– Kenny Burdine and Greg Halich, University of Kentucky Agricultural Economists

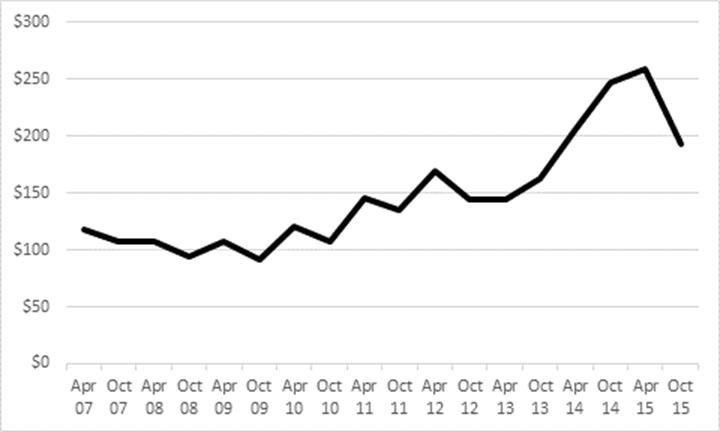

The drastic decline in calf prices from summer 2015 is having a major impact on cow-calf profits. In evaluating cow-calf profitability this year, it may prove useful to provide a long-run perspective on calf prices. The chart below shows historical April and October prices for a 550# steer in Kentucky from 2007 to 2015 (USDA-AMS). Part of our message to cow-calf operators as we traveled the state this winter / spring was that our current market is not that far from the long-run “normal”. Current prices are not bad from a historical perspective. What does look bad are these prices compared to what we have had in the last two years. When you sold calves for $2.00-$2.50/lb just over a year ago, selling those same calves in the $1.35-$1.50/lb range is hard to swallow.

The calf market that we enjoyed for much of 2014 and 2015 reached those unprecedented levels due to an extremely unique set of circumstances. A prolonged drought in the Southern Plains from 2011-2013 and the loss of significant pasture ground to row crop production extended the liquidation phase of the last cattle cycle. Had it not been for those two factors, herd expansion would have likely begun in 2011 or 2012, rather than 2014. The result was that we entered 2014 with a cow-herd about the same size as we had in the early 1960’s. As we began to grow the cow-herd in 2014 and 2015 (through reduced cow slaughter and increased heifer retention), we were also seeing sizeable production increases in pork and poultry. These factors, combined with reductions in exports, left considerably more meat available per capita in the US. This placed a great deal of pressure on cattle prices, which were further depressed as slaughter weights rose due to cheaper feed last fall. Regardless of the causes, the result was as significant a drop in calf prices as we have ever seen on a year-over-year basis. For the first week of August 2016, 550 lb steer calves were selling around $1.45 per lb on a state average basis according to the weekly Kentucky Livestock and Grain Market Report. The same week in 2015, those same steer calves were selling for $2.44 per lb. This 41% price decline represents a difference of nearly $550 per steer in twelve months and that $550 decline was virtually all profit.

Given this drastic drop in prices, it seems fitting to take a look at expected profitability for cow-calf operations in the current market. Table 1 estimates fall 2016 returns to a traditional spring-calving cow-calf operation. Every operation is different, so producers should modify these estimates to fit their situation. Average weaning weight is assumed to be 550 lbs and the steer / heifer average calf price is assumed to be $1.40 per pound, which is just an estimate for this fall. Weaning rate is assumed to be 90%. Using this weaning rate, we effectively convert revenues from a “per calf weaned” basis to a “per cow maintained” basis. It is worth noting that this is a relatively high weaning rate compared to the Kentucky average. Based on these assumptions, calf revenue per cow is $693.

The pasture stocking rate is assumed to be 2 acres per cow-calf unit and pasture maintenance costs are assumed to be relatively small. At $25 per acre, this would include one pasture clipping and seeding some legumes on a portion of the pastures acres each year. Producers who apply fertilizer to pasture ground would likely see much high pasture maintenance costs. Cows are assumed to consume 2.5 tons of hay through the winter and that hay is valued at $75 per ton. In many cases hay can be purchased for less than this, but most operations produce their own hay and costs on many of these farms will be higher. Mineral cost is set at $35 per cow, veterinary / medicine costs $25, trucking costs $10, machinery costs $20 (primarily for feeding hay as this does not include machinery for hay production or pasture clipping as they are included in those respective costs), and other costs $15.

Breeding costs are assumed to be $40 per cow and are one of the most misunderstood costs on a cow calf operation. Breeding cost on a per cow basis should include annual depreciation of the bull and bull maintenance costs, spread across the number of cows he services. For example, if a bull is purchased for $3,500 and is sold two years later for $2,500, the bull depreciated $500 each year. Then, if his maintenance costs were $500 per year (feed, pasture, vet / med, etc.), his ownerships costs are $1,000 per year. If that bull covers 25 cows, breeding cost per cow is $40. A similar approach can be used for AI, but producers should be careful to include multiple rounds of AI for some cows and the ownership costs of a cleanup bull, if one is used.

Marketing costs (commission) are currently assumed to be $27 per cow. Larger operations may market cattle in larger groups and pay lower commission rates, but this assumes 2.5% of value, plus commission, checkoff, and insurance.

Finally, breeding stock depreciation is another key cost that is often overlooked. For example, if the “typical” cow was valued at $1,800 when she entered the herd and a typical cull cow value was $800, then she would depreciate $1,000 over her productive lifetime. If we assume a typical cows has 8 productive years, then annual cow depreciation is $125. This is the assumption made in this analysis, but the actual depreciation will vary across farms. When buying replacement bred heifers, this cost is obvious. With farm-raised replacements, this cost should be the revenue foregone if the heifer had been sold with the other calves, plus all expenses incurred (feed, breeding, pasture rent, etc.) to reach the same stage as a purchased bred heifer. While discussion of costs that are included is important, discussion of costs that are not included is just as crucial. Notice that no value is placed on the time spent working and managing the operation, no depreciation on facilities, equipment, fences, or other capital items is included, and no interest (opportunity cost) is charged on any capital investments including land, facilities, and the cattle themselves. So, the return needs to the thought of as a return to the operator’s time, equipment, facilities, land, and capital. Based on these assumptions, total expenses per cow are roughly $535 and revenues per cow are $693 for a return to land, labor, capital, and management of $158 per cow.

Cow-calf operators should ask themselves if this return adequately compensates them for their time and provides them with a reasonable return on their investment in the operation. For example, if a cow-calf operator wanted to receive a $50 return for their labor and a $50 return on each acre of pasture (2 acres per cow or $100 total) utilized, our analysis would suggest that they would just reach that goal. However, it would leave almost nothing for depreciation /interest of equipment and facilities. As an example, $3000 yearly depreciation and interest on equipment/facilities for a 30 cow operation would be an additional $100 cost per cow. Using this example, the farm would have lost $92 per cow when accounting for all costs.

A quick comparison of estimated 2015 and 2016 returns showcases how drastically profitability has changed. In the previous 2016 estimation, fall prices for 550 lb calves were assumed to be $1.40 this fall. Using the Kentucky Livestock and Grain Market Report for the week ending October 16, 2015, a 550 lb steer / heifer average price would have been around $1.81 per lb. Table 2 provides an estimate of 2015 profitability using this higher price level. Note that most costs are unaffected by the overall market level. Commission was adjusted upward to reflect the higher market prices, but other costs remain the same. One could argue that breeding stock depreciation should be adjusted upward as well, and clearly would be higher if a large number of bred heifers were purchased and added to the herd last year. But, if one takes a long term view and thinks about the average cow in their herd over time, breeding stock depreciation likely changes very little given the market. Note that estimated return to land, labor, and capital was $356 per cow in the fall of 2015. Using the costs for land, labor, and capital from the previous example ($250), this farm would have made a pure profit of $106 per cow.

If our estimates for prices in fall 2016 are close to accurate, that would represent a 23% decrease in calf prices. However, return to land, labor, and capital is project to decrease by more than 56%. Simply put, the decrease in calf prices since last year is almost 100% profit and this is probably a point that has not been made clear enough over the last 12 months. The profit picture for cow-calf operations has changed drastically in a very short amount of time.

We encourage you to go through and modify the above analysis for your situation. However, if you are honest about your costs and have reasonable expectations for what you need for your labor, paying off depreciation and interest on equipment/facilities, a return for pasture rent, etc., we don’t see how anyone is making much or any true profit at current calf prices.

There was a Progressive Farmer article that came out about a half-year ago where the beef producer interviewed said they still saw good profit potential with the current market at the time and that they planned to continue expanding their cow herd. While we certainly don’t see those profits, particularly at the slightly lower prices of late summer 2016, if enough cow calf operators think profits are still there and continue to expand the national herd, calf prices will continue to drop further. Trying to improve profitability in 2016 by expanding the cow herd is akin to trying to put out a brush fire with gasoline. Hopefully producers realize this and the current phase of cow expansion has already ended.