First, let’s have a raise of hands. Who’s first comments were “what the hell did I just watch?” Only me? Alrighty, moving on.

What do “film poems” and “experimental” cinema have in common? Both terms fell out of use in the 50s and Sitney brought a new term into the cinematic scene: American avant-garde. The term avant-garde is one Sitney struggled with using as a ‘label’ for this thirty-year span of cinema.

Before I continue, I want to stop and ponder (diverge?) for a moment. This term avant-garde is often thrown around in reference to art, theater, cinema, etc. Sitney decided to use the term avant-garde because “it is the only name which is not associated with…the thirty-year span I [Sitney] attempt to cover” (preface, viii). A quick google search yields two definitions for the term avant-garde. The first definition: noun; new and unusual or experimental ideas, especially in the arts, or the people introducing them. The second definition: adjective; favoring or introducing experimental or unusual ideas. Both of these definitions include critical term. Experimental. So I want you to think, how do you define avant-garde? Is it some experimental conquest by an aspiring filmmaker? Is it a cry to be different? Towards the end of the preface, Sitney revisits the screening of avant-garde films in collegiate settings. “Hundreds of colleges now regularly screen avant-garde films; they have become an essential part of the program…Naturally the vast majority of independent films produced in any year are very low quality, as is the year’s poetry, painting, or music by and large” (preface, x).

On top of “film poems”, experimental, and avant-garde, Sitney brings in two more film types. The formal film and the structural film. The formal film can be described as a “tight nexus of content, a shape designed to explore the facets of the material.” Structural film however, exhibit four characteristics; the fixed (in the viewer’s perspective) camera position, the flicker effect, loop printing, and rephotography off the screen.

Although he is famously known for his pop art paintings, Andy Warhol also delved deep into the realm of avant-garde filmmaking. His early filmmaking harkens three of the four defining characteristics of structural film. These films included Sleep, a six-hour film which a half dozen shots have been loop printed ending with a frozen image of the sleeper’s head. The next films consist of Eat, a forty-five minutes of mushroom eating; eight continuous hours of the Empire State Building as seen in Empire; Harlot, a seventy-minute tableau vivant with off-screen commentary, and various others. As Olivia pointed out, Sitney writes that Warhol’s work opened up “a cinema actively engaged in generating metaphors for the viewing, or rather the perceiving, experience” (373).

Spring boarding off of Warhol’s avant-garde, “anti-romantic” structural films brings us to Brakhage’s

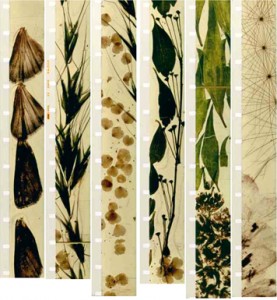

1963 film, Mothlight. When Mothlight was first mentioned in class a few weeks ago, I didn’t think much of. I understood to some extent that it’d be an ‘out of the box artsy type’ (avant-garde?) film but on the same note I never expect a FILM to be shot without a camera. Mothlight, to me, fits into this area of structural film. Fixed view perspective camera – check, flicker effect – check, loop printing and rephotography – can be argued. Brakhage collected hundreds of insect wings, petals, blades of grass, pollen, and leaves and meticulously pressed them together with tape and then fed that tape into a projector. This wasn’t just a short experimental film, this was his personal approach to his craft, his art.

“Here is a film that I made out of a deep grief. The grief is my business in a way, but the grief was helpful in squeezing the little film out of me, that I said “these crazy moths are flying into the candlelight, and burning themselves to death, and that’s what’s happening to me. I don’t have enough money to make these films, and … I’m not feeding my children properly, because of these damn films, you know. And I’m burning up here… What can I do?” I’m feeling the full horror of some kind of immolation, in a way. Over the lightbulbs there’s all these dead moth wings, and I … hate that. Such a sadness; there must surely be something to do with that. I tenderly picked them out and start pasting them onto a strip of film, to try to… give them life again, to animate them again, to try to put them into some sort of life through the motion picture machine.”[1]

Mothlight, a four-minute silent film, explores and blends aspects of “film poem”, experimental film, avant-garde, and structural films. The silence is filled with the soft crackling and popping of the tape. This crackling noise can be interpreted many ways by the audience. Is it the soft crackling of moth wings fluttering past? The popping open of flower petals as they bloom in the early morning light? The crackling and popping of a smoldering fire? Jacqueline Valencia, from These Girls On Film, summed Mothlight up in these two sentences, “[t]hese aren’t ghosts of things once real, these are flora’s antiquities roaming a projector’s lights. These things are real.” [2]

Mothlight, a four-minute silent film, explores and blends aspects of “film poem”, experimental film, avant-garde, and structural films. The silence is filled with the soft crackling and popping of the tape. This crackling noise can be interpreted many ways by the audience. Is it the soft crackling of moth wings fluttering past? The popping open of flower petals as they bloom in the early morning light? The crackling and popping of a smoldering fire? Jacqueline Valencia, from These Girls On Film, summed Mothlight up in these two sentences, “[t]hese aren’t ghosts of things once real, these are flora’s antiquities roaming a projector’s lights. These things are real.” [2]

“Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception.” – Stan Brakhage

“I make up the rules of a game and I play it. If I seem to be losing, I change the rules.” – Michael Snow

[1] Commentary by Stan Brakhage on By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume 1, taken from 2002 interview with Bruce Kawin retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mothlight

[2] Jacqueline’s full critique of Mothlight can be found here. I would highly recommend reading it if you are interested in seeing another opinion of the avant-garde scene and more specifically, Mothlight.