People often remember what they were doing when a historical event occurred. Were you sitting in the living room watching TV when the first man walked on the moon? Were you at work when the Titanic sank?

In the Tetrapod Collection, we often find specimens collected on days of historical importance and here we share some of our favorites with you:

- 3 Jul. 1985. Back to the Future came out, the same day this Rose-Breasted Grosbeak was preserved to last for centuries.

- 8 Sep. 1966. The first episode of Star Trek was released, the same day these Western Banded Geckos were collected.

- 2 Jul. 1962. The first Walmart opened in Rogers, Arkansas, the same day this Fowler’s Toad was captured in Ohio.

- 12 Aug. 1939. The first World Premiere of Wizard of Oz, the same day this Pallid Bat was found.

- 20 Jul. 1969. The first man walked on the Moon, the same day Woodrow Goodpaster walked and found this Red Squirrel.

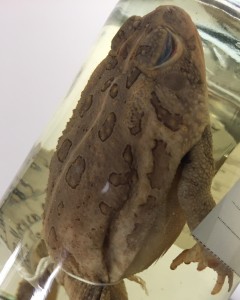

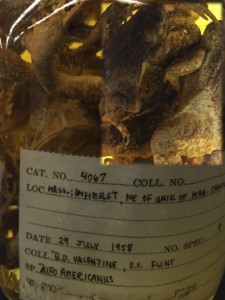

- 29 Jul. 1958. NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) was founded, the same day these American Toads were found.

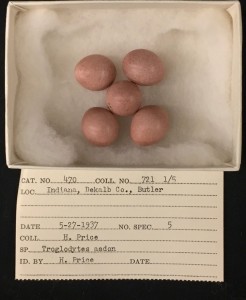

- 27 May 1929. The Golden Gate bridge was opened, the same day these House Wren eggs were collected.

- 1 May 1931. President Hoover turned on the lights for the Opening of the Empire State Building, the same day these Great Blue Heron’s eggs were collected.

- 4 Oct. 1927. Carving of Mt. Rushmore began, the same day a flying squirrel was collected and the skull preserved.

- 1 May 1941. Cheerios were introduced as a breakfast staple, the same day this American Goldfinch was found.

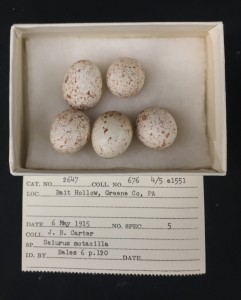

- 6 May 1958. Babe Ruth hits the first of many home runs, the same day these baseball shaped eggs of a Louisiana Waterthrush were found and preserved.

- 16 May 1929. The first Academy Awards were announced on the same day these tiny Carolina Chickadee eggs were collected.

- 21 Mar. 1962. The world greeted the first Taco Bell on the same day as these Spotted Salamanders were collected.

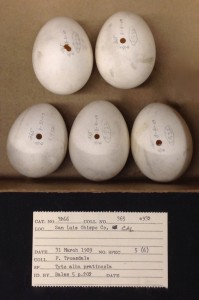

- 31 Mar. 1909. As the Titanic’s construction had just started these Barn Owl eggs were collected.

Photo Credit: Abby Miller, Volunteer in the Tetrapods collection