It’s only mid-January, and the Triplehorn Insect Collection 2016 calendar is already getting crowded. So I started laying out the events and activities that are coming up. Here’s the scoop:

January 29 – Deadline for the 2016 Museum Open House T-Shirt Design Contest

One of the perks of volunteering to help with the Museum Open House is the volunteer t-shirt. Since 2006, volunteers have received a unique t-shirt, designed especially for the year’s event. The t-shirt is both practical (easy to identify the people working on the event) and so very cool (only the people who work in the event have it.)

In 2008, ‘Alien Invaders‘ became the first theme associated with the Museum Open House. T-shirt designs and colors changed over the years. Every volunteer has their preferred t-shirt and many of us take pride in having the complete set of Museum Open House t-shirts.

The theme for the 2016 Museum Open House is Living Colors, addressing the role of colors in nature. This year OSU students are invited to participate of the t-shirt creation process by entering their design idea in the Museum Open House T-Shirt Design Contest. And the winner will get an Apple Watch, plus a t-shirt! Deadline is January 29. There’s still time to participate!

April 23 – Museum Open House #MBDOH2016

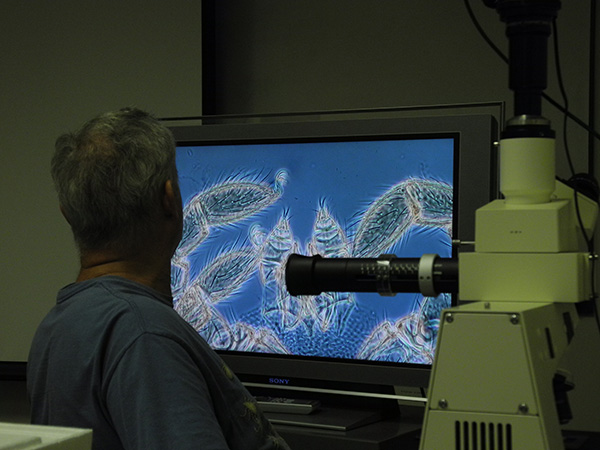

As I mentioned on a previous post, the Museum Open House is getting a face-lift that includes moving to a later date to take advantage of the (hopefully) warmer weather & adding outdoor activities. If the trend continues, we expect to break records again in the number of visitors, and we are trying to prepare for that. Planning for the #MBDOH2016 started back in October 2015, and will pick up speed in the next several weeks. Follow our progress on Facebook and Twitter by using the event’s hashtag. Here are some photos of the Triplehorn collection activities during the Museum Open House. Many more are available on our Facebook photo albums. Check it out!

June 27 to July 1 – Insect Summer Camp

One thing we’ve learned from the Open House is that there are a lot of people, particularly kids, that are just over the top about insects and eager to learn more. To address this need, this summer we’ll have an insect summer camp: a 5-day camp (just during the day, not overnight!) targeted at middle school students. We want to work with the students to help them learn about what insects there are, how they’re put together, what they do (both the good and the bad), and how to make an insect collection. In addition to collecting, we’re arranging interesting visits and other activities. We’re working closely with the Department of Entomology and the Ohio 4-H in developing the camp. Enrollment will be limited, so if you’re interested keep a close watch on the collection’s Facebook page to sign up when the time comes.

September 24-25 – Entomological Collections Network Meeting

The ECN is a long-standing organization dedicated to the support and dissemination of information about and for entomological collections. Membership is open to anyone interested in the subject. Each year the ECN meeting brings together collection curators (like me!), managers, and users from all over the world to discuss community advancements, report on curation and collections-based research projects, etc. ECN meetings are held on the weekend before the Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America.

September 25-30 – XXV International Congress of Entomology

ICE is the premier international event for entomologists and is held every four years. The 2016 event will be hosted by the Entomological Society of America in sunny Orlando, FL. More than 6,000 entomologists from all over the world are expected to participate.

We plan to submit our curatorial and specimen databasing work for presentation at ECN and ICE.

Besides these events, we will continue working on ongoing curatorial projects and activities, mainly:

Beetle Curation — Tenebrionidae specimen databasing: So far we have added 16,383 teneb specimens to the database (mostly between June and December 2015.) That’s roughly 3 of our cabinets, so 7 more to go. Anyone interested in volunteering a few hours a week to help us out is more than welcome!

List of Coleoptera species in the collection: A list may not sound very impressive, but that is a very useful tool for our curatorial staff. It’s also a laborious and tedious task which involves deciphering cryptic handwriting and/or very small typed text (ask Lauralee an Alex about that.) Our very preliminary list of beetles contains about 13,000 species names. Based on our experience with the beetle families that we have already curated, it’s safe to say that our list of beetle species will grow significantly as we inventory the collection.

Incorporation of the Parshall Butterfly Collection — Before we can add the new donation to the general collection, all the specimen boxes and drawers need to be frozen as a preventive pest control measure. Freezing (-20 to -40°C for several days) will kill any live pests that might be hiding in the drawers. As drawers are freeze-treated and added to the general collection, and as time and funds allow, we will be inventorying and cataloging them.

Training personnel — Last year several undergrad student assistants graduated and left. In addition, two of our volunteers and interns concluded their term with us and left as well. By mid-2016 we will go through even more personnel changes as Matt Elder (after 5 years working here with us) and Katherine Beigel both graduate and head out into the world. These two students will be a tough act to follow, but that’s the nature of universities: students graduate. We expect to hire new students in the next few months to be trained and to work on specimen databasing, imaging, and curation in general.

Training of new student assistants takes between 4 to 6 months for those working 10 hours per week. Our newest hires, Martha Drake and Rachel McLaughlin, two Entomology majors that started with us last semester, are back to work after the school break and are making very good progress.

We also have a new volunteer! Jan Nishimura has just joined us this week. Welcome, Jan! She will be receiving training on handling specimens and basic curatorial skills so she can help us accomplish our goals for the year.

Service to the community — Last but not least, we serve the community by providing access to the collection for both study and outreach. We offer qualified individuals the options of borrowing specimens or coming in to examine the specimens here. We can also provide data and images upon request. We welcome groups and individuals, on an appointment basis, for guided tours of the collection.

The new year came full of challenges, but full of possibilities as well. We are embracing it, keeping very busy, and relishing the chance to discover something new or beautiful each and every day.

About the Authors: Dr. Luciana Musetti is an Entomologist and the Curator of the Triplehorn Insect Collection. Dr. Norman Johnson is the Director of the Triplehorn Insect Collection. He made a significant contribution to the post and shares the authorship.