-

Incorporating frequent quizzes into a class’s structure may promote student learning. These quizzes can consist of short-answer or multiple-choice questions and can be administered online or face-to-face. … Providing students the opportunity for retrieval practice—and, ideally, providing feedback for the responses—will increase learning of targeted as well as related material.

-

Providing “summary points” during a class encourages students to recall and articulate key elements of the class. Setting aside the last few minutes of a class to ask students to recall, articulate, and organize their memory of the content of the day’s class may provide significant benefits to their later memory of these topics. Whether this exercise is called a minute paper or the PUREMEM (pure memory, or practicing unassisted retrieval to enhance memory for essential material) approach, it may benefit student learning.

-

… Pretesting students’ knowledge of a subject may prime them for learning. By pretesting students before a unit or even a day of instruction, an instructor may help alert students both to the types of questions that they need to be able to answer and the key concepts and facts they need to be alert to during study and instruction.

-

Finally, instructors may be able to aid their students’ metacognitive abilities by sharing a synopsis of these observations. … Adding the potential benefits of pretesting may further empower students to take control of their own learning, such as by using example exams as primers for their learning rather than simply as pre-exam checks on their knowledge.

Author: Melinda Rhodes-DiSalvo

Learning Activity Focuses on Future General Practice Application of Technology

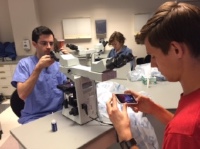

This semester, Drs. Jessica Hokamp and Maxey Wellman have introduced an activity into their cytology elective course that both anticipates increased future application of technology in general practice and supports student ability to identify the ideal area on a lymphoma slide for diagnosis.

Some practitioners are sending cell phone images to pathologists for diagnosis, and their activity asks students to effectively use the microscope, identify areas and cells being viewed, and capture the area identified using the iPhone.

Pictured are students attempting the capture. Drs. Hokamp and Wellman plan to refine the pilot learning module into a teaching and learning research project.

Free Online Course Teaches You to Learn How to Learn

And it’s free. The following tips from the course instructor are included in the NYT article:

FOCUS/DON’T

The brain has two modes of thinking that Dr. Oakley simplifies as ‘focused,’ in which learners concentrate on the material, and ‘diffuse,’ a neural resting state in which consolidation occurs — that is, the new information can settle into the brain. (Cognitive scientists talk about task-positive networks and default-mode networks, respectively, in describing the two states.) In diffuse mode, connections between bits of information, and unexpected insights, can occur. That’s why it’s helpful to take a brief break after a burst of focused work.

TAKE A BREAK

To accomplish those periods of focused and diffuse-mode thinking, Dr. Oakley recommends what is known as the Pomodoro Technique, developed by one Francesco Cirillo. Set a kitchen timer for a 25-minute stretch of focused work, followed by a brief reward, which includes a break for diffuse reflection. (‘Pomodoro’ is Italian for tomato — some timers look like tomatoes.) The reward — listening to a song, taking a walk, anything to enter a relaxed state — takes your mind off the task at hand. Precisely because you’re not thinking about the task, the brain can subconsciously consolidate the new knowledge. Dr. Oakley compares this process to ‘a librarian filing books away on shelves for later retrieval.’ … ‘Virtually anyone can focus for 25 minutes, and the more you practice, the easier it gets.’

PRACTICE

‘Chunking’ is the process of creating a neural pattern that can be reactivated when needed. It might be an equation or a phrase in French or a guitar chord. Research shows that having a mental library of well-practiced neural chunks is necessary for developing expertise.

‘Practice brings procedural fluency,’ says Dr. Oakley, who compares the process to backing up a car. ‘When you first are learning to back up, your working memory is overwhelmed with input.’ In time, you don’t even need to think more than ‘Hey, back up,’ and the mind is free to think about other things.

‘Chunks build on chunks, and,’ she says, the neural network built upon that knowledge grows bigger. ‘You remember longer bits of music, for example, or more complex phrases in French.’ Mastering low-level math concepts allows tackling more complex mental acrobatics. ‘You can easily bring them to mind even while your active focus is grappling with newer, more difficult information.’

KNOW THYSELF

Dr. Oakley urges her students to understand that people learn in different ways. Those who have ‘racecar brains’ snap up information; those with ‘hiker brains’ take longer to assimilate information but, like a hiker, perceive more details along the way. Recognizing the advantages and disadvantages, she says, is the first step in learning how to approach unfamiliar material.

Tips For Giving Feedback in the Clinical Environment

- Establish a respectful learning environment.

- Communicate goals and objectives for feedback.

- Base feedback on direct observation.

- Make feedback timely and a regular occurrence.

- Begin the session with the learner’s self-assessment.

- Reinforce and correct observed behaviours.

- Use specific, neutral language to focus on performance.

- Confirm the learner’s understanding and facilitate acceptance.

- Conclude with an action plan.

- Reflect on your feedback skills.

- Create staff-development opportunities.

- Make feedback part of institutional culture.

Quick Tip for Multiple Choice Questions

- If two answers are opposite, one is probably correct.

- Answers with the following words are usually incorrect: always, never, all, must

- Answers with the following words are usually correct: seldom, generally, tend to,

- probably, usually

- Look for grammatical clues between the question and the choices. For example, the question and the correct answer often have verbs of the same tense and have nouns and verbs that agree.

- Underline familiar words or phrases from the lecture or textbook.

- Be aware of degrees of correctness. With numbers one choice is usually too small or too large. These choices may be eliminated.

Various uses of the term, “Assessment”

Q: I keep on hearing about assessment. Assessment as in a test, assessment as in learning outcomes, assessment as in course assessment, assessment as in program assessment. What’s up?

A: The term, “assessment,” when commonly used at the college refers to a midterm or final exam, or another assignment designed to test for student acquisition of foundational knowledge or ability to clinically reason. In this sense, “assessment” serves as another word for examination.

Assessment can also refer to a plan or structure established for constant course and program improvement, and a way to ensure a college is collectively doing what it says it does — that students learn what we say they will during their time with us.

Because examinations are designed to test student knowledge, it would seem reasonable to equate the exam with learning outcomes achievement. This assumes that questions on examinations are aligned (directly related to) stated outcomes for a lecture or course or program.

“There is often confusion over the difference between grades and learning assessment, with some believing that they are totally unrelated and others thinking they are one and the same. The truth is, it depends. Grades are often based on more than learning outcomes. Instructors’ grading criteria often include behaviors or activities that are not measures of learning outcomes, such as attendance, participation, improvement, or effort. Although these may be correlated with learning outcomes, and can be valued aspects of the course, typically they are not measures of learning outcomes themselves.

“However, assessment of learning can and should rely on or relate to grades, and so far as they do, grades can be a major source of data for assessment.” (http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/howto/basics/grading-assessment.html#scoringparticipation)

When deciding on what kind of assessment activities to use, it is helpful to keep in mind the following questions:

- What will the student’s work on the activity (multiple choice answers, essays, project, presentation, etc.) say about their level of competence on the targeted learning objectives?

- How will the instructor’s assessment of their work help guide students’ practice and improve the quality of their work?

- How will the assessment outcomes for the class guide teaching practice?

Learning Journals Promote Reflective Learning

Why use a learning journal?

- To provide a ‘live picture’ of your growing understanding of a subject or experience.

- To demonstrate how your learning is developing.

- To keep a record of your thoughts and ideas throughout your experiences of learning.

- To help you identify your strengths, weaknesses and preferences in learning.

Check out this handoutLearning_Journals-qx3u17 on learning journals for more information.

How’s Your Notetaking

- Avoid transcribing notes (writing every word the instructor says) in favor of writing notes in your own words.

- Review your notes the same day you created them and then on a regular basis, rather than cramming review into one long study session immediately prior to an exam.

- Test yourself on the content of your notes either by using flashcards or using methodology from Cornell Notes. Testing yourself helps you identify what you do not yet know from your notes, and successful recall of tested information improves your ability to recall that information later (you will be less likely to forget it).

- Carefully consider whether to take notes on pen and paper (or iPad and pencil) or with a laptop. There are costs and benefits to either option.

- We are often misled to believe that we know lecture content better than we actually do, which can lead to poor study decisions. Avoid this misperception at all costs!

Conversation Focuses on Answering Tough Questions about Grading and Feedback

During a Wednesday, Sept. 6, presentation, Dr. Julie Byron, and Melinda Rhodes-DiSalvo, Ph.D., as well as a group of faculty, sat down to wrestle with “Answers to Tough Questions about Grading and Student Feedback.” A few highlights follow.

Gameful Course Design Supports Intrinsic Motivation

If students approach learning the same way they do video games, imagine the benefits, suggested Rachel Niemer , director of the Gameful Learning Lab at the University of Michigan. GAMEFUL PEDAGOGY and gameful course design, she added, encourage learners through support of intrinsic motivation.

, director of the Gameful Learning Lab at the University of Michigan. GAMEFUL PEDAGOGY and gameful course design, she added, encourage learners through support of intrinsic motivation.

Neimer spoke at OSU’s Innovate Conference held May 16.

“When gamers come (into a gaming session), they start at 0 and build learning credit for how they learn, as well as competency,” she explained. The reverse is true in the typical classroom where students start at 100 and then are penalized for errors.

Moreover, in classrooms, students often complain about content being too difficult or too complex. To the contrary, if a game is too easy, people stop playing. “Ideally, students would be intrinsically motivated to do the difficult job of learning,” she said. “… In games, people are intrinsically motivated.” There’s also a sense of play involved, which is rewarding in and of itself.

According to Niemer, gamification encompasses theories of motivation and the learning sciences. Three components of motivation, for example, are autonomy, belongingness, and competency. Application of game principles to non-gaming activities, as a result, can be powerful.

Some methods for adding gamefulness to a course include:

- Framing the course as a competition not for grades, but for indications of competency like badges that accumulate on a student’s profile page or in an application.

- Providing students with choices on how to play or earn a grade.

- Offering students the ability to design their own assessments of learning.

- Creating a method whereby students can see their own progress (not measured in grades but in tasks completed but not deadlined, for example) and compare it to other students’ progress in a course.

Allowing students the opportunity to “predict” points they will earn on activities and assess where to put their time and energy. (They already do this, Niemer said, trading off performance on one class’s assignments to study for an exam.)

Niemer and her colleagues have created a gradebook tool called GradeCraft that manages gameful courses and supports gameful course design. Instructors can purchase individual copies if their first experiments with gameful pedagogy show promise.

“Impact Student Motivation: Make School a Better Game” is available for viewing in its entirety.