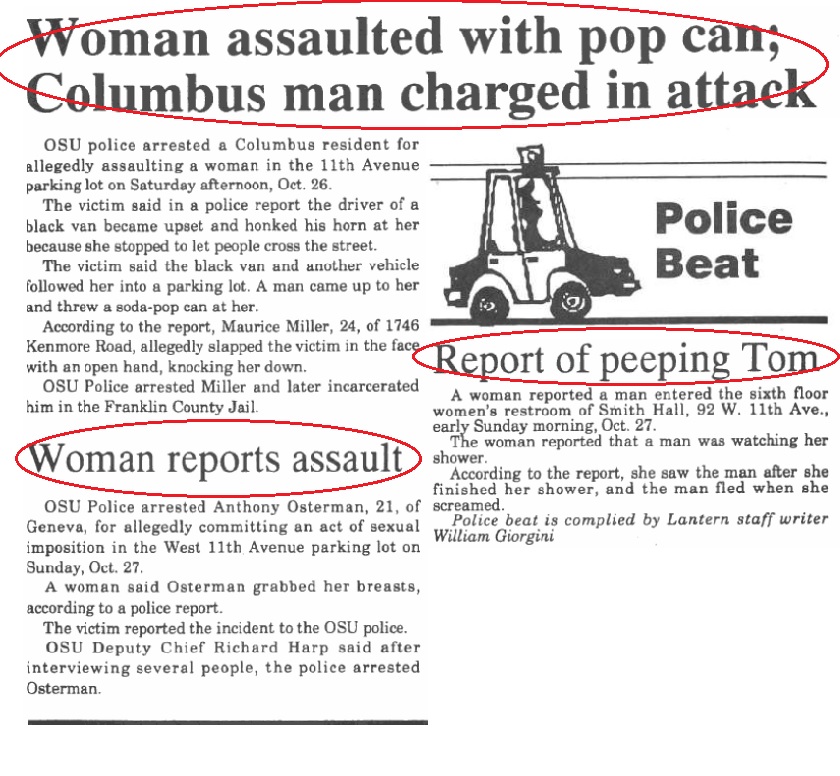

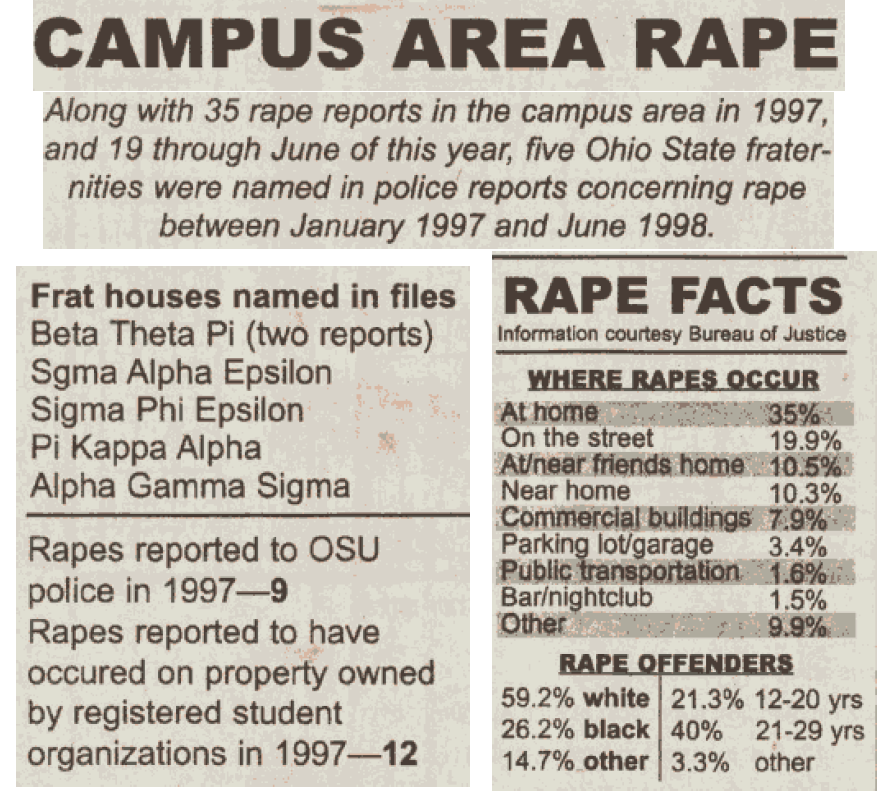

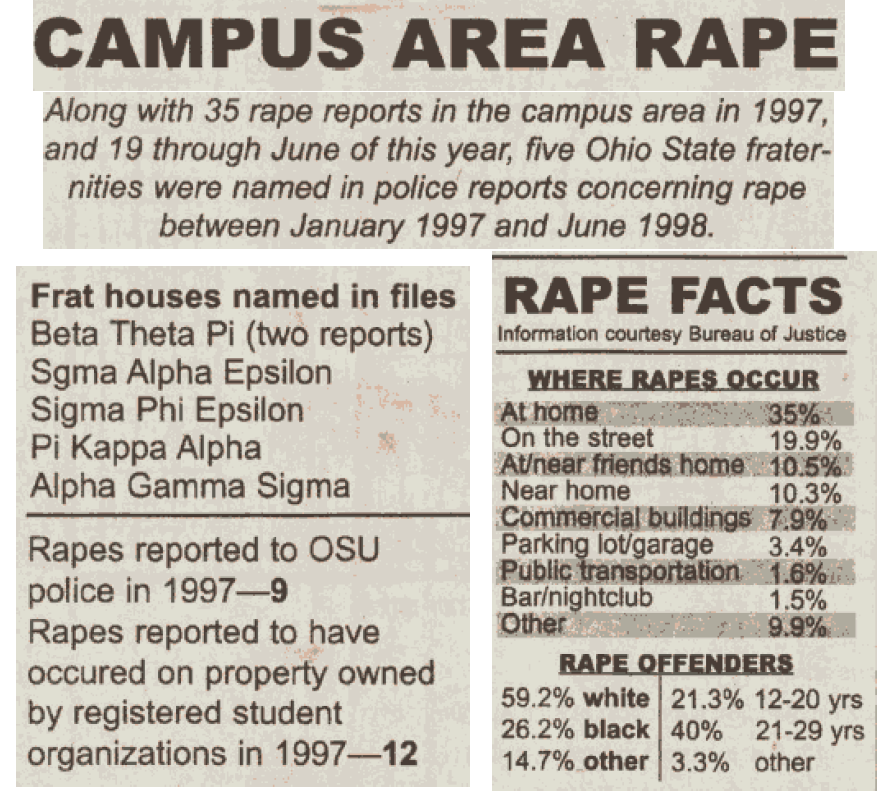

In the August 1998 issue of The Lantern, there were four pieces that covered rape on OSU campus. 3 of the 4 mentioned frat houses and Greek life a part of the issue of rape on campus. The article “Area Rape Risk may be understated by statistics”, reported that 6 rapes in fraternity houses were reported from January of 1997 to August of 1998, but the statistics are misleading because many cases go unreported.¹ A study by the Journal of Interpersonal Violence was cited in the article, which collected information from 32 college campuses and found that 58% of survivors of rape incidences on campus report to anyone, while only 5% report rape to police. Michael Scare, then coordinator of Rape Education and Prevention Program (REPP), said relatively high rates of rape within Greek Life can be partly attributed to the fact any systems on campus that hold high privilege of any kind can often avoid accountability in order to maintain a certain reputation.¹

Statistics featured in the Lantern (1998)¹

What’s more, the emphasis on brotherhood can lead to upholding the “silence code” when rape occurs. There were varying opinions in the piece, but one member of a frat reaffirmed the pervasiveness of the silence code , “It’s not fair that 40 other guys get blamed for one guy’s actions…the smart thing to do is to be silent. You wouldn’t want to trash the kid’s reputation”.¹ Other members of frats denied the silence code, one member said the system “encourages honesty”, and others said the publicity was skewed against them because of their high profile.¹

An article underneath the aforementioned article and adjacent to the statistics graphic above, was titled “Rape Discussions held among campus officials”. This piece reported that “15 officials from various Ohio State departments gathered to talk about sexual assault on campus August 10” and met the same day the article was printed, to discuss improvements in “existing programs and policies for faculty and students”.² The focus was on information on crisis management, prevention, and education. They also discussed information dissemination modes, including University College, residence life, Greek life, and orientation for freshman, who seem to be most vulnerable (this is only now being implemented for freshman recently).²

An editorial, “Silence code hurts efforts to curb rape” in the August 1998 issue criticized the silence code of Greek life, stating “being a ‘brother’ shouldn’t include ignoring [rape] when your supposed ‘sisters’ are being physically assaulted”.³ The editorial also criticizes Deborah Shipper, Michael Scarce successor, for initially withholding the file on fraternity rapes “over fear that she would anger Greek leaders”; the article asserts, it shows how powerful the code of silence is. The article more broadly criticized OSU administration and “good PR” efforts through silencing rape. One way OSU does this is by not including off-campus rapes in the reports, which downplays the numbers and puts students at risk.³

Works Cited

1.Stevens, Elizabeth, and Alison Rasmus. “Area Rape May Be Understated by Statistics.” The Lantern [Columbus] 29 Aug. 1998: 1-2. Print.

2. Stevens, Elizabeth, and Alison Rasmus. “Rape Discussions Held Among Campus Officals.” The Lantern [Columbus] 29 Aug. 1998: 1. Print.

3.Editorial. “Silence Code Hurts Efforts to Curb Rape.” The Lantern [Columbus] 24 Aug. 1998: 4. Print.