On its surface, professionalism seems like a competency that should be mastered prior to entry into medical school. After all, showing up on time, dressing appropriately, treating people respectfully, behaving with integrity and honesty, and holding oneself accountable for their responsibilities are basic expectations in any line of work. Medicine is no exception, however, its acuity and demanding nature can strain people in different ways – at times sparking lapses in professionalism from even the most resolved and well-intentioned individuals. Such slips (within reason) appear to be tacitly understood with the expectation that as the moment passes and tensions cool, lessons will be learned that can hopefully guide behaviors in similar situations moving forward. This is where the nebulous concept of professionalism reveals an underlying substantial, challenging, and essential skill to be honed: resiliency.

For some, medical school represents a second wave in an already full and enriching life. For me, a student who entered straight from college (which I entered straight from high school), medical school represents the first sustained challenge I have faced in my life. Prior to my arrival in Columbus, professional success had always come readily, easily, and frankly, expectedly. My personal resolve was certainly tested at times, but these challenges occurred within discrete time frames accompanied by the promise that the gravy train would again be chugging along in short order. While I understood that things were going to get tougher in medical school, I was frankly unprepared for the impending sense of inadequacy I would experience upon suddenly being placed among the most intelligent, driven, and accomplished group of peers I had ever been part of in my life (by an unspeakably wide margin).

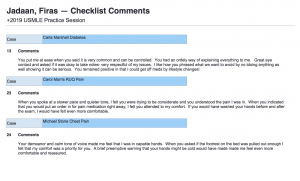

In the past I never had reservations about speaking my mind, but I unfortunately found myself questioning the value of my contributions early on in medical school. My belief that my peers were too smart, talented, wise, and experienced to take my observations seriously left me silent during group discussions, as expressed by my peers’ early LG evaluations (shown below).

These reservations not only brought previously unrecognized personal insecurities to light, but demonstrated an inadvertent lapse in professionalism on my part. Though I had exhibited the most superficial tenets of professionalism, my behavior utterly lacked features of collaboration, collegiality, and a commitment to excellence. Furthermore, I was denying my peers another source to feed into the communal discussion. Over the following two years of LG, I slowly but deliberately worked to address this issue, and as I did I found myself enjoying our group meetings more and carrying so much more from our discussions. I believe my peers acknowledged this development, as evidenced by my final LG evaluations (shown below).

When the core educational objectives were first presented to us, I frankly viewed “professionalism” as trite and uninspired filler. After all, how can one develop professionalism? Have we not already been deemed “professional” through our admission to professional school? Will I be assigned a babysitter to dress me in the morning and slap my wrist if I say something naughty?

Ultimately I found professionalism to be the most critical and difficult competency to develop, but also the most rewarding. While I only illustrated one example of my personal development, the last four years have marked the most dramatic evolution of my character over my entire life. The demands and pressures of medical school have exposed personal shortcomings that have otherwise flown under the surface while I previously glided fairly effortlessly through life. Being forced to face these limitations not only allowed me to address them specifically, but each instance strengthened my resiliency allowing me to more effectively identify and take on the next inevitable challenge. The story I shared here was one of the simplest obstacles I overcame in medical school, but was arguably the most difficult to traverse given how inexperienced I was at the time. I am certain that my greatest hurdles are yet to come, but I am now so much more comfortable with the notion of being challenged. Four years ago I was constantly terrified of scarring my ego, but now I yearn for further opportunities for growth – with their accompanied bruises, shortcomings, and all.