I’ve made the decision to wrap the guest lectures of Geoffrey Parker and Jean-Vincent Blanchard into one blog entry, because I became fascinated with a sentiment they each expressed independently but which was worded so similarly by both of them as to be almost an uncanny echoing. Parker and Blanchard claimed that after studying their subject for an extended period of time they had penetrated his psychology far enough that they could anticipate actions, responses, etc. They had, in effect, opened up little hatches and climbed inside the minds of Philip II and Cardinal Richelieu. And that was the moment they realized it was time to begin writing about this person.

Their claims sounded like nothing so much as the words of a competent actor preparing for a role. Parker categorized this kinship that the biographer must feel with his subject as a species of friendship, but I would propose a more neutral term: compassion. In his book To the Actor, Michael Chekhov writes:

Compassion may be called the fundamental of all good art because it alone can tell you what other beings feel and experience. Only compassion severs the bonds of your personal limitations and gives you deep access into the inner life of the character you study, without which you cannot properly prepare.

Worth noting is how much this concept of compassion and psychological oneness with the subject are relatively new developments in the history of biography. As the purpose of biography has shifted away from its earlier roots as a tool to model an ‘ideal life’ for its readers, it has increasingly entered into a realm of exploration of individual psyches in a way that is reminiscent of the shift towards psychological realism in theater.

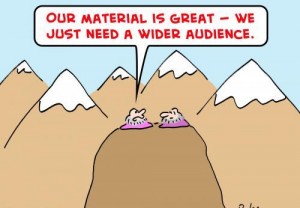

Another engrossing point which was raised through these guest lectures was the problematic topic of audience. In its current manifestation, biography, it would seem, more so than strictly scholarly writing or essays, is meant to be consumed by a broader audience. There is a warmly human aspect to the genre in that it traces the life of an individual person including his or her habits, haunts, milieu, upbringing, education, friendships, great loves, minor loves, marriages, lack thereof, great deeds, self-serving deeds, intellectual life, accomplishments… In effect, drawing the reader into another place, time, and mind than their own through the myriad familiar details of a human life.

But who is the audience? In the most effective directing class I ever took as an undergraduate, our professor insisted that this particular question must always be somewhere at the forefront of a director’s mind. Arguably, the same is true for any artistic pursuit. Writers write with the intention of publishing. Actors rehearse with the intention of performing. Considering one’s audience is an absolute necessity in this case because they will eventually be consumers of your work. If you alienate them entirely, your work will go un- or under- consumed. Vachtangov, a famous Russian director, was once asked, “Why do all the plays you direct, and especially the innumerable details you elaborate for your actors, always get across to the audience with unmistakable success?” Vachtangov’s answer was, approximately, “Because I never direct without imagining an audience attending all my rehearsals. I anticipate their reactions and follow their ‘suggestions’; and I try to imagine a kind of ‘ideal’ audience in order to avoid the temptations of tastelessness.”

Both Parker and Blanchard touched on this ultimate need to consider one’s audience. Parker discussed trimming his original material considerably in the interests of overall appeal to a wider audience; Blanchard came straight out and claimed that his original intent was to write a more readable and enjoyable biography of Richelieu than those that existed. Contemporary theater is rife with such conflicts. Professional companies worry about dwindling audience numbers, financial viability and what kind of performances would attract younger/newer/different audience members to the theater on an almost constant basis. Part of that struggle is being savvy about your product and always remaining aware of who your intended audience is.

Finally, I was intrigued by Blanchard’s revelation that Richelieu was a bit of a theater fanatic. He would no doubt be pleased to know that his own life had been dramatized in a 1839 historical play Richelieu; Or the Conspiracy. Coincidentally, this play is the source of the famous adage “The pen is mightier than the sword.” In 1870, Edward Sherman Gould, a literary critic, wrote that the play’s author, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, “had the good fortune to do what few men can hope to do: he wrote a line that is likely to live for ages.”

In the end, the goals of a playwright and a biographer aren’t as disparate as they might seem.