In 1966 the Vietnam War was underway with about 400,000 troops sent to fight in Vietnam. Tensions were high, many people disapproved of the war, and the government was keeping the events and massacres in Vietnam quiet. In November 1969 Nixon ordered a secret bombing of Cambodia and the incidences of the Mai Lai massacre were revealed. These details led to widespread disruption, unrest, and rioting. The areas under most of the anti-war demonstrations were college campus, and on May 4, 1970 4 students were shot dead at a Kent State University demonstration.

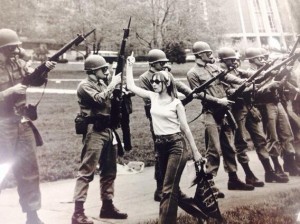

After the Kent State incident many college campuses feared a second “Kent State.” Students continued anti-war demonstrations; these demonstrations became increasingly violent and confrontational. Many personal accounts from the protesters state, “we (the students/protesters) ended the war,” but much of the administrative documents and faculty accounts present the demonstrations as disruptive, violent, and unhelpful.

The most common places on campus for performed demonstrations were on the Oval, on the edges of campus, and near the ROTC facility. Many protesters felt the need to voice their opinion not only on the war and the soldiers in combat, but also the ROTC students still on campus. Many of the ROTC students were called “baby killers” and other horrible names despite not even being involved in the war.

Demonstrations involved rock throwing, tear gas, confrontations between students and national guards, and many arrests. Once the demonstrations quickly turned violent and the Kent State shootings happened, Ohio State decided to close it’s campus for 2 weeks. From May 7- May 19 campus was closed off; students and faculty were not allowed anywhere on campus grounds. The closing seemed to work in the administrative favor because once Ohio State reopened the demonstrations were fewer and more peaceful. The demonstrations against the Vietnam War held a lasting effect on The Ohio State University; these lasting effects initiated by aggression and dissatisfaction towards the ROTC, where we leap into first.

We begin with the ROTC side of the dispute. According to the ROTC members and supporters, they are the victims of the protesters’ actions; and to the protestors, the ROTC are the aggressors and antagonizers. However, why were the ROTC viewed as the aggressors during the Spring of Dissent? Did the ROTC personally engage with the protesters before the demonstrations to fuel a fire large enough to consume the entire campus? No, the ROTC did not. The ROTC are a federal organization who were doing what the federal government ordered; that was to recruit soldiers for the Vietnam War.

The way in which the demonstrators voiced their opinions and dislikes of the ROTC program were considered closed fisted rhetoric, or more confrontational. They (protesters) resorted to the destruction of the ROTC grounds and the disruptive marching during several ROTC events. The response by the ROTC? Nothing. They went about their normal activities as if only a small hiccup occurred.

We see that the coercive/closed fisted tactics of the student demonstrators, compared to the cooperative/open handed response by the ROTC, were a total failure. Not only did the demands of the demonstrators not be met or heard due to their actions overpowering their rational voices, their members were arrested and charged with breaking several laws. For the ROTC, attendance rose to become the highest ROTC recruitment average in the nation.

The rhetoric we see implemented during this conflict gave thumbs up for one tactic and thumbs down for another. However, we cannot gauge rhetoric from one event because as we all know, each social movement is a unique organism that functions specifically to sustain life and meaning for itself. As in the Spring of Dissent, it seems that the symbiotic tendencies of the ROTC outlived the parasitical tendencies of the demonstrators. Now that the ROTC side of the conflict has been examined, it’s time now to shift our focus to the opposing side of the Spring of Dissent: the demonstrators.

The anti-war movement at The Ohio State University during the Spring of Dissent was a defining factor of progress at the University. The use of melodramatic rhetoric morally polarized people, forcing them to have difficult conversations that challenged personal opinions about the war. The use of open fisted rhetoric by the anti-war movement demonstrate the students’ passion to get their voice heard. These students were not interested in putting down the opinions of others, but rather, challenged others to see the facets of the war that were present at The Ohio State University, like war research and the ROTC program. Out of frustration, the movement took more of a closed-fist approach. Other political factors, like the United States invasion of Cambodia, as well as the Kent State University shootings served as catalysts for the abrupt change in rhetorical style. Student and faculty participating in the anti-war movement challenged their peers to look at the Vietnam War through a different lens by bringing to light the war research that was happening at OSU. Some felt that the war research at OSU was fine. On the other hand, some felt that the war research was hindering student’s education. Other students were uncomfortable getting an education from a University so involved in a war that they did not particularly agree with. Instead of accepting government official’s decisions entirely, the anti-war movement questioned the decisions of authority, consequently sparking intelligent conversation amongst faculty and students. These types of conversation helped people compartmentalize the chaos around them.

The anti-war movement is unique because of all of the conversations it started. As a result of the chaos during the Spring of Dissent, teachers held classes in their homes and had open dialogue about the war. Had these discussions not taken place, the course of our University’s history would have been changed. For starters, the sense of unity, as a result of the movement, would have not been present. Students would not feel unity because they would not have felt they had a role in ending the war. Finally, had this movement not happened, some students would not even be aware of the role OSU administration had in the war. The anti-war movement is an irreplaceable part of The Ohio State University’s history because of the progress in unity and awareness the University made in a time of overwhelming chaos.

In conclusion, the late 1960’s and early 1970’s were characterized by a highly active, engaged body of students who protested various injustices, or perceived injustices, of the time. It was a time of great unrest — pacifists protested the Vietnam war, people of all ethnicity fought racial inequality, and women spoke out against their oppression. Such injustices, in various forms, persist even today, so we must consider the motivations and environment that contributed to the conglomeration of social movements that intertwined into the Spring of Dissent. To examine the causes, we will discuss the overall theme of injustice that pervaded the time period and the infectious nature of social movements.

Protests, sit-ins, marches: they all linked back to the idea of injustice. It was unjust that American men were overseas, “killing babies” for a cause that an overwhelming majority of Americans did not believe in. It was unjust that women received unequal pay and were less liberated men. It was unjust that black Americans were forced to use separate, often inferior facilities than white Americans as a result of segregation. Finally, in the late 1960’s, these injustices came to a head. Many Americans opposed the draft, and rejected the notion of fighting for a cause that inherently violated their values. However, this rang especially true for young black men, who were subject to die the same death as young white men to fight for rights that they themselves were not granted. Although the following clip may not be 100% historically accurate and is likely dramatized for cinematic effect, it depicts the fusion of two movements into what some would consider one larger movement against inequality as a whole.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KnpnYAId6dU

These movements built off one another for more than just similar goals. College campuses are hubs for bonding capital, or significant connections made between individuals on a basis of close interaction. Social capital, in turn, leads to increased civic engagement (Zukin et. al). Additionally, it allows for the transfer of ideas during normal discourse, and provides easy opportunity for students to engage in passionate conversations about such heavy topics as these injustices. Finally, those who are involved in social networks spawned by bonding capital face the chance of being left out if they don’t attach to the norms, essentially a more mature form of peer pressure. As Anthony Libby, then English Professor put it:

Although most students participating in the protest were politically motivated, there was an element of ‘play’ to the rallies. Some young people were just excited to be a part of the huge crowds of people that gathered around campus. (Lantern Archives)

The swelling sentiment against gross injustices combined with the intellectually and culturally stimulating environment of college campuses in the 1960’s and 1970’s resulted in the Spring of Dissent. College students across the nation used the platforms created by the frenzied atmosphere in efforts to affect change, and many believe they truly did.

*For people who witnessed the events of the Spring of Dissent, if you would like to share your experiences, you can follow this link and answer a few questions regarding the demonstrations and how you perceived them: https://spreadsheets.google.com/viewform?formkey=dFVCZVJ5eS1WMjNpWU5MeUxBRklVQ3c6MQ

Zukin, Cliff, Scott Keeter, Molly W. Andolina, Krista Jenkins, and Michael X. Delli Carpini. A New Engagement? : Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. I ed. Vol.