When you picture a vertebrate collection, you probably think of a collection of taxidermied birds and mammals or jars of pickled fish. But when you actually visit the collection, you will find the typical research study skins, and pelts and – out of necessity- preserved parts of specimens such as jars with tongues, eyes, stomach contents, brains, boxes of horns, eggs, nests, wings etc. These are organized as sub-collections within a vertebrate collection and are known under varying names such as the osteological or oological collections. These “sub-collections” can be used as educational tools, in research projects, or in art classes. But when we salvage or collect a specimen, why don’t we keep the entire specimen? One may argue that a whole specimen would have higher value to a researcher than the bits and pieces found in these sub-collections.

Indeed it is useful to preserve the entire specimen but there are many constraints that vertebrate and other museum collections face that prevent us from keeping an intact specimen.

One big issue museums face is space. For vertebrate collections, though it would be lovely to

A walrus as a whole specimen takes up a large space but when folded up it can fit in a cabinet. (S. Malinich, 2013)

have an entire whale or elephant in the collection, such a specimen would take up a large part of our collection area. If a museum has a whale in its collection it may only keep parts that researchers have requested in the past such as particular vertebrae, a manus, or a partial skull. A great example of this can be found in the AudioVision “Whale Warehouse” video episode. Within the episode, Grant Slater and Mae Ryan, producers for Southern California public radio, explore the L. A. Natural History Museum’s over-sized specimen storage facility, a place where curators store parts of large aquatic mammal specimens. Not only are the specimen parts inside large but they take up an entire warehouse off grounds from the main facility!

Larger birds, such as these Golden Eagles, take up space where hundreds of smaller song birds could fit. (S. Malinich, 2013)

Here at the Museum of Biological Diversity, we do not face the challenge of storing whales, but smaller specimens in large numbers can soon turn into a space problem, too. Over 20 swan specimens, can take up the same cabinet that could be holding over a thousand smaller song birds. This puts constraints on how many specimens of a species we can accession per year and the maximum size of specimens that we can accept.

Another problem museum collections face is the condition of a specimen. Upon receiving specimens we conduct quality checks on varying aspects of the specimen.

First, we conduct a sniff check: if the specimen smells rotten, it is past the point of return and we do not attempt to make it into a study skin, because it would continue to decay at a rapid pace.

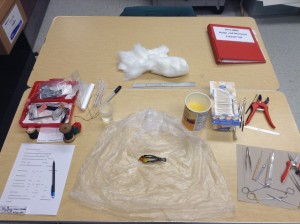

A student prepares a specimen skin. While she prepares it she checks it for any reasons why it could not be made into a full study skin.

Second, we do a visual look over on the outside of the specimen: We look for maggots, large wounds, as well as gangrenous flesh which would prevent us from turning the specimen into a whole study skin.

Third, we consider acceptance of certain specimens over the year. Though

it would be nice to make every specimen we receive into a study skin, we simply cannot fit them all into cabinets. So only the specimens that are clean (or cleanable) and not losing feathers or fur will be preserved as full skins.

Sub-collections may arise because of a researcher’s fascination with a particular feature of a specimen, but they have become important parts of modern collections. Some sub-collections of the Tetrapod Collection are: skeletons, wings, feet, tails or samples of feathers. This way important research material is preserved, but instead of taking up a large portion of a cabinet these specimens can be filed just like documents into filing cabinets. This also makes sure that valuable records of species are kept even though a full skin could not be made because of how they were found when salvaged. These parts collections can still be valuable for research, for example, when scientists need DNA samples of a particular species. New molecular techniques allow extracting DNA from small tissue samples. To make up for the loss of a full skin, we take multiple images and measurements during processing to accompany the specimen in the collection.

Though it would be ideal for museum’s to preserve an entire specimen it may not be possible in the future as museum collections continue to grow. However as science progresses we are finding that even the smallests amounts of tissue samples of specimens can reveal much about a species. Entire collections of just tissue samples are being formed all around the world focusing on specific taxons or groups of species. In the future, as collections continue to grow it will become more beneficial to create more sub-collections with tissue samples to further the research value of museum collections.

About the author: Stephanie Malinich manages the tetrapods collection at the MBD.