This week, we are reading Susan Sontag’s, “Regarding the Pain of Others”. In this piece, she discusses war photography, so I would live to give some background and context on the subject. In general, photographs taken during war capture the scenes around them, taking note of the environment, the people, and can tell more about the emotion of war than text can. Everyone has heard the phrase “a picture speaks a thousand words”, and this holds true when looking at photos taken during war. War photography images are gut-wrenching, and they paint the picture of war for those who did not experience it.

While there have been such a large amount of soldiers fighting in wars for hundreds of years, there are even more people who have not, and will not, experience it firsthand. That is where the role of war photographers becomes so vital. They control what gets seen, and how people who are not on the frontlines view the war (PictureCorrect). There are so many emotions that war brings out of people, and war photography depicts these emotions. So what is war photography? War photography is any visual representation of the images of, or related to war, especially in photographs. Though pictures by camera is what most people think of, before the invention of the camera, war scenes were painted by hand (PictureConnect). Though the first known photographs of war were taken in the year 1847 (Artstor), painting war scenes dates back even further. These images showed the highest highs and lowest lows of war; it showed the heroic wins and the pain and suffering.

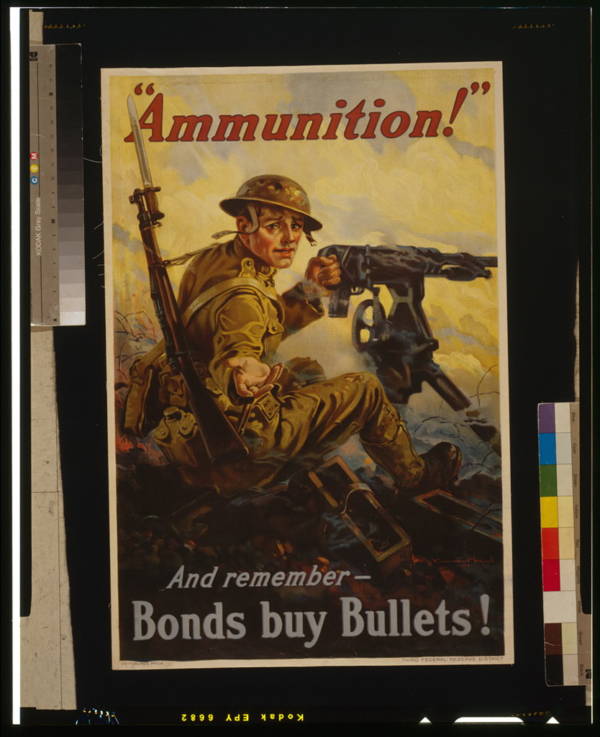

In addition to these images bringing the harsh realities of war to people who did not see it for themselves, war photography became a mode of propaganda. Images were used to shape opinions of individuals who saw them. Many images were made into some sort of cartoon, or was put with a catch-phrase in order to grab attention and sway people’s thoughts on war. Sometimes these messages would be legitimate and correct, but sometimes they would have false information (British Library). Propaganda has also been known to be used to boost morale and patriotism in hard times, and recruit more soldiers to fight.

War photography plays a huge role in the war itself, especially by being a window into the action to the people not physically fighting. Whether it be paintings, propaganda, photos, or other visuals, people could further understand what being in the action of war is like.

Sources:

https://www.artstor.org/2016/11/11/seeing-is-believing-early-war-photography/

https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/propaganda-as-a-weapon

Pics:

https://allthatsinteresting.com/world-war-1-propaganda-posters

https://www.popphoto.com/news/2011/06/terror-being-war-photographer/

Hi Carly,

I found this context research presentation to be extremely powerful. One of my best friends is studying photojournalism, so I had heard the importance of that course of study from him and it was interesting to hear about it from a different lens. I agree with you that war photography is absolutely gut-wrenching; ever since the Civil War, when the camera was popularized enough to actually capture war scenes, we have been able to understand the magnitude of these instances and reflect accordingly. I agree, too, that they can be utilized as a form of propaganda. All in all, fascinating work, and I found this useful as we move forward in this course.

Interesting to read, especially in the context of how powerful visual media can be in shaping narratives. War photography, as described, offers a raw and emotional idea of experiences that many will never face firsthand. I’m currently working on an an autobiographical experience 500 words paper, where I explore personal moments that have shaped my perspective. Like war photography, autobiographies provide an intimate lens into someone’s life, bridging the gap between individual experiences and broader understanding.