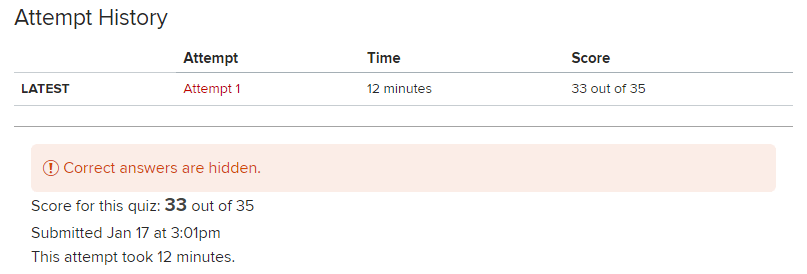

Interprofessional Collaboration

7.2 Use the knowledge of one’s own role and the roles of other health professionals to appropriately assess and address the healthcare needs of the patients and populations served

As a pharmacist who is now in medical school pursuing a career in medicine, I have long thought there is value in an interprofessional team to take care of patients, especially complicated ones with multiple comorbidities or rare diseases. I got to see the value of this type of team during my rotation in pediatric cardiology at Nationwide Hospital. During my time on this rotation I was exposed to some extremely rare cardiac abnormalities that I will likely never get the chance to see again unless I spend additional time there. I had no idea it was even possible to live with a single ventricle heart, let alone function reasonably well in the world. However, as you might expect, patients with these types of rare and extreme cardiac abnormalities require a high degree of very specialized care from many different practitioners.

I am reminded of one patient in particular that really illustrated this point. We had a patient with a single ventricle heart that had been in the ICU for almost 6 months that was transferred to our service because he had been doing well. I took this patient on as one of my patients, and I have never taken care of a more complex patient before. The needs of this patient were extensive as he had a GJ tube, a trachiostomy tube, and several other needs on top of his cardiac abnormality. On this service we had multidisciplinary rounds that included the physicians, pharmacist, nurse, dietician and social worker, and it was absolutely necessary. It was simply too much to ask for the physician team to manage each of these aspects of the patient’s care; having each individual team member be able to have their own domain to take care of with the physician directing general goals was the only way to really keep straight this patient’s complicated needs. I had to become good at adapting to making my plans not be extremely specific but instead just goals or ideas for the patient and deferring to the appropriate team member to get their opinion as to how best to achieve those goals. If I had to plan out each aspect of this patient’s care myself, it would have taken my entire day and I would not have been able to do as proficient a job as each team member did with their own domain. During this patient’s course, I utilized and communicated with the pharmacist, nurse, dietician, respiratory therapist, social worker, speech and language pathologist, and physical therapist and every single one of their interventions and knowledge was needed to help this infant achieve the best outcome. A goal of mine is to meet and develop a relationship with all of the other care team members such as social work and pharmacy that work in the clinics that I will be working at next year as an intern.

Above: An animation from Nationwide demonstrating the remarkable first stage of the cardiac surgery to fix hypoplastic left heart.