As other colleagues have previously posted in this blog, un-immersive fieldwork1 has endless options that can unravel new ideas and research approaches. Inspired by Max Woodworth’s re-visitation2 to his photographic archives, I started looking back at my pictures of Bolivia – both my native land and my dissertation study site. Ever since I moved to the US in 2016, I have been able to go back to my home country twice per year, and only for a few weeks each time. This means that my photographic collection is intrinsically incomplete chronologically. However, when re-imagined as scattered pieces of a puzzle and integrated with images from other sources, it is possible to recognize some intriguing “before-and-after” stories. These other sources are various and somewhat unorthodox: Google Earth imagery, online newspapers, sometimes even pictures from unrelated trips. Capturing either the aftermath scenes, or unplanned “beginnings,” these images accompanied my journeys researching mountain ecosystems in Bolivia. The stories that these images narrate remind us that the impacts of climate change are true and tangible even in very short intervals of time.

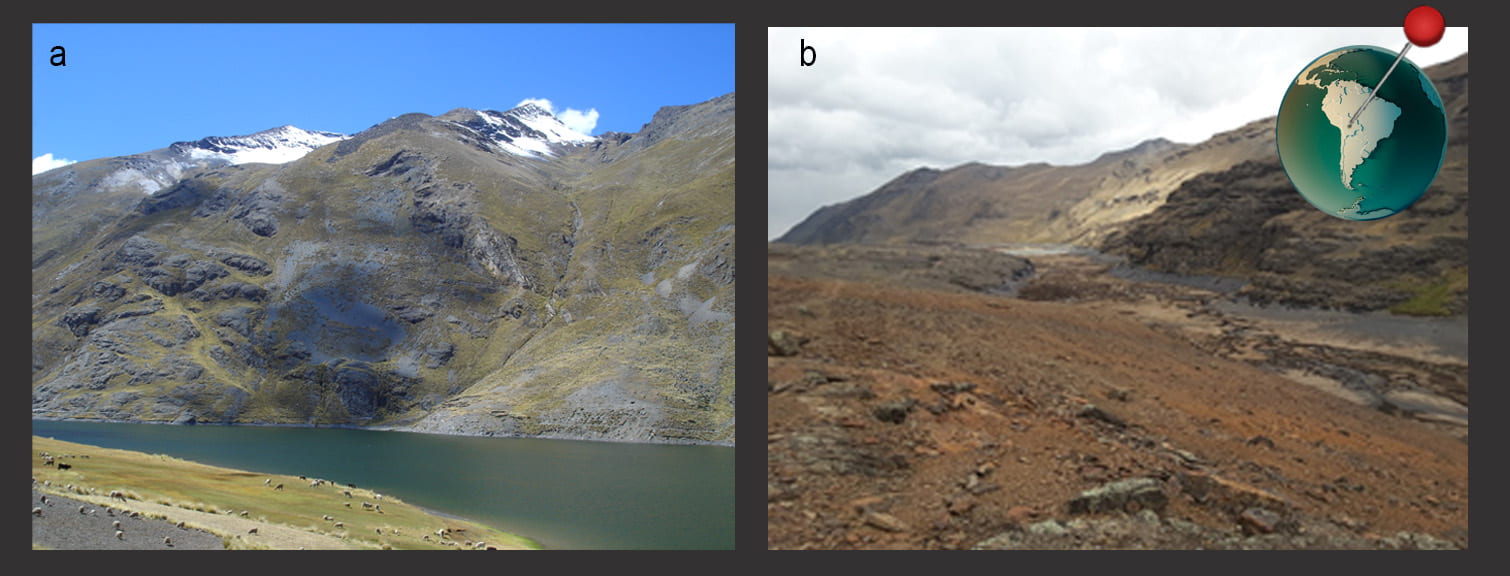

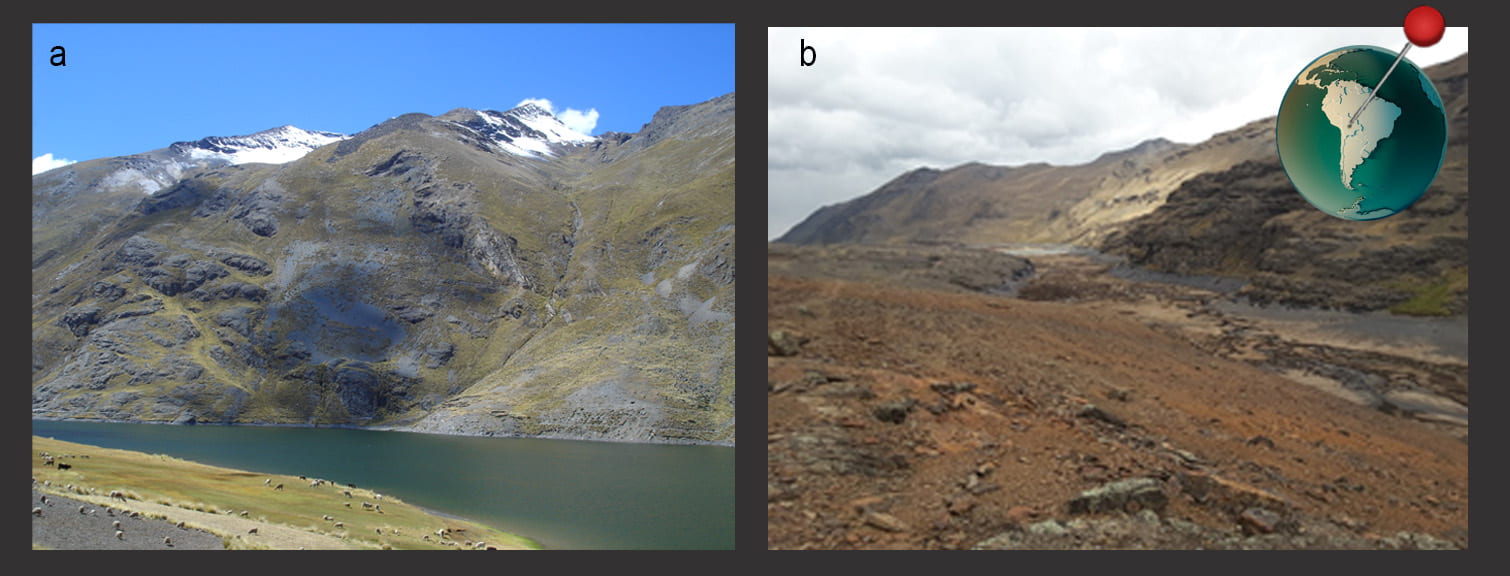

For example, in July 2016, I joined my co-advisor Karina Yager from Stony Brook University on a few trips to the Bolivian Altiplano. We were surveying potential study areas for future research on bofedales (high altitude wetlands of the Andes). While in the Hampaturi Valley, we observed the surroundings of a water reservoir and took some casual pictures of the site (Figure 1a). What I did not know at that moment is that a few months later, the drought caused by the 2015-2016 El Niño would completely dry out the reservoir. When I came back to Bolivia in December that year, I was able to see it with my own eyes. The scene was heartbreaking. Not only were a quarter of million people of La Paz left without water service for months, the vegetation was also dead, the birds were gone, and the dry bottom of the reservoir revealed something that surprised me: the reservoir for the city’s drinking water was built over a former bofedal (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Aiuan Kkota reservoir in July (a), and December (b), 2016. The reservoir dried out as a consequence of the El Niño 2016. Photo credits: Gabriel Zeballos

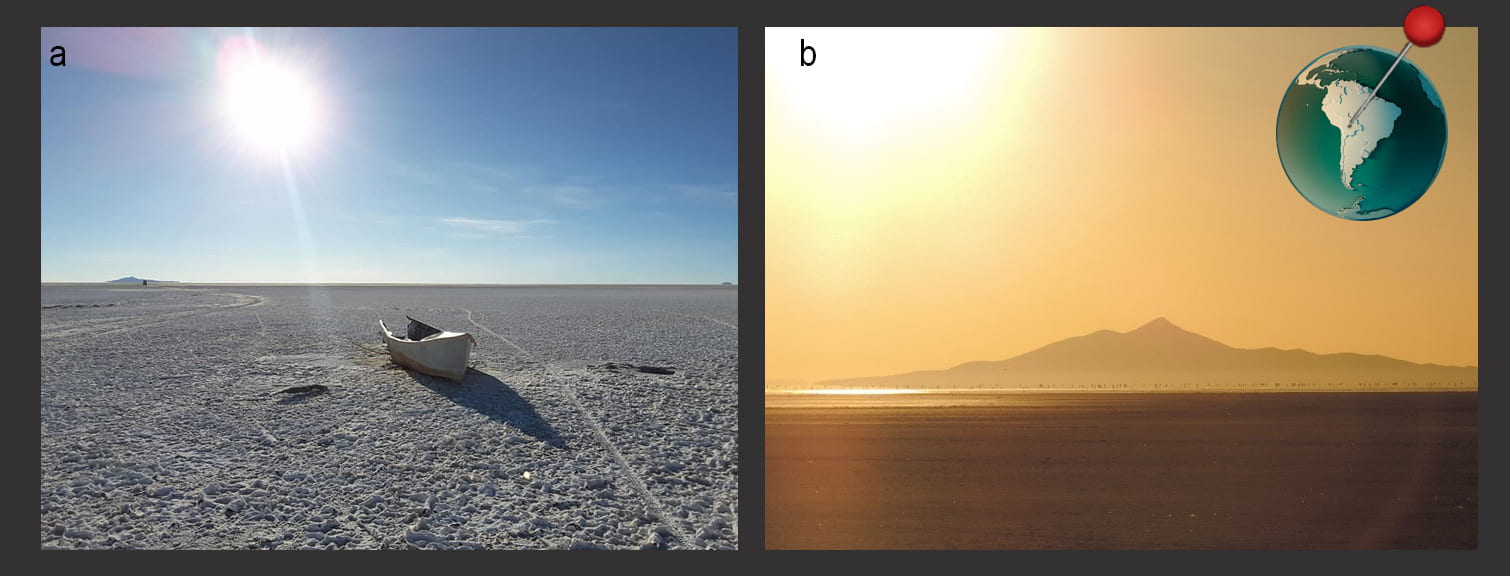

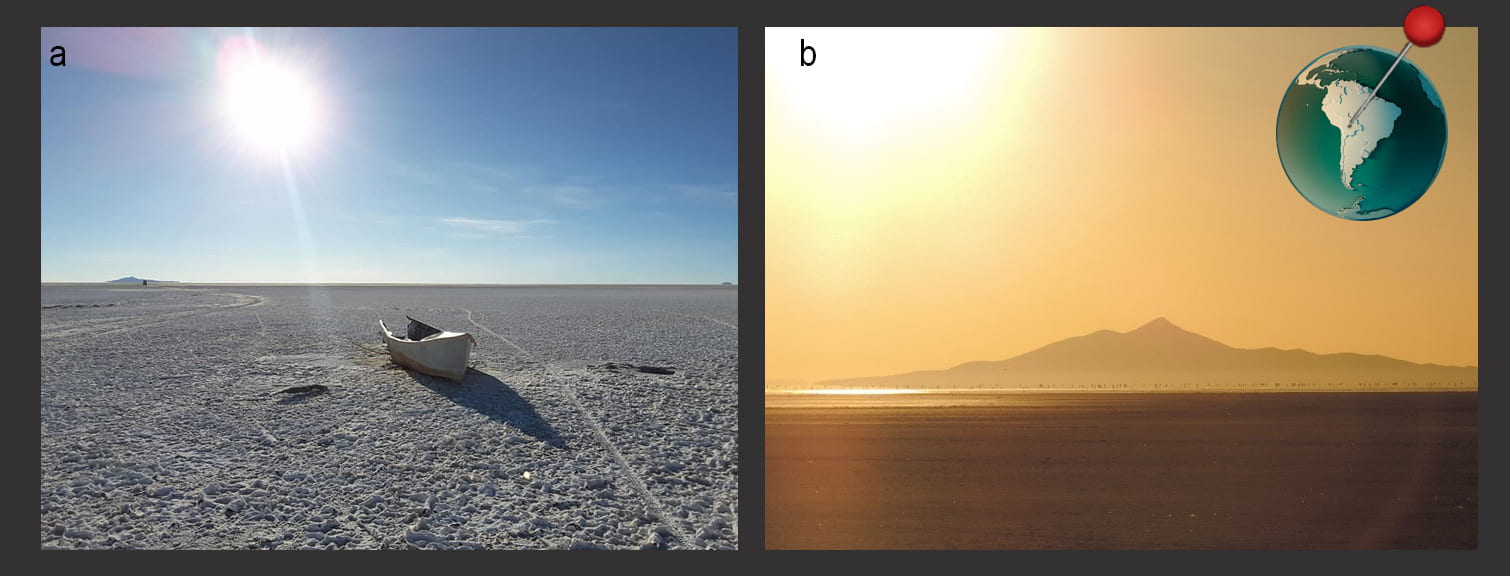

That was not the only body of water that dried out that year. The second largest lake in Bolivia, Lake Poopo, also disappeared. I visited the lake from the coastal town of Huari on June 2017. Despite some recuperation of the water levels in the previous months, I could observe the abandoned boats (Figure 2a). The soil was strikingly salty and the bottom was dry as far as the eyes could reach. It reminded me of the pictures I had seen from the Aral Sea. In August 2019, I went back to Huari. I was on a fieldtrip to the Bolivian Southern Altiplano. I took a short detour from my way. I needed to go back to the same place where I saw the abandoned boats in 2017. This time there were no boats, but also, almost no water. My powerful camera was able to capture some water bodies far on the horizon (Figure 2b). Flocks of flamingos were present. To see wildlife always warms the heart, although I knew that the economic activities of the anglers were never going to recover to levels of the past. The former anglers probably had migrated to other regions already by that time. They are climate refugees.

Figure 2. Lake Poopo in June 2017 (a) and August 2019 (b). The second largest lake in Bolivia dried out several times in the past five years. Photo credits: Gabriel Zeballos

Two thousand nineteen was also a hard year for my hometown, La Paz. In January, a landslide wiped out an entire segment of the Llojeta neighborhood, a sector built a couple of decades ago over a former waste landfill. Even 11 months later, when I took a picture from a cable car, the area still looked destroyed and under risk of collapse. An image from the History tool from Google Earth can give a better idea of how Llojeta appeared before the landslide (Figure 3a). It is not news that Google Earth has this useful application to view several older images of scenes, but to be able to capture a picture from the terrain gave me a better idea of the scale and magnitude of the event (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Llojeta neighborhood in early January 2019, before the landslide (a), and December 2019 (b). The red outline shows the sector destroyed by the massive landslide. Photo credits: a) Google Earth, b) Gabriel Zeballos.

Later that year, the Amazon Rainforest from Bolivia and Brazil suffered one of the worst wildfires in recent history. I happened to visit one of the most impacted sites a few months before the beginning of the wildfires. The site of the picture is called the Serranía de Chochis. Besides its natural beauty and biological richness, this region belongs to one of the UNESCO’s World Historical Heritage sites: The Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos. The image on the left (Figure 4a) is the one I took with my cellphone camera in early January 2019. The image on the right belongs to an online newspaper (opinion.com.bo) (Figure 4b). That is what was left in late September 2019.

Figure 4. Serranía de Chochis in January (a) and September (b), 2019. The wildfires destroyed over 6 million hectares only in Bolivia. Credits: a) Gabriel Zeballos, b) Gabriel Zeballos based on a picture printed in Periódico Opinión.

In the early nineteenth century, the French explorer Alcides D’Orbigny commented about his travels through South America4:

“If the Earth disappeared, leaving only Bolivia, all the products and climates of the world would still exist. Bolivia is the planet’s microcosm. Due to its height, its climate, and its infinite variety of geographical nuances, Bolivia becomes the synthesis of the world.”

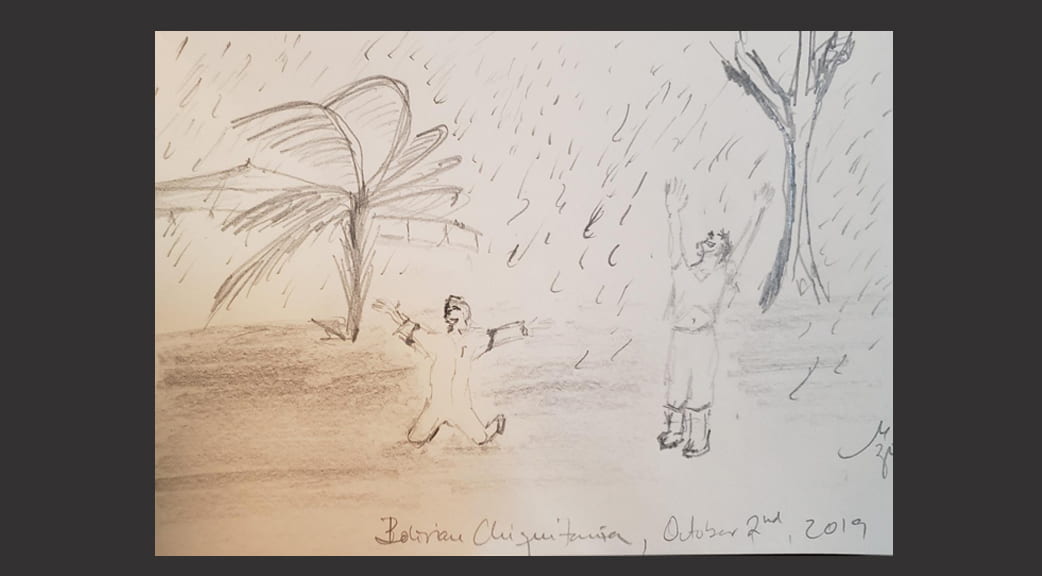

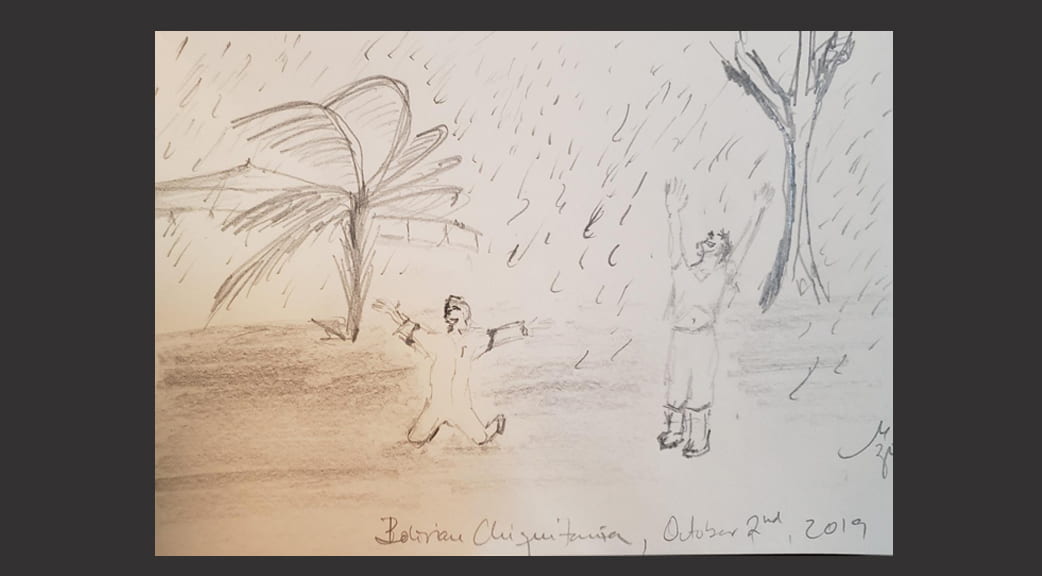

For almost two centuries, D’Orbigny’s descriptions and travel logs were the single piece that portrayed Bolivia’s natural and cultural richness5. Today, his images comprise a new puzzle that is excruciating to fill. A puzzle where Bolivia is still a microcosm of the Earth. Only that this time, Bolivia is becoming the synthesis of the environmental degradation and global climate change that affects the world at large. Can we, as a global society, be an active part of the restoration of our common house? Without really knowing the answer, it inspires me to look at the next image. It is a rendering from a picture of the day in which the rainfall extinguished the wildfires in the Eastern Bolivian Forest. The firefighters’ joy says it all (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bolivian firefighters and volunteers celebrate under the rainfall in September 2019. Drawing: Gabriel Zeballos based on a picture published on Pagina Siete

Post Scriptum

I finished writing this text in June 2020. However, until the publication of this post, I did not get response from the mentioned newspapers in order to get the copyrights of the referred pictures (Figures 4 and 5). That is why I sketched the images instead. Interestingly, by drawing the gray landscape and then the people’s joy, I unexpectedly felt an abstract closeness to my homeland albeit the abstract and real distance. Un-immersive work is not any simpler than an in-situ study but it is just different. Thus, combining both it is possible to add new dimensions of understanding to one’s research.

Gabriel Zeballos, Ph. D. Candidate

Department of Geography,

The Ohio State University

Citations:

- Kendra McSweeney: Un-immersive-fieldwork

- Max Woodworth: Re-visiting the Field Through Old Fieldwork Photos

- https://www.opinion.com.bo/articulo/incendios-forestales/gobierno-eval-uacute-prioridad-tareas-control-definitivo-fuego-chiquitania/20190904104500725262.html

- Díaz Arguedas J. Alcide d’Orbigny: Estudios sobre la geología de Bolivia. El naturalista francés Alcide d’Orbigny en la visión de los bolivianos. 2002:195-209.

- Aguirre RDA. Alcide d’Orbigny en la vision de los bolivianos. Bulletin de l’Institut francais d’etudes andines. 2003 (32 (3)):467-477.

- https://www.paginasiete.bo/sociedad/2019/10/2/lluvias-en-mas-de-municipios-llevan-esperanza-la-chiquitania-232865.html?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=facebook#!