Summary by Alison Mulh:

Dances With Wolves is a Western film told from the point of view of Lieutenant John Dunbar, portrayed by Kevin Costner. It chronologically follows the life of Lieutenant Dunbar as he is assigned to Fort Sedgwick and arrives to find it abandoned. He forms a close bond with a group of nearby Sioux Indians and eventually assimilates into their tribe. Often there are voice overs that reflect what Dunbar is writing in his journal and provide narration for the events in the movie. His journal is one of the main narrative tools used in the film. Other characters, like Stands With A Fist, Kicking Bird, and Wind In His Hair, are just as important in progressing the story and showing how Dunbar had to earn the trust of the Sioux.

The film begins with Lieutenant Dunbar on an operating table with an injured leg. Rather than staying for treatment, Dunbar returns to the battlefield where he helps his fellow Union soldiers to win a battle against the Confederates. Dunbar is transferred to Fort Hays where he requests to go to Fort Sedgwick to fulfill his desire to see the frontier. He arrives to find it abandoned, but elects to stay to fix it up. A group of Sioux frequently try to steal his horse, Cisco. Eventually, Dunbar decides to go to the Sioux himself, but on the way finds an injured woman, who he later finds out is called Stands With A Fist.

The movie continues with meetings between Dunbar and the Sioux where they share parts of their lives with the other and learn to trust one another. Throughout all this, Dunbar keeps a record of their interactions in his journal where he talks of his feelings and frustrations about these meetings. When he wakes one night to the sound of a buffalo herd, Dunbar immediately mounts Cisco and rushes to the Sioux to let them know. He joins the hunt, but when it is over finds himself missing their company. He offers his assistance again when the Pawnee attack, and gives them with the extra guns from Fort Sedgwick.

John Dunbar, now called Dances With Wolves (after he is seen dancing around a fire with his camp companion, a white wolf called Two Socks) marries Stands With A Fist and agrees to stay with the Sioux he has befriended as they migrate to their winter camp. Before he can leave, he decides to return to the Fort to retrieve his journal only to find it now occupied by Union soldiers. Dunbar, now appearing like an Indian, is taken as a prisoner by the soldiers. Eventually, with the help of the Sioux, he is freed and reunited with Stands With A Fist. The two decide to go off on their own, as Dunbar knows the Army will come after him for the murders of the soldiers. The movie ends with scrolling text on the screen describing how thirteen years later, the last of the free Sioux surrendered, and the life of the American frontier was over.

Critical Appraisal by Jim Hardwick and Eddie Rice:

The general intent of Dances with Wolves is to provide an often uncomfortable perspective of the history of the United States’ expansion west along the American frontier. Broadly, western films in the past held European settlers as well as American Soldiers in high esteem to justify the significance of America’s destiny to traverse the continent and create a New World. Dances with Wolves does its best to pivot that angle in the opposite direction, shedding light on the reality of the multitude of forces which Native Americans were required to fair against, while also humanizing the people and their lifestyle countering the frequent savagistic depictions. The relationship forged and strengthened between Lieutenant John Dunbar and the nearby Sioux tribe reinforces this alternate portrayal of Natives. Though adolescents of the tribe initially attempt to steal Dunbar’s only horse, when the two parties make official contact an ironclad semblance of trust and respect for each other emerges.

As the film evolves, John Dunbar becomes a dependable ally and friend to the Sioux people. Once the communication gap is bridged by Stands with a Fist, the friends from different worlds diligently attempt to make sense of the other’s ways of life, as well as their intentions. John Dunbar is reluctant to answer the wave of questions about the imminent movement of white people into their lands, but nonetheless attempts to aid the Native peoples as earnestly as possible, as he grows to be affectionate to the Sioux culture and simplicity of life. Dunbar admires their unwavering commitment to community and family, while resisting material temptations, a trait which is idiosyncratic to the worldview of Anglo-American settlers which are inbound. Settlers felt that this way of life was distasteful, as the dominant view pushing them onto the frontier was the belief that they were not their brother’s keeper and that no one should interrupt the destiny for the ritualistically independent lives they were forging.

What also adds to the historical accuracy of this film is the way in which Kevin Costner and Michael Blake portray the Sioux tribe in the film as neither a typical depiction of hostile “savages” nor weak, completely peaceful people of the land. The Native Americans as well as their white settler counterparts are humans with both virtues and vices. Native groups fought over land and territory between each other for hundreds of years even before the start of colonisation in the United States. Like their European counterparts, war was a necessary part of life in order to self preservate both their cultures as well as customs. When confronted with simply another group encroaching on their territory, they put forth the same attitudes that historically we know to be accurate of the ways in which Native Americans conducted war. Adding to this, it reinforces some of the ironic reasoning from Dunbar and his colleagues. Dunbar for example listens to and believes for the most part individuals references to the Sioux in this film as “warlike savages”. Furthermore, reinforcing this irony is the fact that Dunbar himself is a soldier of the most “savage” variety, rushing into battle mortally wounded and still continuing to fight in what is also one of the most savage wars in American history.

Suggested Readings by Luke Balizet:

Unlike some of the other American history movies we have watched this semester, namely, Black Robe, The Crucible, A Quiet Passion, and 12 Years a Slave, Dances with Wolves is not based on any historical person or event, only citing real people, places, and ideas as loose inspirations. Because of this, the tasks of assessing the historicity of Dances with Wolves as well as researching the true-to-life elements of the film are rendered less than trivial compared to the previous movies mentioned. Nonetheless, the function of creating a tight canon of related historical works and modern assessments relating to the subjects of Dances with Wolves remains critical in the assessment of the film as a whole and as a vessel on the journey towards true understanding (if there even is such a thing). We will describe several sources that we believe deserve a position in this canon.

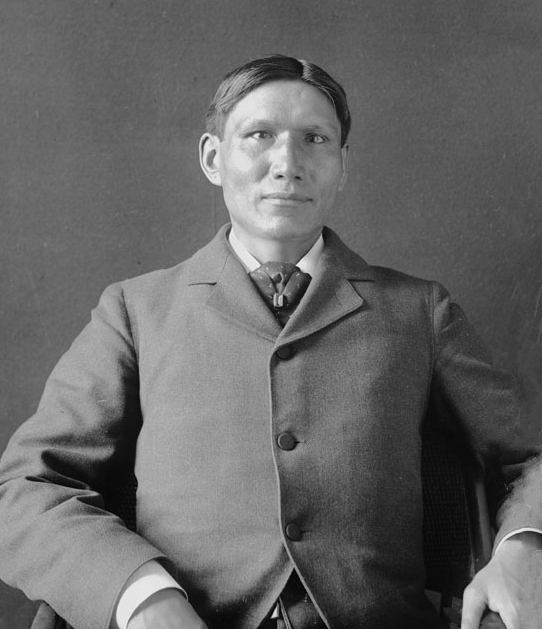

Source #1: Memories of an Indian Boyhood by Charles Eastman

Charles Eastman (1858–1939) was a Sioux physician famous for his 20th century writings on the Native American experience in America. Eastman was born and raised in the Santee Dakota culture and subsequently integrated into white American society, being educated at Dartmouth College and Boston University. Eastman traveled to South Dakota after his education to work and practice for the Bureau of Indian Affairs at both the Pine Ridge and Crow Creek Reservations. His claim to fame were his first-hand accounts and written experiences of his Sioux upbringing and his American-educated life in the larger white society. He was considered a contemporary expert on Indian affairs and culture and wrote over 10 books. The particular book we are interested in as it relates to Dances with Wolves is his childhood memoir Memories of an Indian Boyhood. In this book, Ohiyesa (Eastman) recounts the first fifteen years of his life as a Dakota Sioux in the late 19th century, almost exactly when Dances with Wolves takes place. The book covers everything from the mundane, day-to-day activities of his people all the way to the direct existential threats of the American military and the impending railroads. This first-hand account of life as a Sioux provides deep insight into the idiosyncrasies of the Sioux and acts as an indirect guide from an acclaimed expert as to what Dances with Wolves did and did not get right in regards to Sioux culture. In contrast to most primary sources of the time, this source is not from the perspective of a white person and because of this, it is probably in the vein of the most important source to critically analyze Dances with Wolves with.

Source #2: Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri by Edwin Thompson Denig

Edwin Thompson Denig (1812–1858) was a white, American fur trader who worked primarily in the “upper Missouri”. Denig headed the American Fur Company’s post at Fort Union, where he was also married to the daughter of an Assiniboine chief and wrote extensively about the Plains Indians of the surrounding areas. Perhaps his most famous work, Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri records Denig’s first-hand observations of Sioux, Arickaras, Assiniboines, Crees, and Crows customs and culture. Denig is considered an important ethnographer of the Plains Indians, and although an outside, white observer, his recordings remain an invaluable resource in the historical documentation of these peoples’ ways and cultures. Being a fur trader, questions of bias towards economic gain are rightfully warranted when reading such accounts, but the critical examination of how this work sees American Indians is an excellent companion to the exact same examination in Dances with Wolves.

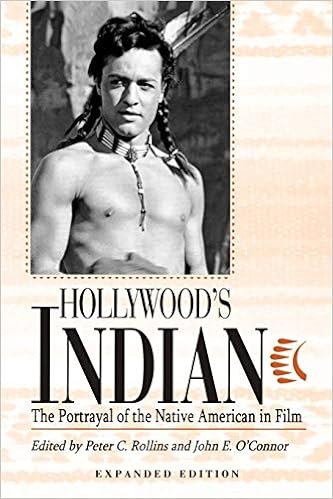

Source #3: Hollywood’s Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film by Various Authors

The previous 2 sources we have examined are primary sources from the era in which Dances with Wolves takes place—one written by a Sioux Indian and the other written by a white fur trader—but the following source is a departure from this pattern of primary sources, shedding some modern light and interpretation on the film industry’s long history with Native Americans. Hollywood’s Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film is a 2011 collection of essays by 17 scholars discussing the history of the portrayal of Native Americans in film. Whereas Eastman and Denig’s first-hand accounts help us critically analyze the specific historicity of Dances with Wolves and perhaps some of its historical prejudices, Hollywood’s Indian is less concerned with micro-level historical accuracy and more concerned with a macro-level analysis of the film industry as a whole using specific examples such as Dances with Wolves. One aspect of Dances with Wolves specifically that the collection rightfully points out is that the film may be considered a Revisionist Western and be one of the first large scale portrayals of American Indians as whole people—kind, humorous, loving, awkward, violent, deeply flawed, etc.—but at the end of the day, its protagonist is still a white male, who could be seen as a “white savior”. What does this say about us as a society and how we see the Sioux people? It’s not enough to know the history of an event or people, we also have to understand how that event or people has been portrayed historically and what that says about the portrayers and portrayees. Hollywood’s Indian provides much needed insight into this complex discussion.

DWW-awesome job! I like the analysis and the sources (although links to them would be nice for the reader.). I would like to have seen you bring in the reading from Paul Chaatsmith from earlier in the term. Also, some historians have been critical of the movie as using classic western stereotypes–the Pawnee, the Sioux’ other antagonists in the movie, are portrayed as dark-skinned and more “savage.” Also, the idea that only about five Sioux plus our hero were left in the end is a bit of an overstatement and plays into the disappearing Indian trope.