Today was a visit to Vestmannaeyjar, or the Westman Islands, an archipelago of 15 small rocky islands formed by volcanoes off the southern coast of Iceland. Only one island — Heimaey, or Home Island – is populated, with about 4,000 people. Its main industry has been fishing, but tourism is taking over.

To get to Heimaey Island we took a 40-minute ferry from Landeyjahöfn. Before this harbor was built, people had to take a three-hour boat ride from Reykjavik. The harbor is next to where the glacial river Markarfljot flows into the ocean, and extensive work had to be done to keep the river from eroding away the sand plain. Now that people can visit the Westman Islands on a day trip, tourism has boomed.

After disembarking the ferry, we started to walk around town. A car is not needed because it’s so small, but there are some steep hills. The main story of Home Island revolves around the 1973 eruption of Eldfell volcano, a natural disaster that lasted for months, destroyed many homes, and caused many people to leave the island. We walked on a street where homes had been buried by lava and never dug out. Grass was growing where the roof should have been, with only part of the front door visible.

Volcano museum

The volcano eruption of 1973 is so important to the history of the area that Heimaey Island is known as the “Pompeii of the North.” People had no warning of the eruption, but they were lucky because the weather that day was bad so the fishing boats were still in the harbor. Most of the town’s inhabitants ran to the boats with whatever they could carry and went to the mainland. Many never returned.

The island’s experience during these events is memorialized at the Eldheimar Volcano Museum, which was our first stop. It was a long walk up a steep hill, and the weather was as bad the day we visited as it might have been the day the volcano erupted. I was carrying a heavy backpack walking in extreme wind and had forgotten my new scarf, so it took me a long time to get there. I was relieved when I finally did.

At the center of the museum is an actual house that had been buried by ash but dug out so visitors can see the effect the disaster had on everyday life. Behind the house an introductory movie was playing that depicted the days, weeks, and months after the volcano erupted, and all the frustrations and disagreements in trying to work with local and national authorities to slow the lava flow and clean up.

It reminded me a lot of all the frustrations and miscommunication around trying to clean up after Hurricane Katrina in the United States. This was a true natural disaster for the people, altering many of their lives forever. Many of them left for the mainland and never went back. Many of them spent months if not years putting their lives back together. Most people lost everything, if not from the volcano itself, then from efforts to get their belongings off the island and ruining them in the process.

One thing I looked for after witnessing events of Katrina is what happened to the animals. We know from Katrina that many people won’t evacuate during a disaster if they have to leave their pets or livestock behind. The museum display mentioned one person leaving with his cat and another with a parakeet. It also mentioned the town herding the cows into a fish factory but putting them down because there was nothing to feed them.

After Katrina, Congress passed the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act (PETS) Act requiring disaster rescues to allow people to bring their pets, but livestock is a different issue. I hope we can start figuring out how to care for livestock better in a disaster. For example, in the case of this volcano, perhaps the cows could have been transported to the mainland on a fishing boat and sold or housed temporarily on someone’s land.

Here are some highlights from the museum’s display:

January 23, 1973 – Eruption begins. Almost 5000 people were evacuated, with the sick and elderly first. People left with whatever they could carry – their cigarettes, a cat, a parakeet, their books. Children still wore pajamas. Boats were overcrowded with 50 to 400 passengers, but people still felt lucky because the fishing boats were still in the harbor.

Lava flowed from the volcano for months. For the first few weeks the disaster made international news. Flights went in and out of the small airport on the island. The town was like a war zone with fire and ash raining down. Locals went into rescue mode. They took people’s belongings to harbor to be loaded on boats and taken to Reykjavik. Cupboards were carried out with things still in them, even coffee still brewing. Perhaps as many items were destroyed during the evacuation as were actually rescued.

At one point toxic gas began coming out of the crater. One man died, as did birds and animals. Then a big chunk of lava broke off from the main volcano fissure and threatened the harbor. If lava destroyed the harbor, the island would become inhabitable. Town residents debated what to do. They consulted experts, one of whom told them to abandon the island. Finally they tried pumping sea water through fire hoses to slow down lava. They didn’t know if that would work, but it did help.

Finally on July 3, the eruption was over. It had lasted six months. Volunteers came from all over the world to help the island residents dig out and rebuild. 800,000 tons of ash and tephra were cleared out, with 1200 truckloads of ash carried out each day. The town cemetery was dug out by hand.

The disaster is still the largest emergency evacuation of people in Iceland’s history. Although most residents eventually returned, one-third never did because their homes had been buried. There was no warning at the time because we didn’t have the technology to monitor what is going on below earth’s crust. Now we can detect warning signs better and take action sooner.

Natural History Museum

Lunch was at a restaurant called Gott. They had an excellent menu with good vegetarian options including an African stew. After lunch we visited the Sæheimar Natural History Museum and Aquarium.

The museum was divided into one side for geology and one for birds and fish. The geology room displayed a lot of rocks and geodes. Most of the signage is in Icelandic. The rooms for birds and fish displayed a lot of stuffed and mounted animals. Then there was an entire room of aquariums, some quite large, featuring a huge variety of live fish and sea creatures.

The best thing was its rescue puffin, Toti. He was found at one-week old and brought to the museum. He is now five. He doesn’t fly but he does have a pool in the back that he can dive into. He also knows the difference between the people who work at the museum and the general public.

Swimming pool

Next came the funnest part of the day, a stop at the Westman Islands swimming pool. One reason my backpack was heavy is that I had brought my swim stuff, but it was worth it. This pool is named one of the top pools in Iceland, and we saw why. Water in the indoor lap pool is mixed with sea water making it easier to float and swim and a more natural experience. Outside were small pools, several hot tubs of various temperatures, and two pretty amazing water slides.

Iceland knows how to do swimming pools right. As a user of swimming pools across the United States, I have swum in more than my share of dirty and even disgusting pools. Americans simply will not shower before getting in the pool, and they will not wear swim caps or hair nets. As a result, many pools are full of a lot of dirt, body products such as lotion, deodorant, and powder, and floating hair both loose and in clumps. The university pool is better because there are fewer little kids peering in the pool, and people who swim laps tend to use swim caps. The Y pool is okay in the mornings but awful by afternoon.

In the United States, swimming facilities manage all this by dumping a bunch of chemicals into the water. This is terrible for your skin – I have to constantly use lotion and even then my skin still itches. In Iceland people are required to take warm soapy naked showers before getting into the pool, and this convention is enforced. This keeps the pool much cleaner and healthier with fewer chemicals.

The day we visited was windy and rainy, but even so we all took advantage of the outdoor hot tubs. The guys started on the water slides immediately with the rest of us watching, but I was itching to try it too. Finally I did it. First was the long triple white slide into a cooler pool – the slide was super fast and the cool water a shock to the system, but it was fun. Next was a shorter and slower red slide into a warmer pool, which was also plenty fast for me.

After a break to warm up in the 42C hot tub, I got my nerve up to try the largest slide, a combination tube and slide into the cool pool. I went up to the top with Lauren, the other older than average student in the group. Of course everyone was watching, so I let a couple of other people go after Lauren went. Finally I said a little prayer, made sure my legs were straight in front if of me with my toes pointed – and I was off. The tube was fast, and I barely remember going on the slide part before hitting the water. When I came up, people were cheering, and Lauren was waiting at the bottom. We hugged each other and pumped our fists. It was good to be 53 years old and still able to slide with the best of them.

After the slides, I got in several laps, then tried some diving in the indoor pool. Then we showered up and headed to the dock to catch the 6:30 p.m. ferry back. If anything the weather had gotten even worse, and the boat was rocking back and forth. Even so, I went with Tobba and Andy to the top deck. Tobba had spent much of the time she worked with Keiko in the bay at Heimaey Island, and pointed out to us where this had taken place. I got soaked before going inside and tried to keep from being seasick. Fortunately it was a short trip, and soon we were in the bus and headed back to Lax-a for the night.

Here are more photos that I took on the island including some of the very cute houses. Click on any photo to enlarge it:

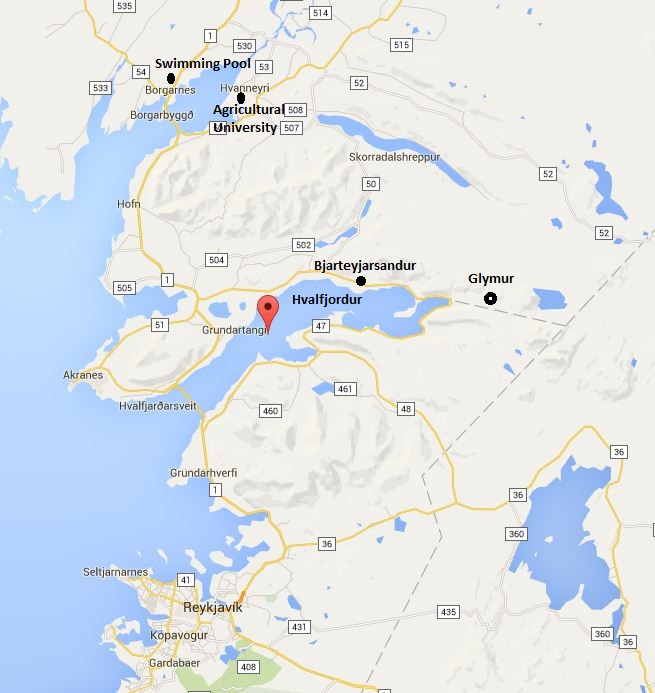

- Map of Heimaey Island

- Boarding the ferry

- Entering the harbor of Heimaey Island

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Island house

- Cemetery

- Island street

- City Hall

- Sculpture in center of town

- Arnar Drang house, home of the Red Cross

- Geological map of Iceland in the Natural History Museum

- Toti napping