In the summer of 1857, the United Kingdom was flooded with newspaper stories about a young lady, Madeleine Smith, arrested and tried for the murder of a poor clerk, Emilie L’Angelier. Smith was accused on three accounts; two attempts of poisoning with the intent to murder (as L’Angelier had been mysteriously sick twice before his death) and one charge of murder. After a trial that last more than a week, Smith was acquitted on one charge of Not Guilty and two charges of Not Proven, the latter being something rather unique to the Scottish judicial system.

And this despite the incredible amount of circumstantial evidence against her.

In my previous post, I described the analysis I had done in the Vane case and some future direction I planned to take following that. In this post, I relate my findings so far as well as the directions these findings have taken me.

Over the past weeks, I’ve found many similarities between the real Madeleine Smith case and the fictional Harriet Vane case. Both women had lovers outside of the bonds of marriage, with whom they were connected for about two years. Both women were accused, in the trials, of poisoning said lovers after quarreling with the men on multiple occasions before finally succeeding in killing them, and both were accused of using arsenic as their weapon. Why Smith is acquitted and Vane is not was something I found particularly interesting to explore over the past couple weeks, especially as Sayers includes two specific references to Smith in Strong Poison.

Having carefully read several newspaper accounts of Smith’s case and the more recent analysis of her trial in the book, Victorian Murderesses by Mary S. Hartman, I noticed, besides some minor details, three very specific ways that Sayers caused the Harriet Vane trial to deviate from Smith’s: class, appearance, and female agency.

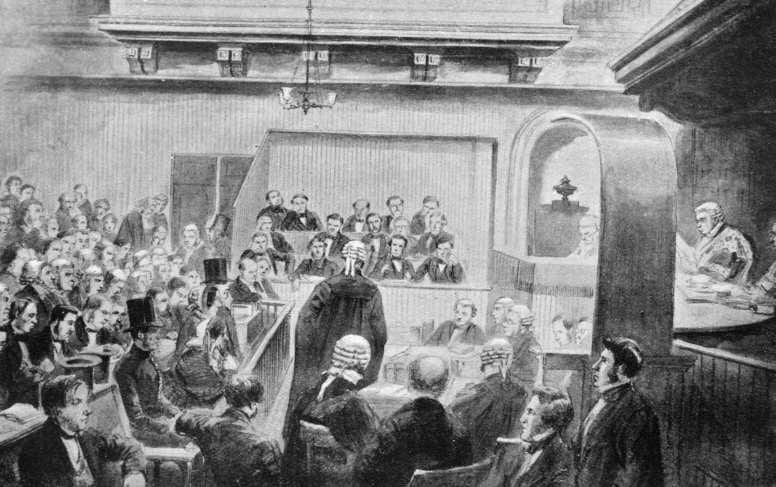

Throughout the Madeleine Smith trial, the press largely sympathized with Smith, praising her for her composure throughout the trial, and if they thought she might be guilty, likening her to a ‘fallen woman’ who had tried to release herself from the tyrannical hold of a seducer. I found only a few accounts that criticized Smith, and even these were more critical of her lover than the accused woman herself. Where the fictional Harriet Vane gained no sympathy from the spectators, other than, of course, Lord Peter Wimsey, Madeleine Smith had support not just from the press, but seemingly the whole United Kingdom, seeing as the audience at the trial cheered when she was acquitted. The case became a sensation, a household name, and an event to which later cases of poisoning were compared, real and fictional as we see in Sayers’s Strong Poison.

The first striking thing about the newspaper accounts of Smith’s trial was the amount of space dedicated to describing the woman’s appearance. Multiple articles describe in detail everything they can about her physical appearance from each article of clothing she wears, to the shape fo her face and the color of her eyes. Others stress her behavior, how “her features express great intelligence and energy of character,” and the composure that she maintains during the entirety of the trial without seeming to tire (Reynolds’s Paper). This I found especially interesting when compared to Harriet Vane, who was “not even that pretty,” (Sayers, 18), and when she is described, has a face that borders on being masculine, with “Her eyes, like dark smudges under the heavy square brows,” (Sayers, 1).

Then of course there is Smith’s societal class, which the papers make clear is fairly high, perhaps middle to upper-middle. Around the time that she is arrested, the press stresses that “The thought that a highly and virtuously bred young lady could destroy her lover is too appalling for belief…” (The Examiner). Vane is not even close to being in the same class. When she was not much older than Smith, her parents both died, forcing her to support herself on her detective novels (Sayers, 4).

Where Smith had beauty and class standing to protect her, Vane clearly has neither. She is poor, older, and not particularly beautiful, which are most likely deliberate choices made by Sayers in her creation of the accused criminal-turned-sleuth. Even more deliberate however, is the way Sayers portrays Vane as compared to the way the press portrays Smith.

As I said before, the press largely sympathizes with Smith throughout the summer of 1857. Though Smith’s guilt or innocence is up in the air, L’Angelier is clearly portrayed as her guilty, conniving seducer. No matter whether Smith poisoned him or not, and as Hartman points out it is very likely she did, the press clearly takes away any agency Smith has in this affair and the events following. If she didn’t poison him, then she is being unjustly dragged to court. If she did then either she was a desperate ‘fallen woman’ who was trying to get out of a bad situation, or she was turned into a cold, calculating murderer due to the influence of her evil lover. The newspapers took away any agency she had in the affair and consequent murder of L’Angelier, and as Hartman’s analysis implies, Smith was more than happy to take on the role provided for her (Hartman, 82).

Vane on the other hand, refuses to let any agency be taken from her. Sayers makes it clear in the summing up of her character’s trial that Vane chose to walk into the relationship with Boyes, and she chose to walk out of it (Sayers,4-5,6-7). The judge himself is clearly surprised by Vane’s annoyance and refusal of her lover’s marriage proposal and clearly implies that he thinks her foolish for this reaction (Sayers, 7).

This idea of the role of female agency, and the portrayal of female agency, especially caught my attention, especially because it seems a very deliberate thing for Sayers to put in. After all, agency plays a large part in the later Vane books, and is even part of the larger subjects of marriage as well as female education and employment, in her novel Gaudy Night.

Obviously, there are multiple topics to be explored. Firstly, how interested was Sayers in true crime and Madeleine Smith’s trial in particular? Despite clear differences, there are so many parallels between Smith and Vane that it’s more likely than not that she knew about Smith’s case. Secondly, the role of that verdict, “Not Proven,” was something fairly unique to the Scottish judiciary system, and it may be interesting to see what role the ability to make a verdict of ‘Not Proven’ played in Smith’s case (interestingly, it is rather similar to the outcome of the Vane trial, in which the jury are unable to agree on a verdict, thus giving Wimsey time to prove Vane’s innocence). I also plan to continue studying Adelaide Bartlett and Florence Maybrick, as well as a few fictional poisoners. Thanks to the book, Chemical Crimes by Cheryl Blake Price, I’ve discovered several fictional female poisoners that I think would be fascinating to study.

Other avenues of research could look at the role of age and education (specifically knowledge about medicine and poisons) play in poisoning trials, as education on medicine played a role in the Adelaide Bartlett case. I have also, for the most part, avoided the important role of race in the Smith Trial. I do not mean to downplay the importance of race in the portrayal of Smith and L’Angelier, but I will simply not be focusing on it in my research, as there is already plenty of great work done on the use of racial stereotypes in trials and periodical articles of those trials.

Bibliography

“Latest Intelligence. The Examiner, London, British Library Newspapers, Part I:1800-1900, Saturday, April 4, 1857, Issue 2566.

“Madeleine Smith Profile.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MadeleineSmithProfile.png

“Madeleine_Smith_Trial.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Madeline_Smith_Trial.jpg

Price, Cheryl Blake. Chemical Crimes: Science & Poison in Victorian Crime Fiction. The Ohio State University Press, 2019.

Sayers, Dorothy L. Strong Poison. Hodder & Stoughton, 2016.

“The Trial of Miss M. Smith at Edinburgh for Poisoning.” Reynolds’s Newspaper, London, British Library Newspapers, Part I:1800-1900, Sunday, July 5, 1857, Issue 360.