In today’s society, schooling is becoming more stern, meaning we have many more requirements to reach so we are focused on getting there. A “problem” you could say that is holding educators back from reaching those requirements are “special need students” not because teachers are against the idea of mental disabilities, but teachers need to reach many state standards in order to allow their students to pass state testing making their evaluations better. Special needs students have many things that come along with helping them in a school. They need an aid to keep them under control, they need further explaining of harder concepts, and they need more attention than most students because they need a very good education. Teachers don’t have time to do all of this just for one student in their class so they make their students take an evaluation test to see if they qualify for public school teaching or a special needs education academy that has trained specialists for these students.

Case Law involving Special Needs and Student’s With Disabilities

“Children with disabilities require special education and related services that are as diverse as the individual children themselves”.

General Education Teacher Preparation

Research has repeatedly shown that general education teachers are not properly trained to help students with mild disabilities settle and succeed in their classrooms.

Proper training in teacher training programs, consistent professional development courses, and time for effective collaboration with special education teachers would help teachers in raising their self efficacy tremendously in assisting special needs students in their classroom.

Research by DeSimone and Parmar (2006), interviewing middle childhood teachers showed that their pre service teaching programs did not adequately prepare them to work with students with learning disabilities. Preservice teaching programs including more content on learning disabilities and pedagogical practices for their students help teachers to feel confident in working with these diverse students.

However, traditional classroom coursework is not enough for preservice teaching programs. According to Jung (2007), students who underwent guided field experiences felt more confident in working with children with disabilities compared to those who only studied about special needs students in a traditional classroom. Students who take part in more field experiences where special education inclusion is successful feel more ready to use what they see in their own classes, therefore raising their self efficacy in addressing their needs.

Teachers also feel a lack of professional development in regards to assisting students with special needs. When teachers make adaptations for students in their classes with unique learning accommodations, such as IEPs, they benefit from consistent professional development courses that can help them with their instruction strategies. Research done by Kosko and Wilkins (2009) has shown that overall, teachers who receive more hours of professional development than those who don’t feel better equipped to adapt their teaching instruction for students with IEPs, especially when it pertains to the content that they teach. This applies to behavioral management as well. Research by Pindiprolu, Peterson, and Berglof (2007) shows that from the schools they surveyed throughout the Midwest, school personnel as a whole frequently expressed the desire for professional development in behavioral problems, FBAs, and inclusion. Results like these show that teachers are not prepared and trained to use intervention practices to help students adjust properly in the classroom and have better classroom management.

A lack of efficient collaboration between general education teachers and special education teachers may get in the way of providing quality education and making both teachers comfortable in working with their students. According to an analysis of preservice teachers by Da Fonte and Barton-Atwood (2015), these students discussed setting time to collaborate efficiently, closing gaps in content knowledge, and having proper communication as ways to better collaboration. Creating the time can be increasingly difficult for teachers as their responsibilities increase. When school personnel are able to create set times for collaboration and meetings for children with special needs, clear expectations can be set amongst the teachers to better prepare them to work with students with disabilities.

Gaps in content knowledge and proper communication are also obstacles that come in between effective collaboration. General education teachers are trained to teach their subjects at a specific age level. Meanwhile, special education teachers are prepared to carry out intervention techniques to students of many different age levels. These gaps can then make it difficult to understand the roles of the other. Thus, it is difficult to reach the needs of students with disabilities if the teachers do not have similar expectations.

Teacher Bias

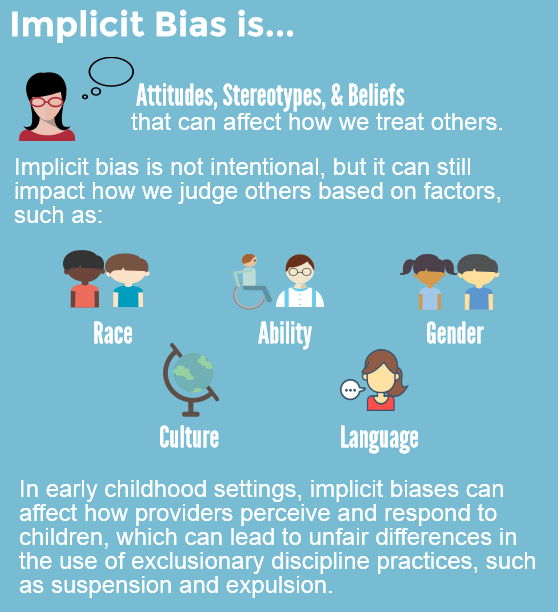

Studies have shown that there is teacher bias against students with disabilities, which is due to a number of factors. These factors include teachers exhibiting prejudice against students with special needs, how that prejudice affects those kids and the kids around them, what causes this prejudice and possible solutions to the issue.

Teacher bias is defined as an educator holding prejudice against certain students because of a specific identity those students have. One of the main factors in teacher bias against special needs kids is lack of preparedness. The teachers who have these students in their classrooms, more often than not, have not been properly trained to handle students with disabilities and the behaviors they may exhibit. Resources like IEPs exist in order to help the teacher understand what a disabled student is dealing with and what the teacher can and/or needs to do in order to accommodate them. However, IEPs are often not enough training on how to handle these kids, making it difficult on teachers, and parents as the amount of students with disabilities in a general classroom is only increasing.

According to a 2014 survey on teacher preparedness and attitudes toward students with disabilities in the science classroom, the percentage of disabled students spending most of their time in a general classroom rose from 45% to 61%. It is apparent that these students are being integrated into the regular classroom more and more. This same study explains how there is an extensive body of literature that has linked attitude and preparedness to positive, inclusive experiences for special needs students. When teachers feel more prepared to teach these students there is a better chance of those teachers being more inclusive and creating a positive environment. The study surveyed various science teachers, asking them specific questions about their experiences teaching students with disabilities. The study found that 59% of the teachers had taught students with learning disabilities at some point in their careers, 62% had taught students with emotional/behavioral disabilities and 58% had taught students on the Autism spectrum. With well over half of the participants reporting that they had taught students with some kind of disability, this is a clear indication of how easily prejudice can occur when so many teachers are interacting with special needs students and so many are often unprepared. Although 70% of the teachers surveyed reported that they had received training in some capacity, that still leaves 30% with absolutely no training whatsoever. Also, the question about training was not specific about what kind of training, resulting in most of that 70% citing on-the-job training as their only real edification in teaching these students. Only 42% reported college as a source of training and those teachers were mainly trained in inclusion, modifying lessons and legal concerns. (Kahn 2014)

Various studies have reported that when students with disabilities aren’t successful in the classroom, a big factor is teacher attitude and preparedness. Bias also affects the social life of the student, causing other non-disabled students to react similarly to the teacher. When a teacher has negative interactions with a disabled student and acts negatively toward them, other students are more likely to act the same way, especially in a classroom of younger kids who are more easily influenced. According to a 2006 study that explored how children’s attitudes toward disabled children develop, kids from the age of 4 were able to notice negative behavior shown toward disabled children and in turn exhibited that same behavior toward those same children. (Han 2006)

Solutions You Can Employ

- Promote Open and Honest Dialogue Among Staff and Co-workers

- Identify Training Needs

- Create Formal Policies and Procedures

- Express Gratitude and Acknowledge Progress

This list was taken from https://preventexpulsion.org/1g-provide-professional-development-and-ongoing-support-for-all-program-staff-on-culturally-responsive-practices-and-implicit-bias/.

Special Needs Schools & Special Needs Factors

Special Education is a very hard subject to grasp, especially since it holds so many factors and possibility. Many schools do not have the right resources to teach children with disabilities, but on the other hand, those schools that do are substantial. Franklin county employs trained staff for special education and has them take an evaluation test which tests over if they are gifted enough to stay in the school location that they are in, or if they need more than a public school for their grade school career. Now believe it or not, the cost of educating a special needs student is way more expensive than one may think. www.nea.org tells us in the article of “Background of Special Education and the IDEA” with the 2004 IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) reauthorization bill, that one special needs students costs alone $7,552 and their education costs an additional $9,369 for a total amount of $16,921. Even though this article tells us that the federal law has included a commitment to pay 40% of the average cost of a special needs student, that still leaves $6,768.40/year for every student. Compare that to a college tuition monthly payment here at Ohio State is about $6,500. Now remember, that’s just the cost of one student, we have no idea how much each student altogether is per year.

We learn about even more outrageous costs of special education in the U.S in the article from Chasson, G. S., Harris, G. E., & Neely, W. J. (2007). They tell us about the costs of special education and how they can range from $11,000 to $60,000 per child per year with autism disability sickness, but it also takes 6-7 therapists per student in some schools for this disability.

Causton-Theoharis, J., & Theoharis, G. (2008) & Beyer, B., & Johnson, E. S. (2014), both tell us about the special programs in which are recommended in schools if a student is tested and seems like they would be better off if they were put into a more focused and helpful program. Although this may seem like a good idea, this can make your classroom very excluded and make your special education students feel alienated to the rest of the class.

Kutash, K., & Duchnowski, A. J. (2004), say that special education programs are actually more successful in an urban area because of how unfocused the school is on creating the most elite students. Another popular thing that helps special education become such a strong community is bringing in the most newly trained specialists and therapists that understand how to care for and educate these students. Maheady, L., Harper, G. F., & Mallette, B. (2001), talk about how Peer Mediated Instruction and interventionists come in and help out teachers in the classroom. It is harder to allow for this in rural communities because having specialists like these in your classroom are considered a distraction and inconvenience because it slows the learning of other students.

Chang, Nicole. March 1, 2019, tells us about the top 10 schools that are most open to schools with disabilities especially physical. This is also a huge factor that plays into the special education needs, because many schools don’t recognize those students. Accessibility for someone with a physical disability is very difficult to cope with because many places aren’t accessible for these students.

Resources Both In and Out of the Classroom

Listed below are many great resources for parents, students, and teachers who have a child who may have a disability. These sources are great for those seeking more information on how to schedule an evaluation for their child as well as teachers who may have questions about a student having a disability. There are also many parent support groups as well, whether it is via their school district such as Columbus City Schools Parent Mentor Program, or even different websites that have online forums for parents to turn to for solace.

Education for Special Needs. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://cap4kids.org/columbus/special-needs-autism/education-special/.

IEP Parent Support. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://www.understandingspecialeducation.com/IEP-parent-support.html.

Private School and Special Education Services. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://www.understandingspecialeducation.com/private-school.html.

The Comfort Wall. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://www.understandingspecialeducation.com/comfort.html.

Understanding IEP Law and Special Education. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://www.understandingspecialeducation.com/IEP-law.html.

Understanding Special Education Funding. (n.d.). Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://www.understandingspecialeducation.com/special-education-funding.html.

Practical Book for Teachers- Murawski, W. W. (2010). Collaborative Teaching in Elementary Schools: Making the Co-Teaching Marriage Work! Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Book for Classroom Students- Clark, J. (2007). Ann Drew Jackson. AAPC Publishing.

Preventing Suspensions and Expulsions in Early Childhood Settings (n.d) Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://preventexpulsion.org/

Special Education Student Enrollment

In the 2017-2018 school year, Ohio’s students with disabilities accounted for 15.7% or 266,370 of the student population. The special education student enrollment table outlines this trend data in greater detail.

| 2015-2016 | 2017-2018 | |

| No Disability | 1,557,857 | 1,433,452 |

| Autism | 19.968 | 25,131 |

| Deaf/Blind | 38 | 68 |

| Deafness/Hearing Impairment | 1,863 | 2,153 |

| Developmental Delay | 2,526 | 7,081 |

| Emotional Disturbance | 14,979 | 15,340 |

| Intellectual Disability (Cognitive/MR) | 19,840 | 20,047 |

| Multiple Disabilities | 12,515 | 13,232 |

| Orthopedic Impairment | 1,324 | 1,532 |

| Other Health Impaired | 38,211 | 44,392 |

| Specific Learning Disabilities | 95,720 | 98,203 |

| Speech and Language Impairments | 25,243 | 36,691 |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 1,431 | 1,559 |

| Visual Impairments | 867 | 941 |

| TOTAL STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES | 234,525 | 266,370 |

| TOTAL STUDENTS | 1,792,382 | 1,699,822 |

| % OF TOTAL POPULATION | 13.08% | 15.7% |

Key Terms

The following formal definitions are from Understandingspecialeducation.com, a website dedicated to help understand the process of schooling for children with special needs.

504 Plan: | a plan developed to ensure that a child who has a disability identified under the law and is attending an elementary or secondary educational institution receives accommodations that will ensure their academic success and access to the learning environment.

Accommodations: Changes that allow a person with a disability to participate fully in an activity. Examples include, extended time, different test format, and alterations to a classroom.

Assessment or Evaluation: Term used to describe the testing and diagnostic processes leading up to the development of an appropriate IEP for a student with special education needs.

Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP): Special education term used to describe the written plan used to address problem behavior that includes positive behavioral interventions, strategies and support. May include program modifications and supplementary aids and services.

Designated Instruction Services (DIS): Instruction and services not normally provided by regular classes, resource specialist programs or special day classes. They include speech therapy and adaptive physical education.

Disability: Physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.

Extended School Year Services (ESY): An extended school year is a component of special education services for students with unique needs who require services in excess of the regular academic year. Extended year often refers to summer school.

Free appropriate public education (FAPE): | A cornerstone of IDEA, our nation’s special education law, is that each eligible child with a disability is entitled to a free appropriate public education (FAPE) that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet the child’s unique needs and that prepares the child for further education, employment, and independent living

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA): A problem solving process for addressing inappropriate behavior.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA): The original legislation was written in 1975 guaranteeing students with disabilities a free and appropriate public education and the right to be educated with their non-disabled peers. Congress has reauthorized this federal law. The most recent revision occurred in 2004.

Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE): A school district is required by law to conduct assessments for students who may be eligible for special education. If the parent disagrees with the results of a school district’s evaluation conducted on their child, they have the right to request an independent educational evaluation. The district must provide parents with information about how to obtain an IEE. An independent educational evaluation means an evaluation conducted by a qualified examiner who is not employed by the school district. Public expense means the school district pays for the full cost of the evaluation and that it is provided at no cost to the parent.

Individualized Education Program (IEP): | a plan or program developed to ensure that a child who has a disability identified under the law and is attending an elementary or secondary educational institution receives specialized instruction and related services.

Least Restrictive Environment (LRE): The placement of a special needs student in a manner promoting the maximum possible interaction with the general school population. Placement options are offered on a continuum including regular classroom with no support services, regular classroom with support services, designated instruction services, special day classes and private special education programs.

Private School: There are new laws regulating the rights of students with disabilities whose parents place them in private schools. When a student is enrolled in private school and has academic difficulties, the school where the student attends needs to inform the parent and the local public-school district of the student’s difficulties. The district of residence may assess the student to determine if the student qualifies for special education. If they do qualify, the district of residence is responsible for writing an Individualized Education Plan.

Teacher Bias: The act of a teacher holding a personal and often unreasoned judgement against a student because of specific identity that student holds.

Transition IEP: IDEA mandates that at age 16, the IEP must include a statement about transition including goals for post-secondary activities and the services needed to achieve these goals. This is referred to an Individual Transition Plan or (ITP).

IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act): A law that makes available and free appropriate public education to eligible children with disabilities throughout the nation and ensures special education and related services to those children.

Peer Mediated Instruction– Newly Trained students in the special education major that come into classrooms to help with students with a mental disability.

References

A.HurwitzMD, K. (2008, August 23). A Review of Special Education Law. Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0887899408003032?token=C492A055E39669323F94n.d.EFCD6D666DD43D05C344C3D58B44C00D05F774566CBD7B167E8C3E27DE23F5F0BCFC8861E.

American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD). (n.d.). Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://cap4kids.org/columbus/216931371/.

Association for the Developmentally Disabled (ADD) & Hattie Larlham Central Ohio Services. (n.d.). Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://cap4kids.org/columbus/600241528/.

CADRE (The Center for Appropriate Dispute Resolution in Special Education). (1970, January 1). Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://www.cadreworks.org/.

Clark, J. (2007). Ann Drew Jackson. AAPC Publishing.

Da Fonte, M. A., & Barton-Arwood, S. M. (2017). Collaboration of general and special education teachers: Perspectives and strategies. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(2), 99-106.

Dalton, M. A. (2002). Education rights and the special needs child. Retrieved November 2, 2019, from Education rights and the special needs child.

DeSimone, J. R., & Parmar, R. S. (2006b). Middle school mathematics teachers’ beliefs about inclusion of students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 21(2), 98–110.

Fabre, T. R., & Walker, H. M. (1987). Teacher Perceptions of the Behavioral Adjustment of Primary Grade Level Handicapped Pupils Within Regular and Special Education Settings. Rase. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258700800506

Gay, G. (2002). Culturally responsive teaching in special education for ethnically diverse students: Setting the stage. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 15(6), 613–629. doi: 10.1080/0951839022000014349

Girma, Haben. Why I work to remove access barriers for students with disabilities, TEDXBaltimore. 28 February, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mvoj-ku8zk0.

Gravois, T. A., & Rosenfield, S. A. (2006). Impact of Instructional Consultation Teams on the Disproportionate Referral and Placement of Minority Students in Special Education. Remedial and Special Education. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325060270010501

Han, J., Ostrosky, M. M., & Diamond, K. E. (2006). Childrens Attitudes Toward Peers With Disabilities: Supporting Positive Attitude Development. Young Exceptional Children, 10(1), 2–11. doi: 10.1177/109625060601000101

Hegarty, Seamus. “Education of Children with Disabilities.” Special Needs Education, Aug. 2019, pp. 16–28., doi:10.4324/9780203080313-2.

Jung, W. S. (2007). Preservice Teacher Training for Successful Inclusion. Education, 128(1).

Kahn, S., & Lewis, A. R. (2014). Survey on Teaching Science to K-12 Students with Disabilities: Teacher Preparedness and Attitudes. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 25(8), 885–910. doi: 10.1007/s10972-014-9406-z

Kosko, K. W., & Wilkins, J. L. (2009). General Educators’ In-Service Training and Their Self-Perceived Ability to Adapt Instruction for Students with IEPs. Professional Educator, 33(2), n2.

Krakower, B., & Plante, S. L. (2015). Using Technology to Engage Students With Learning Disabilities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Lin, M., Lake, V. E., & Rice, D. (2008). Teaching Anti-Bias Curriculum in Teacher Education Programs: What and How. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(2). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23479231.pdf?casa_token=8iB27QQaip4AAAAA:uuNCukj0I-HzgK9F441EsDB4rdcQGFys29pMFNqzS_OEeuKRqZ-mgEt5CP2Kibor0gI4WzqrwgEMGp-xAnXQuHotoWIDKnh6nYrUCcY37CJLMrjMzgI

Marks, S. B. (1997). Reducing Prejudice Against Children with Disabilities in Inclusive Settings. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 44(2), 117–131. doi: 10.1080/0156655970440204

Mastergeorge, A. M., & Martinez, J. F. (21n.d.). Rating Performance Assessments of Students With Disabilities: A Study of Reliability and Bias. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. doi: 10.1177/0734282909351022

Mentorship / Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://www.ccsoh.us/Mentorship.aspx.

Murawski, W. W. (2010). Collaborative Teaching in Elementary Schools: Making the Co-Teaching Marriage Work! Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Pindiprolu, S. S., Peterson, S. M., & Berglof, H. (2007). School Personnel’s Professional Development Needs and Skill Level with Functional Behavior Assessments in Ten Midwestern States in the United States: Analysis and Issues. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 8(1).

Preventing Suspensions and Expulsions in Early Childhood Settings A Program Leader’s Guide to Supporting All Children’s Success. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://preventexpulsion.org/1g-provide-professional-development-and-ongoing-support-for-all-program-staff-on-culturally-responsive-practices-and-implicit-bias/.

Skiba, R. J., Simmons, A. B., Ritter, S., Gibb, A. C., Rausch, M. K., Cuadrado, J., & Chung, C.-G. (2008). Achieving Equity in Special Education: History, Status, and Current Challenges – Russell J. Skiba, Ada B. Simmons, Shana Ritter, Ashley C. Gibb, M. Karega Rausch, Jason Cuadrado, Choong-Geun Chung, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/001440290807400301.

Special Education Terms and Definitions. (2019). Retrieved 20 November 2019, from https://www.understandingspecialeducation.com/special-education-terms.html

Zirkel, P. A. (2015). Special Education Law: Illustrative Basics and Nuances of Key IDEA Components – Perry A. Zirkel, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2019, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0888406415575377.

About IDEA. Https://sites.ed.gov/idea/about-idea/

Causton-Theoharis, J., & Theoharis, G. (2008). Creating inclusive schools for allstudents. School Administrator, 65(8), 24-25.

Chasson, G. S., Harris, G. E., & Neely, W. J. (2007). Cost comparison of early intensivebehavioral intervention and special education for children with autism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(3), 401-413.

Chang, Nicole. March 1, 2019. “Top 10 Campuses for Students with Physical Diabilities.” College Magazine.

Maheady, L., Harper, G. F., & Mallette, B. (2001). Peer-mediated instruction andinterventions and students with mild disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 22(1), 4-14.

Kutash, K., & Duchnowski, A. J. (2004). The mental health needs of youth with emotional and behavioral disabilities placed in special education programs in urban schools. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(2), 235-248.

Beyer, B., & Johnson, E. S. (2014). Special programs and services in schools: Creating options, meeting needs, revised. DEStech Publications, Inc.

IDEA. “Background of Special Education and the IDEA.” www.nea.org

Authors:

Ashley Hale

Zaynab Hashmi

Rachel Hempstead

Nichole Meredith