Disclaimer: I do not own any images displayed or material presented. This is purely for educational purposes

Nelson, G. for (2015). Researchers examine why sharks mistake surfers for their intended prey. Daily Mail Australia. Retrieved from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3031958/Researchers-examine-sharks-mistake-surfers-intended-prey.html.

Norén, L. (2009). Seeing Sharks. Retrieved from https://thesocietypages.org/graphicsociology/2009/page/3/.

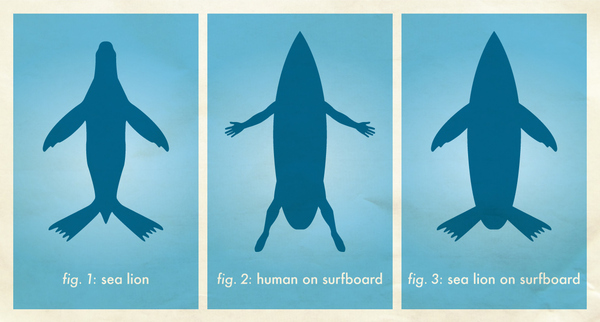

While shark attacks rarely kill humans, in contrast, we annually kill about 20-30 million sharks in the fishing industry or for sport, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Department of Ichthyology. Sharks are animals, they act on instinct, they do not just attack or hold grudges as seen in many shark movies. When humans are jumping and swimming around the water, it signals the shark of potential prey, much like a fish in distress. Contrary to popular belief, sharks don’t actually mistake us – people – for the seals that they normally eat. The way a shark hunts is mainly to test if it is worth their energy to try and kill an individual prey, they do a hit-and-run tactic to ‘test’ the prey to determine if it is food. Shark’s eyes are keen, but some images that they normally do not see, like a human, may confuse them. They simply might not know what it is they are looking at. Even though they can see a human, “sometimes that’s not enough for a shark, they want to feel what it is. When this happens, the shark will place its jaws over the object, scientists call this ‘mouthing’. The shark clamps down with the same bite force as a human, hardly anything to a shark. The reason for this is to get an idea of what the object is, and if it’s worth pursuing further interest” (Drift). Such an incident is called an attack for record-keeping purposes but compared to what sharks can and routinely do to seals makes an incident like this actually pretty tame in contrast.

Godknecht, A. (2004) Sharks Are Masters of Seven Senses. Shark Foundation – Foundation for Research and the Preservation of Sharks, Shark Foundation / Hai-Stiftung. Retrieved from https://www.shark.ch/Information/Senses/index.html.

Seeing under water is only possible from 0 to ~50 meters, depending on the water conditions. In addition, colors are absorbed more strongly with increasing water depth. Under these circumstances the advantage lies with whomever has better eyesight, be it predator or prey. Sharks have developed methods of amplifying light in their eyes which make them more efficient than such night-hunting mammals as cats, foxes or wolves, and yet we perceive that sharks mistake surfers for seals.

RA Martin, Neil Hammerschlag, and Ralph Collier from the ReefQuest Center for Shark Research argue that a “shark’s vision is too good and its sense of smell too sophisticated to confuse us [people] with a seal. These are supreme ocean predators and are highly unlikely to make clumsy and possibly costly mistakes.” (BBC News). The first blood draws a shark, but now we see that sharks are much more complex than we thought. Sharks have senses not available to most other animals.

Pressure-sensitive pores scattered over their head and down the body mean they detect the slightest changes in pressure, enabling them to discern the smallest of movements even when other senses are restricted—such as their sight in murky water. They also possess sophisticated electroreceptors which help them home in on the tiny electrical fields present around all living things, even creatures buried in sand. So, when we swim, they can detect that we are in the water and where the most activity can be felt. Such highly-tuned animals are not likely to misidentify something as large as a human being, hence why they ‘hit-and-run’ a human. It is implied by most scientists today that sharks such as Great Whites see humans as other predators that could compete with them for food.

Generally, when sharks attack people they are not interested in eating the people, they want the people to leave the area. Scientists “Martin, Hammerschlag and Collier have studied many shark attacks and say that prior to targeting a human, they show aggressive postures as a warning, and when that message is ignored they take action”, which is why sharks usually let go after the first bite, and the victims is left with a missing limb or a chunk of flesh missing (BBC News). It has been a little over 40 years since Jaws changed our perception of the ocean, and slowly but surely its grip is relaxing. There is an increase in concern for shark welfare and a greater understanding of the creatures as fascinating and impressive predators. The calls for their protection are getting louder and although most people find it hard to love them, sharks are garnering more respect. We are less likely to criminalize them and more prone to accept their presence.

TBC in Part 3: https://u.osu.edu/kociba.5/2019/09/25/fact-vs-fiction-reality-of-sharks-and-their-future-3-3/

References:

Choi, C. (2010). How ‘Jaws’ Forever Changed Our View of Great White Sharks. Live Science. Retrieved from www.livescience.com/8309-jaws-changed-view-great-white-sharks.html.

Godknecht, A. (2004) Sharks Are Masters of Seven Senses. Shark Foundation – Foundation for Research and the Preservation of Sharks, Shark Foundation / Hai-Stiftung. Retrieved from https://www.shark.ch/Information/Senses/index.html.

(2015). How Jaws Misrepresented the Great White. BBC News. Retrieved from www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33049099.

Martin, R. A. (2012).Biology of Sharks and Rays: Vision and a Carpet of Light. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved from www.elasmo-research.org

Meyer, C.G. (2004). Sharks can detect changes in the geomagnetic field. Journal of the Royal Society. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16849172

Mislinski, P. (2014). Why Do Sharks Attack? Discovery, Oceana. Retrieved from www.discovery.com/tv-shows/shark-week/about-this-show/why-do-sharks-attack/.

Nelson, G. for (2015). Researchers examine why sharks mistake surfers for their intended prey. Daily Mail Australia. Retrieved from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3031958/Researchers-examine-sharks-mistake-surfers-intended-prey.html.

Norén, L. (2009). Seeing Sharks. Retrieved from https://thesocietypages.org/graphicsociology/2009/page/3/.

Phillips, T. (2017) Why Do Sharks ‘Attack’ Humans? More than Just Mistaken Identity… Drift Surfing. Retrieved from www.driftsurfing.eu/why-do-sharks-attack-humans-more-than-just-mistaken-identity/.