This is a reaction to readings in ENR 8150 Advanced Environment, Risk, and Decision Making. The readings were Ch. 10 and 11, pp. 107-130, in Plous, S., The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making (McGraw Hill, 1993), and Keller, C, Siegrist, M, Gutscher, H., The role of the affect and availability heuristics in risk communication (Risk Analysis, 2006, 26(3), pp. 631-639).

Continuing with the theme of trying to apply these readings to climate change communication … surveys repeatedly show that most people perceive the risk of climate change as much lower than scientists say it is. Plous had some good explanations for this in his discussion of the availability heuristic.

One element was imagination: conditions that are easy to imagine were rated as riskier than conditions that are hard to imagine. Climate change falls into the hard to imagine camp for several reasons.

First, it is unprecedented, so it’s not something that has happened to many people. Not many people have told stories of living through climate change, unless you count stories of living through major floods or storms, and those aren’t so much directly caused by climate change as made worse by climate change. There is debate about this. What we haven’t seen yet is large scale migration of populations due to water sources drying up, for example. Once we have more stories of people having to cope with climate change, maybe it will become more concrete. However, of course then it will be too late to do much about it.

Second is how scientists talk about climate change. Usually it is in abstract terms like “desertification,” “acidification,” or my favorite, “dustbowlification.” I mean, who comes up with these words?? They also tend to use a lot of probabilities. The IPCC reports constantly refer to 95% certainty, high confidence, etc. for the findings they are presenting and predictions they are making. Although this is important to how statistically significant the findings are, this kind of language doesn’t make much sense to the average reader. It doesn’t stick.

Related to imagination is vividness. The more concrete and vivid a scenario is, the more people will see it as a high risk. Yet scientists write in such a way as to wipe out practically any vestige of vividness. Take this conclusion from a study on impacts of ocean acidification on marine life: “Sufficient information exists to state with certainty that deleterious impacts on some marine species are unavoidable, and that substantial alteration of marine ecosystems is likely over the next century.” Wouldn’t it be a lot more vivid to say that if ocean pH levels continue to fall at the current rate, the shelled plankton that make up the base of the food web for all life on earth are likely to dissolve by 2100? This kind of vividness is the strategy used by lawyers to win trials, yet it would be practically sacrilege for a scientist to do the same.

Keller’s study illustrates and develops several of Plous’s concepts, and shows why the availability heuristic works: because it attaches to affect. Affect as we’ve seen before is what grabs people because it is processed first through the autonomic system and influences cognition. Affect, not cognition, is what brings about action, and the Keller paper explores several ways to do this.

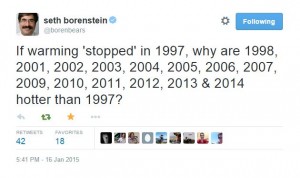

One lesson from Keller’s findings is that frequencies trump probabilities, unless they are very low. For example, people rated the 100-year flood motif as lower risk than a 33% probability in 40 years — yet discussion of extreme weather events almost always frames them as 100-year floods now occurring more often. Perhaps it would be better to frame them in terms of a strong likelihood in 40 years, which is a number in most adults’ living memory.

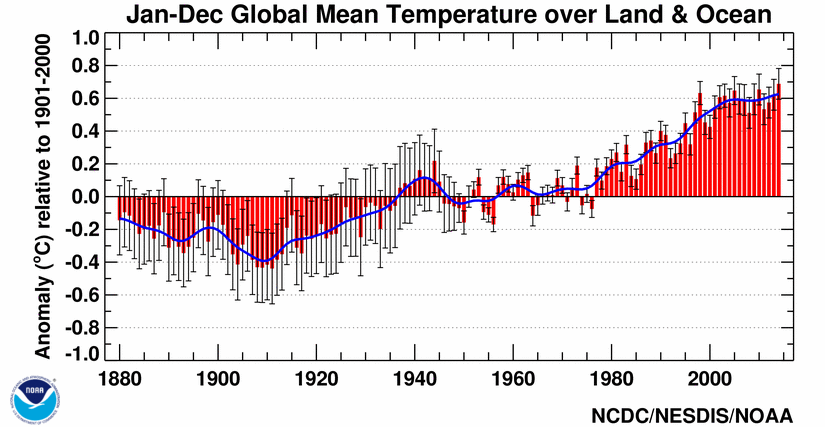

Past experience was also found to have a significant effect on perceptions of risk from flooding. However, as mentioned previously, very few people have directly experienced climate change in a way that’s as tangible as a flood, so this won’t really work there. What could work, based on Keller’s research, is photos and vivid graphics. The graphics would have to be much more vivid than the simply pie charts that Keller’s experiment presented, as those actually decreased risk perception. Good photos could also work.

Here are some examples that I think do a pretty good job:

- NASA posted two videos this week showing what we can expect over the next century for drought in the Western United States and Mexico under a business as usual vs moderate emissions scenario. The moderate scenario is bad enough, but business as usual emissions would pretty much wipe out all life in these regions.

- A recent story on new satellite measurements of ocean acidification included a global map that showed acidification pretty vividly. Satellite measurements are new and allow us to see whole swaths of the ocean rather than taking readings at a few specific points.

- Last summer, several news outlets ran some incredible before and after photos of how lakes in California have been affected by drought. I don’t see how anyone could look at these and dismiss the possibility of climate change.