Many kinds of mites are associated with insects. Some feed on the insects, while others just hitch a ride. When you work in an insect collection it is not uncommon to find tiny mite “guests” attached to the bodies of our specimens.

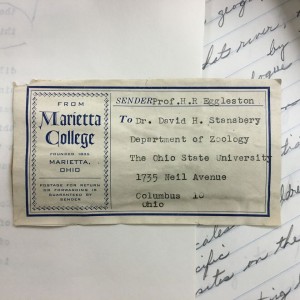

As described in a previous post in this blog, when the OSU Acarology Collection acquired the Asher E. Treat Mite Collection, they received a large number of boxes containing slide-mounted mites and a few oversized Schmidt boxes packed with dry mounted moth specimens. The mites were originally collected on (or in!) these moths.

Asher Treat wrote a whole book about mites and the moths they associate with. Like the mites in the Treat collection, the moths are research vouchers, the specimens that Treat referred to (and even illustrated) in his publications.

As with all research voucher specimens, the Treat moths need to be properly preserved for the future and, when necessary, made available to scientists who might want to examine the specimens. As the Triplehorn Insect Collection is a well-known public research voucher repository, we were asked to hold the Treat moth vouchers. At the time we received them from our colleagues in Acarology, we posted some images in the collection’s Facebook page.

The first stop for the Treat moths was the insect collection -40°C freezer. The extreme cold kills any potential pests that might be hiding with the incoming specimens. These pests, things like carpet beetles (dermestids), eat dead, dried insects, reducing them to a pile of dust. So it’s essential that we do not introduce them into the collection! Later on we gently moved all the moths (and/or pieces of them) to our regular storage trays and drawers. Many of the specimens did not have individual labels attached to them. So to avoid confusion, we transferred the specimens to new trays, but kept them in the exact same organization used by Treat. This whole process took several weeks.

During the initial curation we noticed that many of the moths had detailed labels, including the number and kinds of mites removed from them. Some even mention that they were photographed for a publication. However, other specimens don’t have much information associated with them at all. It’s not clear if those are research vouchers or just regular specimens that Treat had in his collection but did not use for publication.

As we curate the collection further, the confirmed research vouchers will receive voucher labels (green, makes it easy to see them in the collection) and a unique identification number. The specimen label data will be digitized and added to our online database, and finally the specimens will be stored according to the moth group (family, genus, species) they belong to. Besides the specimen label data, we will eventually have images of all vouchers specimens.

I am hoping that as the Acarology collection completes the curation and digitization of the Treat mite specimens, we will have answers to some of our questions regarding the voucher status of the specimens. And since we share the same database platform, xBio:D developed here at the Triplehorn collection, we will be able to easily associate the mite specimens with their moth hosts.

The curation of the Asher Treat moth voucher collection will demand many more hours of work by our student assistants and volunteers.

If insect curation is the kind of activity you think you would like to learn (or maybe you’re already an expert?!), come talk to me! Volunteer some of your time and talent to help us make the Treat moth vouchers available to the world. Volunteers make a tremendous contribution to the collection and, therefore, to science.

If volunteering is not your thing, maybe you will consider making a donation to the C.A. Triplehorn Insect Collection Friends Fund (#314967). Your gift will revert 100% to the collection and support the dedicated students & interns that work in the collection while getting trained to become the biodiversity scientists of the future. Thank you for your interest!

About the Author: Dr. Luciana Musetti is an Entomologist and the current Curator of the Triplehorn Insect Collection.