Philosophy:

We are a molecular cell biology lab. We use methods of molecular genetics, molecular biology, cell biology, bio-imaging, bioinformatics, and biochemistry. Methods are our means to an end. Our goal is to contribute to advancing the understanding of how life works. We are grateful to those scientists whose goal it is to invent and improve technology.

1. Structure and Function of the Plant Nuclear Envelope

We study the proteins that reside in the plant nuclear envelope, and specifically a protein complex called the LINC complex (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton). LINC complexes comprise a component anchored to the outer nuclear envelope and exposed to the cytoplasm, and a component anchored to the inner nuclear envelope and exposed to the nucleoplasm. Together, they span the nuclear envelope double membranes and create a direct physical link between these compartments. In animals and humans, they are involved in nuclear structure, mechanical signal transduction, genome organization, gene regulation, nuclear positioning and movement, and a variety of physiological and developmental processes. Our lab – together with Drs. Evans and Graumann at Oxford Brookes University, UK – has only recently discovered the plant equivalents of the animal LINC complexes. Together with collaborators, we have shown that they are involved in moving nuclei through pollen tubes (important for plant male fertility), the anchoring of Ran signaling, nuclear morphology, nuclear positioning in guard cells, and resistance against an oomycete pathogen. However, the mechanism by which these complexes operate is currently a wide-open question.

To discover these mechanims, we are investigating cytoplasmic and nuclear interactors of plant LINC complex components, their precise role in male fertility and guard cell function, additional novel nuclear envelope proteins, and LINC complex homologs in other plant species. In this context, we are interested in all aspects of nuclear movements in plants, and specifically in those that are related to plant-microbe interactions, both in pathogenesis and in symbiosis. Towards that end, we have started to work on an additional plant model organism, Medicago truncatula, that is host to both nitrogen-fixing bacteria (nodulation) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.

Key Reading:

Zhou X, Groves NR, Meier I. (2015). SUN anchors pollen WIP-WIT complexes at the vegetative nuclear envelope and is necessary for pollen tube targeting and fertility. J Exp Bot. 66: 7299-7307.

Zhou, X., Groves, N.R., and Meier, I. (2015) Plant nuclear shape is independently determined by the SUN-WIP-WIT2-myosin XI-i complex and CRWN1. Nucleus 6:144-153.

Zhou X & Meier I (2014) Efficient plant male fertility depends on vegetative nuclear movement mediated by two families of plant outer nuclear membrane proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(32):11900-11905.

Zhou X, Graumann K, Wirthmueller L, Jones JDG, & Meier I (2014) Identification of unique SUN-interacting nuclear envelope proteins with diverse functions in plants. The Journal of Cell Biology 205(5):677-692.

Griffis, A.H.N., Groves, N.R., Zhou, X., and Meier, I. (2014). Nuclei in motion: movement and positioning of plant nuclei in development, signaling, symbiosis and disease. Frontiers in Plant Science 5.

Zhou, X., and Meier, I. (2013). How plants LINC the SUN to KASH. Nucleus 4, 206-215.

Zhou X, Graumann K, Evans DE, & Meier I (2012) Novel plant SUN–KASH bridges are involved in RanGAP anchoring and nuclear shape determination. The Journal of Cell Biology 196(2):203-211.

2. Anchoring of Ran Signal Transduction in Plants

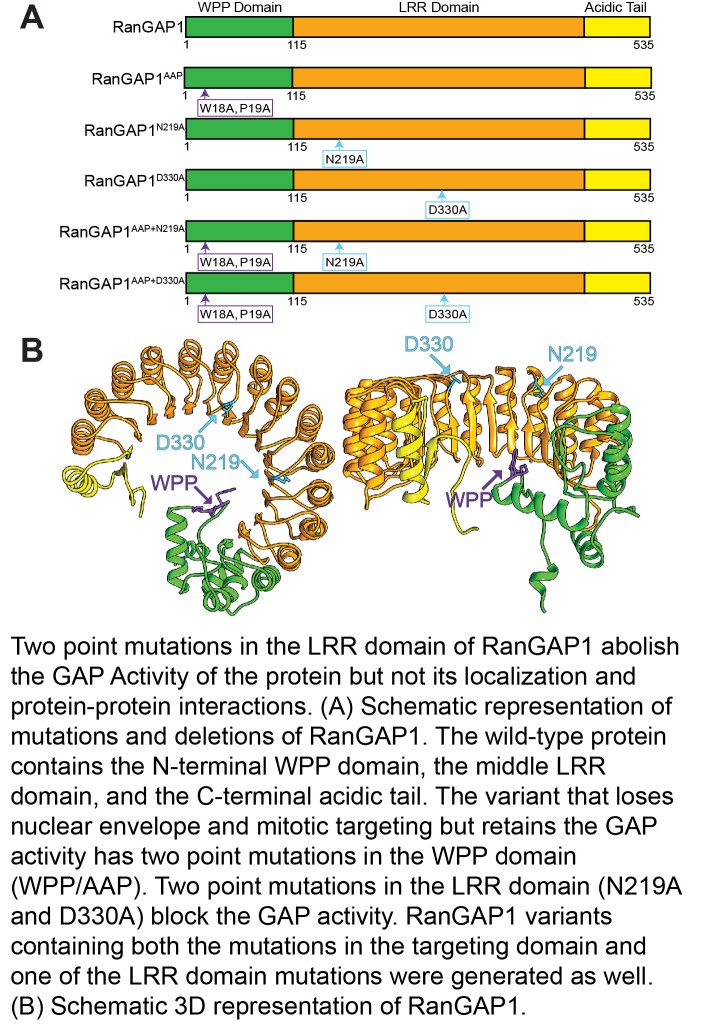

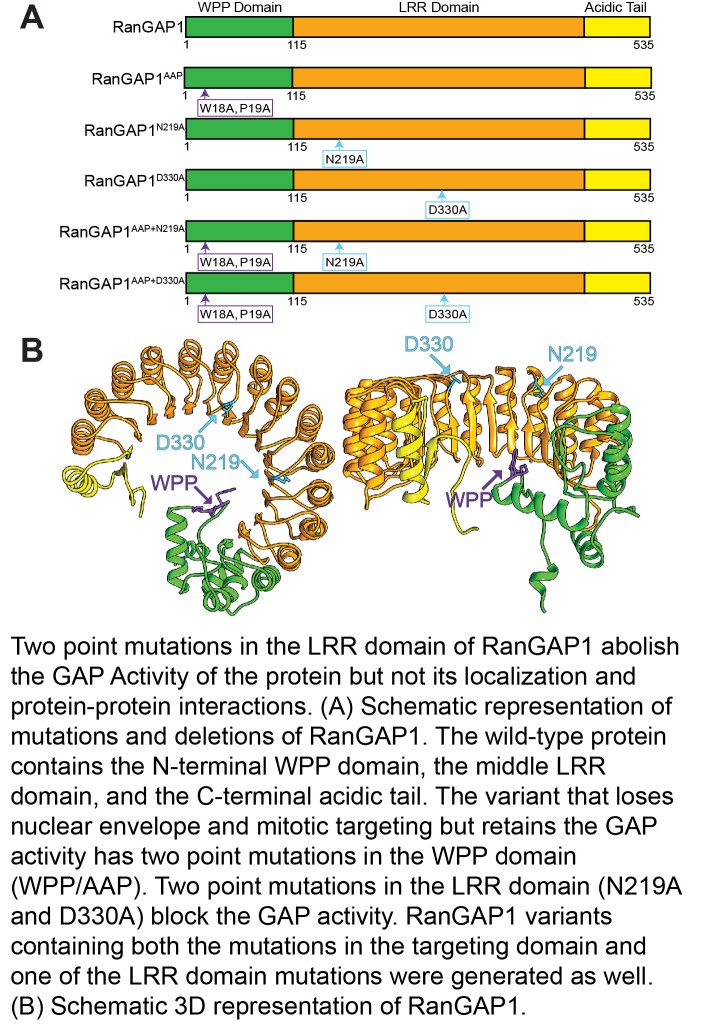

Ran is a small GTPase that is involved in determining the directionality of nucleocytoplasmic transport as well as in spindle organization, and postmitotic nuclear assembly. RanGAP is the GTPase activating protein of Ran. Both plant and animal RanGAP are anchored to the nuclear envelope where they hydrolyze RanGTP to RanGDP upon exit of transport complexes from the nucleus. We have discovered many years ago that plant RanGAP is anchored to the nuclear envelope by a different mechanism than animal RanGAP. Unlike vertebrate and yeast RanGAP, plant RanGAP has an N-terminal WPP domain, required for nuclear envelope association and several locations relevant during plant mitosis and cytokinesis. We have recently explored the relevance of this anchoring, as well as of the GTP hydrolysis activity of RanGAP, for a variety of plant developmental functions. We have shown that plant development is differentially affected by RanGAP mutant allele combinations of increasing severity and requires the GAP activity of RanGAP, while the subcellular positioning of RanGAP is dispensable. In addition, our results indicate that nucleocytoplasmic trafficking can tolerate both partial depletion of RanGAP and delocalization of RanGAP from the nuclear envelope. The next question is what the nuclear-transport-independent activity of plant RanGAP is and for what (currently unknown) cellular process the different subcellular locations of the protein are required.

Key reading:

Boruc, J.*, Griffis, A.H.N.*, Rodrigo-Peiris, T., Zhou, X., Tilford, B., Van Damme, D., and Meier, I. (2015) GAP Activity, but Not Subcellular Targeting, Is Required for Arabidopsis RanGAP Cellular and Developmental Functions. The Plant Cell 27 (7) 1985-1998. (* joint first authors).

Xu XM, Zhao Q, Rodrigo-Peiris T, Brkljacic J, He CS, Mueller S, Meier, I (2008) RanGAP1 is a continuous marker of the Arabidopsis cell division plane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105(47):18637-42.

Zhao, Q*, Brkljacic, J*, and Meier, I (2008) Two distinct, interacting classes of nuclear envelope-associated coiled-coil proteins are required for the tissue-specific nuclear envelope targeting of Arabidopsis RanGAP. Plant Cell 20, 1639-1651 (* joint first authors).

Xu X, Meulia T and Meier I. (2007). Anchorage of Plant RanGAP to the Nuclear Envelope Involves Novel Nuclear-Pore-Associated Proteins. Curr Biol. 17: 1157-1163.

Rose, A. and Meier, I. (2001). A domain unique to plant RanGAP is responsible for its targeting to the plant nuclear rim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 15377-15382.

3. Nucleocytoplasmic Trafficking

We study the role of individual nuclear pore proteins in how macromolecules are transported in and out of the plant nucleus. Currently, we are focusing on the nucleoporin NUA, a large coiled-coil protein predicted to reside at the nuclear pore basket. NUA is required for normal plant growth and development and for mRNA export from the nucleus. In NUA mutants, there is also a defect in the homeostasis of protein sumoylation. We address the role NUA plays in these different processes, and want to discover how they are molecularly connected.

Key reading:

Zhou, X., Boruc, J., and Meier, I. (2013). The Plant Nuclear Pore Complex — The Nucleocytoplasmic Barrier and Beyond. In Annual Plant Reviews (John Wiley & Sons Ltd), pp. 57-91.

Meier, I. (2012). mRNA export and sumoylation—Lessons from plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 1819, 531-537.

Ding, D., Muthuswamy, S., and Meier, I. (2012). Functional interaction between the Arabidopsis orthologs of spindle assembly checkpoint proteins MAD1 and MAD2 and the nucleoporin NUA. Plant Mol Biol 79, 203-216.

Boruc, J., Zhou, X., and Meier, I. (2012). Dynamics of the Plant Nuclear Envelope and Nuclear Pore. Plant Physiology 158, 78-86.

Muthuswamy, S., and Meier, I. (2011). Genetic and environmental changes in SUMO homeostasis lead to nuclear mRNA retention in plants. Planta 233, 201-208.

Meier I & Somers DE (2011). Regulation of nucleocytoplasmic trafficking in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 14(5):538-546.

Xu X, Rose A, Muthuswamy S, Jeong S-Y, Venkatakrishnan S, Zhao Q, and Meier I. (2007). NUCLEAR PORE ANCHOR, the Arabidopsis Homolog of Tpr/Mlp1/Mlp2/Megator, is Involved in mRNA Export and SUMO Homeostasis and Affects Diverse Aspects of Plant Development. Plant Cell 19: 1537-1548

Other expertise and hibernating projects:

Venkatakrishnan S, Mackey D, & Meier I (2013) Functional Investigation of the Plant-Specific Long Coiled-Coil Proteins PAMP-INDUCED COILED-COIL (PICC) and PICC-LIKE (PICL) in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 8(2):e57283.

Calikowski, T., and Meier, I. (2006). Isolation of Nuclear Proteins. In Arabidopsis Protocols, J. Salinas, and J. Sanchez-Serrano, eds. (Humana Press), pp. 393-402.

Rose A, Schraegle SJ, Stahlberg EA and Meier, I (2005). Coiled-coil protein composition of 22 proteomes – differences and common themes in subcellular infrastructure and traffic control. BMC Evol. Biol 5:66.

Rose, A., Manikantan, S., Schraegle, S., Maloy, M., Stahlberg, E. and Meier, I. (2004). Genome-wide Identification of Arabidopsis Coiled-coil Proteins and Establishment of the ARABI-COIL Database. Plant Physiol. 134:927-939.

Rose, A., and Meier, I. (2004). Scaffolds, levers, rods and springs: diverse cellular functions of long coiled-coil proteins. CMLS, Cell Mol Life Sci 61, 1996-2009.

Calikowski, T.T., Meulia, T., and Meier, I. (2003). A proteomic study of the arabidopsis nuclear matrix. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 90, 361-378.

Functional Organization of the Plant Nucleus. Plant Cell Monographs. Meier, Iris (Ed.); Springer, Heidelberg, 2009.

Merchant SS, Prochnik SE, Vallon O, et al. The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science. 2007 Oct 12;318(5848):245-50.

Meier, I. (2005). Global plant biotechnology and the need for an educated public. Minerva Biotecnologica 17, 21-31.