There is a symbiotic relationship between springtails and a bacteria known as streptomyces, which is fascinating and scientifically documented. It is related to that lovely scent of earth after it rains, known as petrichor. When the bacteria are dying, they create spores to populate the next generation and they need springtails to spread the spores so they emit the scent to attract springtails. Springtails come for the feast of dying bacteria and leave with spores in their belly and on their skins, spreading them around to new locations. This relationship seems similar to those formed by plants and pollinators, but it is far more ancient. We just did not discover it earlier because it is happening mostly underground, the bacteria are invisible, and springtails are so tiny. More info on this 500 MILLION year old relationship here.

We are not making up these wild stories, just trying to simulate and experience them in our VR experience, Belonging to Soil. In it, you are a springtail, doing your important work of contributing to the soil ecosystem. Eating streptomyces bacteria and spreading their spores is one of the things you will get to do in our VR project. This is a walk through of the chamber of bacteria that are sporulating.

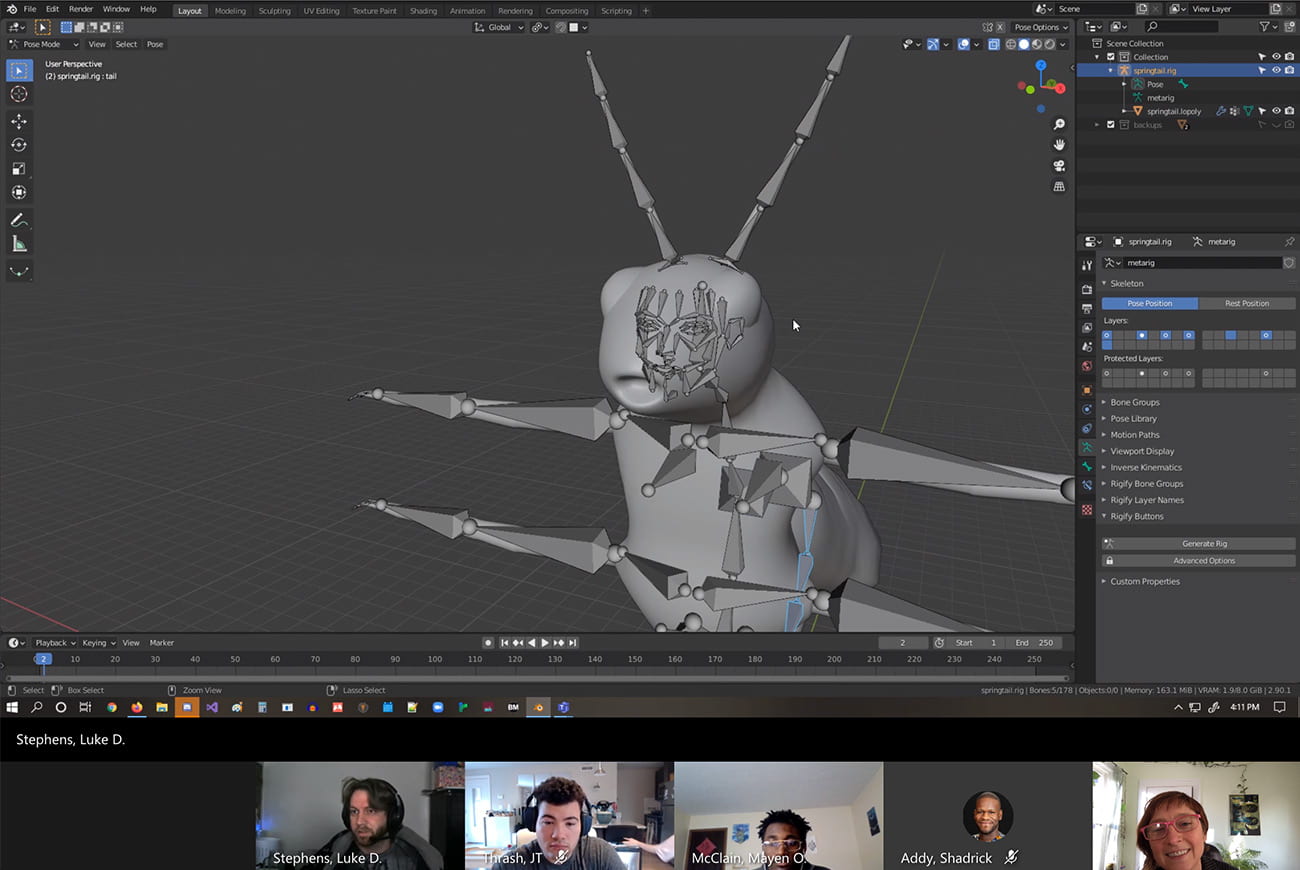

Mayen McClain has been working on the 3D environments, The programming for the interactions are being created by JT Thrash, Andrew Sanchez, and Shadrick Addy. Will Yuan and Megan Wright are working on characters and animation. Amy Youngs is doing the story and project management. We will soon be adding the custom music and sound effects made by Josh Rodenberg.

The new character also has hands, which is not realistic to springtail insects, but since it is a part of the Humanoid Controller they were included.

The new character also has hands, which is not realistic to springtail insects, but since it is a part of the Humanoid Controller they were included.