A new study from a Fisher College of Business professor suggests research and development teams could use some more outside-the-box thinking in how they structure and manage their own innovation projects.

The research appeared in Production and Operations Management journal titled: “The Role of Project and Organization Context in Managing High-Tech R& D Projects.” This study employs both qualitative case data and survey data from more than 100 R&D projects at nearly 34 high-tech organizations is authored by Aravind Chandrasekaran, an associate professor of management sciences at Fisher.

In his research, Chandrasekaran found that companies are making a very common mistake in managing their R&D projects, and the consequences can range from an internal preference towards cut-and-dry, quick-turnaround innovation projects to loss of market share and competitive edge.

Context is key

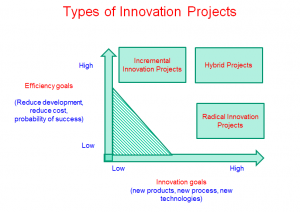

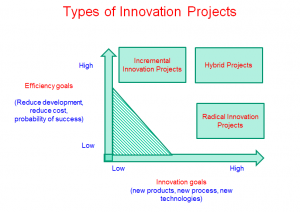

At the root of this increasingly troubling trend among R&D teams is a common villain: The tried-and-true approach, backed by decades of research and results. Projects typically are categorized and managed by the extent of change in the product, process, technology and market dimensions. A routine iPhone upgrade from a 3G to a 3GS, for example, falls at one end of a continuum as a so-called incremental innovation project.

“If you’re going from a CD player to an iPhone, though, that’s radical innovation,” Prof. Chandrasekaran said.

This research posits that R&D project management shouldn’t be determined on a sliding scale of eventual change, big or small. Rather, it should be driven by project goals, whether they’re to explore a new technology or to exploit opportunities for efficiencies, cost savings or faster time to market, Prof. Chandrasekaran said.

The research found that incremental and radical innovation projects thrive under two entirely different sets of so-called project and organizational contexts. Incremental projects need diligent, transactional leaders at the helm, low levels of team-member autonomy and well-defined goals that are tied to outcome-driven incentives. Radical innovation projects, meanwhile, need a leader who’s willing to promote risk-taking and experimentation, give team members more latitude and reward them at milestones, not just the finish line.

Crossing these wires, the research found, can be deadly for project success. Put a rigid, transactional leader in front of a radical project team and the creative juices stop flowing. Give incremental project teams more autonomy and a hands-off approach and deadlines are missed.

A one-size-fits-all approach to project tracking, all too common in the companies surveyed, spells trouble, too. Teams juggling a mixed bag of projects, all with the same metrics and reporting structure will develop a Pavlovian affinity for the fast and predictable incremental ones and leave the long-term radical ones on the to-do list.

Double-dipping

Here’s the nuance that even the savviest high-tech companies miss in their ongoing R&D project management efforts: Some projects in these environments are driven by goals typically associated with radical innovation and incremental innovation, but existing research doesn’t offer much help on how to deal with them, Prof. Chandrasekaran’s research found.

These so-called “hybrid projects” aren’t new to post-recession R&D departments, but they’re making more appearances as companies are asked to do more with less or – at best – the same.

“In this day and age, budget cuts are more and more visible in R&D environments, and companies are being asked to make big leaps in projects, pushing up deadlines without giving additional resources,” he said.

The growing stakes of maintaining competitive edge are outpacing overall R&D spending, too. An annual Battelle report on R&D expenditures found U.S. spending is set to grow about 2.5 percent this year, on par with the growth in the national Gross Domestic Product but slower than the global growth rate of 3.4 percent.

The key to nurturing these hybrid projects, Prof. Chandrasekaran found, is first not to let them get incorrectly classified as radical innovation projects, the most frequent mistake. Key red flags to look out for include the addition of deadline or cost pressure to an otherwise radical innovation project.

“In practice, organizations are pretty good at making changes between radical and incremental projects,” he said. “They often fail to make that change for hybrid projects.”

What these projects need, according to the study, is a so-called “ambidextrous leader” who knows when to shift between hands-off management during bursts of team creativity to taking the reins and steering the project on time and on budget. For instance, an ambidextrous project leader from one of hybrid project remarked the following:

“And the expectations are certainly higher to meet our project timelines, since these timelines rarely gets expanded by the senior management. So my role is to drive my team members to meet these deadlines [transactional]….. However, there were occasions when we encountered a lot of unknowns wherein I need to step back and allow my team to tackle these unknowns. Definitely, I am more tolerant and flexible during these times [transformational].”

Not just for tech

Tapping into high-tech companies for this study, Prof. Chandrasekaran said, wasn’t an act of random selection. The tech sector remains the R&D industry’s most fertile ground for growth, but that doesn’t mean this research is valuable only to them.

Any company investing in R&D should take notice of the opportunities they’re missing as they organize and deploy project teams, he said.

“This research shows management has to make key changes,” Prof. Chandrasekaran said, with the following questions: “How do you reward these people? How do you lead these teams? When do you give them decision – making autonomy? When do you take back the same decision-making autonomy?”

In short, effective senior management support in R&D doesn’t stop after signing off on a budget. That’s just the beginning.

- Chandrasekaran, A., Linderman, K., Schroeder, R.G.2015. The Role of Project and Organizational Context in Managing High-Tech R&D Projects. Production and Operations Management 24(4) 560-586.