Overview

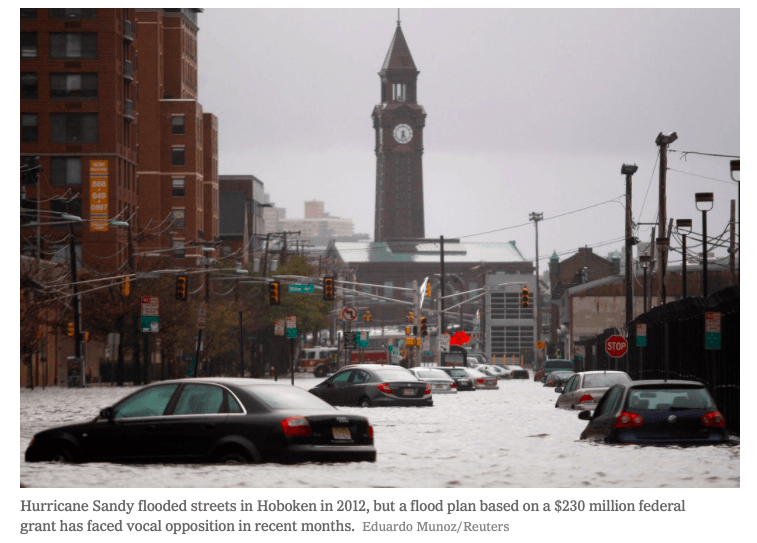

Hurricane Sandy was named during the hurricane season of 2012. It started to form in the central Caribbean and made its way up the East Coast, eventually reaching landfall in New Jersey. (Picture #1) It had winds that reached 80 mph. The storm flooded streets and caused immense damage destroying homes, businesses, power lines and landmarks around the city. (Picture #2) The storm continued east leaving 15 states without electricity. Many people were killed or severely hurt from the strength of the storm.

Communication

At first, the articles described more material impacts, such as those affecting power and transportation systems. The loss of electricity was a major focus of many of the articles with variations of additional focus on other issues like housing, hospital issues, and fires. Immediately following the hurricane, these problems were quickly mentioned without a large amount supporting information. As time passed after the hurricane, articles became longer and featured more in-depth information, with a shift in focus from material loss to human loss. The articles that were written later also focus on the much larger consequences such as economic impact and mental health problems. The progression of material covered went from quick information (immediately after the hurricane) to more in-depth analysis and description about all of the damages (longer span of time since the hurricane). Stories about people’s situations also began to make an appearance in the later articles more than those in the first few days after the storm. The tone definitely changes over time as it seems at first more urgent about the damages, and over time, reporting is less frequent and less pressing about the hurricane. Accuracy also improved, as estimates of damage became more accurate as time passed. Overall, human and material impacts were covered in all the articles, with early articles focusing on immediate concerns and latter articles focusing on larger scale issues.

Names and Dates of Articles Used for CommunicationSection

- Sandy’s Aftermath: 33 dead, millions without power (10/30/2012)

- Hurricane Sandy: The Aftermath (11/01/2012)

- Hurricane Sandy: High Winds and Flooding Hit US East Coast (10/29/2012)

- Hurricane Sandy: October 29 as it happened (10/29/2012)

- Sandy’s Impact: State by State (10/31/2012)

- In New York City, a rising death toll from Sandy (11/01/2012)

- Superstorm Sandy: Facts About the Frankenstorm (11/27/2012)

- The Night Hurricane Sandy Hit New York City (10/29/2013)

- Hurricane Sandy’s Impact (10/29/2013)

- Hurricane Sandy, five years later: ‘No one was ready for what happened after’ (10/27/2017)

- Hurricane Sandy Facts, Damage and Economic Impact (09/22/2018)

- Superstorm Sandy Struck 6 years Ago Today; What’s Changed? (10/29/2018)

Vulnerability

There were a variety of factors, some man-made and some natural, that contributed to the intense degree of devastation seen along the East Coast following the hurricane. One of the biggest causes for such large-scale devastation was the location of the cities themselves. Areas such as Hoboken, New Jersey and Lower Manhattan lie at or below sea-level, meaning that the areas are “notoriously susceptible to flooding even after just a heavy downpour.” (McGeehan n.pag) (Picture #3) These communities lacked both the hard engineering solutions (levees, surge barriers, etc.) and the natural barriers (living shorelines, wetlands) needed to weaken the strength of the storm. The lack of such infrastructure meant that these low-lying areas were hit by the storm at full force, resulting in over $72.1 billion in damages. (Miller 2) Another problem that contributed specifically to New York’s material devastation was the flooding of the subway system by large amounts of saltwater. “Salt can eat at the motors, metal fasteners, and electronic parts, some many decades old, that keep the system running.” (Mann n.pag) Hurricane Sandy managed to flood all 10 of the subway tunnels located in lower Manhattan, resulting in widespread damage to subway infrastructure – some of which has been in service for over 100 years. (Picture #4) The age of such equipment proved to be a source of vulnerability, because when flooded equipment refused to restore function, engineers could not simply order parts to repair them, as they were no longer available. (Mann n.pag) Such weaknesses in New York City’s transportation network had massive consequences, as the 4.3 million people that depend on the subway every day were rendered immobile for over a week, hurting the area’s economy.

Future Improvements

Major coastal communities must strive to improve engineering on a number of fronts in order to avoid both surface-level and underground infrastructure damage. One way in which cities can mitigate underground flooding damage is by developing and implementing grating and entry flood-prevention techniques. Sealable aluminum covers for street grating and inflatable, sealable barricades for subway entrances can help mitigate underground flooding and infrastructural damage. Cities can alleviate ground-level damage by constructing coastal defenses such as levees, sea walls, and natural wetlands. (Miller n.pag) (Picture #5) Another key aspect to reducing an area’s vulnerability to natural disaster is the implantation of evacuation warnings/procedures. A major issue in Hurricane Sandy was a delayed evacuation command and many people ignoring the evacuation. Taking evacuations seriously and responding accordingly is an important measure in short-term and long-term safety. Most importantly, individuals need to develop emergency response protocols and emergency kits. Although located directly on the coast, near or at sea level, many people failed to have emergency planning before Hurricane Sandy. Evacuation and contingency planning and emergency kits can expedite responses during emergencies, backup plans in case of failure, and mitigate some of the stress and panic of emergency situations.

Implementation

There are a number of significant barriers that prevent East coast communities from implementing new strategies to prevent future hurricane/storm damage. The largest of these barriers comes from an unexpected source; the citizens that would benefit from such improvements. Such opposition is seen in places like Hoboken, where NIMBY-like movements occur as residents protest the construction of a sea wall that would prevent flooding in the city but also ruin the beautiful view of Manhattan. (McGeehan n.pag) Even when projects are supported by residents, other barriers persist. One such hindrance is the magnitude/complexity of the projects needed to “flood-proof” the coastline, many of which are the first of their kind. (Picture #6) The implementation and construction of these improvements takes large amounts of time and money, leaving communities vulnerable until construction has been completed. (Jorgensen n.pag) In order to minimize these barriers, communities must attain commitment from citizens and long-term funding to support major projects through their completion. Without such improvements, the East coast will continue to be susceptible to hurricanes and thus significant economic damage.

Sources

- livescience.com/24380-hurricane-sandy-status-data.html

- http://nf4hr2ve4v.search.serialssolutions.com/?rft.title=Wall+Street+Journal+%28Online%29&sid=sersol%3ARefinerQuery&SS_issnh=2574-9579&issn=2574-9579&url_ver=Z39.88-2004&l=NF4HR2VE4V&SS_LibHash=NF4HR2VE4V&SS_ReferentFormat=JournalFormat&rft.genre=article&rft.issn=2574-9579&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.atitle=Salt+Water+Puts+Subway+%27in+Jeopardy%27

- https://fordham.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=environ_theses

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/08/nyregion/plan-to-flood-proof-hoboken-runs-into-a-wall.html

- http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-vulnerable-storms-5-years-hurricane-sandy-article-1.3597208(Solutions)

- https://web.tplgis.org/NYC_CSC/pdfs/Eval%20of%20NYC%20Coastal%20Vulnerability%20TPL%203-3-2016.pdf

- http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/nyc-vulnerable-storms-5-years-hurricane-sandy-article-1.3597208