What would you say is the most prestigious category at the Oscars? I think it’s fair enough to guess that many – though perhaps not a majority – would say it is the Academy Award for Best Director. There seems to be a sort of allure to the director, to understand them as the key driving force behind a film. Thomas Schatz argues that we need to step back from that understanding of filmmaking (at least in the case of classical Hollywood). For Schatz it is not the director who is the driving force behind a film, but an ecological system wrangled (with varying degrees of success and actual control) by production executives.

A black and white image of the Hollywood sign

Schatz begins his argument by focusing on film criticism from the 60s and 70s. At this time, Schatz argues, the theory of film history was based on a “notion of directorial authorship” which highlighted “author-artists… whose personal style emerged from a certain antagonism to the studio system at large” (524). This action effectively elevated a sole few directors and movies, those which supposedly transcended the system of their creation and rendered invisible both parts of the career of these auteurs and a vast amount of film history. Such a view is quite myopic, Schatz claims, since the authority to produce auteurist films “came only with commercial success and was won by filmmakers who proved not just that they had talent but that they could work profitably within the system” (524). Considering this, Schatz argues we need to take a more ecological look at the system from which these movies emerged to determine who – if anyone – can be pointed to as the creative center of film in this era.

Ultimately, Schatz argues that more than any particular director, writer, actor, or individual movies from the Hollywood system were the result of:

a melding of institutional forces [where] the style of a writer, director, star, – or even a cinematographer, art director, or costume designer – fused with the studio’s production operations and management structure, its resources and talent pool, its narrative traditions and market strategy. And ultimately, any individual’s style was no more than an inflection on an established studio style. (525)

Schatz demonstrates this point – somewhat convincingly – by examining how several studios tended to treat the narrateme of a late night storm, from noirish (Warner Bros.), to glossy and upbeat (MGM), to the macabre (Universal). However, despite films from the Hollywood system but the ecology of each studio’s system and the technological, economic, and cultural matrices in which the studio and film goers lived, one particular role functions as a sort of lynch pin that keeps the whole ecology in balance and functioning.

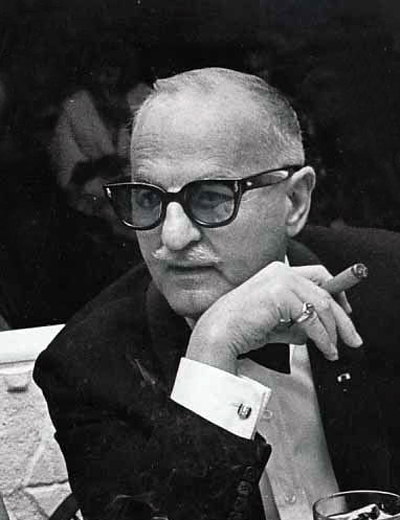

Darryl Zanuck, a production executive during the classical Hollywood period.

Production executives, Schatz claims, are this lynch pin. He writes:

these men – and they were always men – translated an annual budget… coordinated the operations of the entire planet, conducted contract negotiations, developed stories and scripts, screened ‘dailies’ as pictures were being shot, and supervised editing until a picture was ready for shipment to New York for release. (526)

For Schatz a film emerged from the studio ecology, but like a watering hole in the Savanna, production executives were the crucial element, both that which kept the ecology going and the place the ecology inevitably orbited. But Schatz is careful not to give too much authorial power to the production executive writing that, “isolating the producer or anyone else as artist or visionary gets us nowhere” (526). To punctuate this argument he quotes Bazin in saying “the American cinema is a classical art… so why not then admire in it what is most admirable – i.e, not only the talent of this or that filmmaker, but the genius of the system” (Bazin qtd. in Schatz 526). So, it is not the director, the actor, the writer, or producer who authors a film within the Hollywood system, though the producer has a particularly powerful function as the central nexus of filmic activity.

I wonder three things. First, did the Hollywood system truely die in the 1950s? Second, considering the power (cultural and economic) possessed by corporations like Disney, Netflix, and HBO are we seeing a reemergence of a studio system similar to the system of classical Hollywood? And, as a slightly far more reaching question, with the increasing ability of AI to produce startlingly coherent narratives are we moving into a place where authorship is very literally not the possession of any human agent?