CEO: Demonstrate a commitment to ethical principles pertaining to provision or withholding of care, confidentiality, informed consent, and business practices, including compliance with relevant laws, policies, and regulations

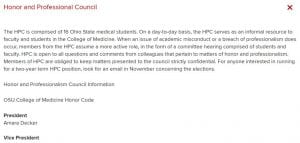

The meaning of professionalism has changed for me throughout my medical school career. During my first two years I was involved with the Honor and Professionalism Council, first as a class representative and then as president of the council. My desire to serve on the council stemmed from an understanding that as a profession, medicine requires physicians to demonstrate a level of professional knowledge and professional behavior. This is because professionalism is one of the basic tenets of the field of medicine. The OSUCOM Professionalism and Core Educational Objectives outline some of the key aspects of professionalism and requires students to demonstrate “compassion, respect, honesty, accountability, altruism, prudence, social justice, and commitment to excellence in all professional and personal responsibilities”. My goal with HPC was to ensure that all students had the opportunity to demonstrate those competencies but also to learn how to improve in areas where they may not be as strong. Given the diversity of backgrounds of OSUCOM students, we all entered medical school with varying understanding of respect, social justice and even accountability. However, the aim is that by the end we are all at the same level— and at our highest level possible. For me as I enter residency I hope to keep this same frame of mind and continue to treat my patients and colleagues with compassion, respect, honesty and prudence; and that in my work I will demonstrate accountability, altruism, social justice and a commitment to excellence.

As I reflected on this CEO I thought about my clinical rotations and the various examples of professionalism and unprofessionalism that I witnessed. In each encounter I attempted to reflect on what I could emulate and what I would do a little differently. One example was during my family medicine ambulatory rotation. The attending I was working with on that day was about 30-minutes behind on each patient. As we got to the next patient he was irate. He felt that the attending did not respect his time because we were delayed. The moment that we walked into the room the patient was glaring at us stating “you can’t be serious. Do you know the time?” Before the attending could even offer his apologies or an explanation the exasperated patient was raising his. While the patient was angry the attending maintained his cool and remained professional allowing the patient to continue speaking. From this I learned that professionalism is exemplified by our actions and also out reactions to situations outside of our control. The attending handled the situation by first diffusing the patient’s anger, and then secondly allowing the patient to feel heard. This left a great impression on me and caused me to feel that if ever in that situation I would know how to behave. I also felt that I learned about the patient and what things were important to him. I learned from that encounter the importance of timeliness to patients, but also the value of clear communication. By allowing the patient to speak and then clarifying the reason for the delay it was easier for the patient to understand an unplanned delay. This encounter was beneficial to me especially during my EM rotation when I often had to deal with hostile or inebriated patients while maintaining my professionalism. I tried to reflect on this encounter and utilize the same skills I saw the physician use: listen, apologize then chart a plan forward.

As I go toward residency my goal is to demonstrate professionalism and ethical behavior in my interactions with classmates, patients and faculty. Additionally, I hope to be a leader in helping to foster a culture of professionalism at OSU. One way that I have tried to leave that legacy was with working on the Class of 2020 Oath Committee. As part of the oath that every graduate will saying during the hooding ceremony is language which focuses on maintaining integrity, honesty and professionalism.

Image of the draft of the 2020 Class Oath: