It could be argued that the entire book is about identity, power, and injustice – these ideas recur throughout and change as Coates refines his thoughts over time. Much of the opening section talks about Coates’s childhood, which he compares to the white childhoods he saw depicted on TV; while he was constantly alert, learning the language of the streets and having a gun pulled on him in sixth grade by another boy, “[t]here were little white boys with complete collections of football cards, and their only want was a popular girlfriend and their only worry was poison oak” (20). This seemed worlds away from him, and despite not fully understanding at the time, felt like “a cosmic injustice, a profound cruelty” (21). It’s clear that he often felt a sense of injustice, even in moments where it doesn’t seem like anything really “happened.” This disparity between white and black life in the US could definitely be examined as a One/Other relationship, even though Coates’s experiences are entirely separate from white people until his college years.

Later, Coates talks about finding his identity through his experience as a student at Howard, a historically black university. This was when he was first able to meet black people with different backgrounds than him, which taught him all kinds of new things about himself and black people as a group. He states: “The black world was expanding before me, and I could see now that that world was more than a photonegative of that of the people who believe that they are white” (42). Now, he no longer defines himself as opposite from what he knew about whiteness, and begins to solidify his identity as a black man through reading works about African history and by black authors.

The idea of power comes up in many ways, but the most common (and poignant) is through Coates’s experience with one of his Howard friends being killed by a police officer. The officer who killed him followed him across state lines under the pretense of looking for a suspect who looked completely different, shot him several times with shoddy reasoning, faced no consequences and returned to his work (80). This led Coates to investigate the institutions that allowed this to happen, and the ways that they are predisposed against black people and have been from the start. This supports the idea that he emphasizes throughout the book: that destroying the black body is a given and beneficial act for the US, and has always been throughout its history. This is the big idea of what Coates wants the average reader to take away. That said, the book masterfully weaves together themes of identity, power, and injustice in a way that allows almost any element of it to inspire its own conversation.

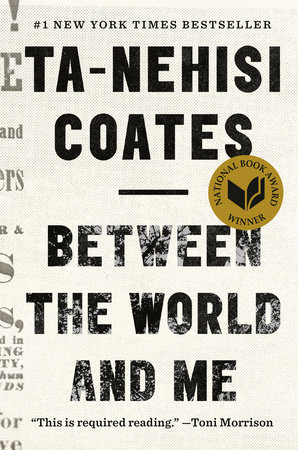

Coates and his son