surprised us during our initial research, because not many other scientists would have sacrificed so much for a cause not connected to them and keep their reputation intact to go on to make great contributions to the field (because most would have been imprisoned or killed, probably). Later, Virchow continues to fight for the end of poor living conditions and poverty by beginning his political career in Berlin in the Reichstag. Here, he clashes with Otto Von Bismarck time and time again. This interaction allowed us to also learn more about another very important person in not just Berlin history but also that of Prussia and later a united Germany. Their Sausage Duel was perhaps the most interesting development in their political rivalry and showed Virchow’s cunning and intellect to win an argument even when potential death is on the line where he is “outgunned”.

Medical History Museum at Charite

Virchow holds so much prestige as a scientist, that his extreme involvement in political movements and organizations was an interesting addition. The draw to learn about Berlin through Rudolf Virchow was his significant impact on the field of microbiology, one of our group member’s area of study. He not only made great advances by creating the field of cellular pathology, and with it journals that continue to allow the spread of information about this important study. His legacy lives on in the Charité Hospital, where he taught for many years and developed a substantial amount of pathological specimens to educate his students with. Witnessing Virchow’s contributions to medicine and science in a very physical manner was a privilege. After the tour, it’s very clear that Virchow has had a profound and lasting effect on the medical advances in Berlin.

When visiting the medical history museum in one building of the Charité, it was fascinating to see that Virchow was not the only researcher present to be honored. In particular, Paul Ehrlich was a prominent figure. A whole floor was dedicated to his work in immunology, hematology, and staining methods. Learning about a German physician who worked in a time period overlapping with Virchow, who also had an impact on Germany’s medical advances and won a subsequent Nobel prize award, has been an enlightening experience. Currently, the Paul Ehrlich Institut in Langen works on vaccines.

Berlin and Columbus Similarities, Differences, and Interconnections

One of the first similarities noticed was the prevalence of bikes. Columbus is becoming a more bike-friendly city, with construction of designated lanes and more education about bicycle etiquette and safety. In both cities, the cyclists ignore road laws, put pedestrians in danger, and are generally aggressive. However, in Berlin the cyclists tend to use bells or horns more often than screaming at those who might get in their way. This highlights a major difference in culture, with Berliners and Ohioans noise-levels. As we have established in class discussions, Berliners and Germans in general do not speak or ask someone to move if someone is in that person’s way, rather they just wait impatiently or push through the person and do not apologize. Ohioans, on the other hand, will apologize many times, say “excuse me”, or call out in case of a bike. This is a very noticeable cultural difference, one which is telling of the more private and reserved Germans and the louder and (to us, more polite, because of the cultural bias that we grew up with) Ohioans.

There are far more differences. One of the most obvious ones lies in the public transportation system. In Columbus, we just have COTA, and CABS on Ohio State Campus. In smaller towns, there are less options with more “regional” buses. Here in Berlin, the methods of transport are extremely varied: buses, trams, subways, trains, long-distance trains, and even boats! In addition, they are very punctual and organized. If there are changes in schedules, passengers are informed. COTA lines don’t give any indication as to when the next bus is arriving at any point, let alone if there were any issues. However, it has become obvious that when certain problematic events occur, such as the S-Bahn strike in Berlin, or snow emergencies in Columbus, parts of public transport access become free.

View from the hill behind our hotel.

A similarity is the green space in both Columbus and Berlin. Both cities are very focused on incorporating green trees and plants into the city, and they keep the parks very clean. Certain parks that we visited in Berlin were more clean than others depending on the area we were in (Prenzlauer Berg compared to Kreuzberg, for example) while in Columbus parks throughout the city are about the same in terms of level of cleanliness. One difference is the size of the parks. Obviously, Columbus does not have a park to rival the Tiergarten of Berlin but Berlin also has smaller parks scattered throughout the city. In Columbus, since the city is relatively new compared to Berlin, this difference is probably due to city planning, and everything in Columbus was planned based on practicality whereas Berlin has changed over hundreds of years, and has gone through many more city planners than Columbus, thus creating more various parks.

Another large difference is the language barrier. In Columbus, nearly everyone speaks English. Here in Berlin, not only is German a prominent language, but Turkish, Russian, Greek, Italian, English, and many others. When one walks the streets, they may not understand anything that someone else is saying. If there is a situation that requires communication, sometimes there is a struggle to find a common language to interact in. In Columbus, you would not hear so many different languages because it does not have as many inhabitants that come from “migrant” backgrounds.

is regarded as the foundation of modern pathology and is still referenced today. Rudolf was the first person in history to name and document various diseases such as leukemia, embolism, and thrombosis. He also was the first user of such terms as chromatin, agenesis, and spina bifida. Rudolf developed the first comprehensive guidelines for autopsy using surgery and microscopic examination of all body level cells. One of his most important discoveries, one which affected Berlin directly, was his discovery of the transmission cycle of roundworm common in Europe which established the practice of meat inspection. When Rudolf died in 1902 he was called the “Pope of medicine” by his colleagues due to his founding of social medicine and advancement of public health.

is regarded as the foundation of modern pathology and is still referenced today. Rudolf was the first person in history to name and document various diseases such as leukemia, embolism, and thrombosis. He also was the first user of such terms as chromatin, agenesis, and spina bifida. Rudolf developed the first comprehensive guidelines for autopsy using surgery and microscopic examination of all body level cells. One of his most important discoveries, one which affected Berlin directly, was his discovery of the transmission cycle of roundworm common in Europe which established the practice of meat inspection. When Rudolf died in 1902 he was called the “Pope of medicine” by his colleagues due to his founding of social medicine and advancement of public health.