Intro

To begin this module on Lithuanian culture, please watch a 25-min film: Lithuania (Europe) Vacation Travel Video Guide .

Geography and Language

Lithuania is the largest and most populous of the three Baltic states. It is bordered by Belarus, Latvia, Poland, and Russia (Kaliningrad) and it shares a maritime border with Sweden. Lithuania covers an area of 65.300 km² (about 25, 200 square miles), making it slightly smaller than half the size of Greece or slightly larger than West Virginia. The Baltic coastal area is covered by a so-called maritime depression. The sand dunes create a beautiful coastline. The Curonian Lagoon (Lithuanian: Kuršiu Marios), almost cut off from the sea by the Curonian Spit, a thin 60-mile (100-km) sandspit, is a distinctive feature. It is bounded by the Zemaiciai Upland to the east, which gives way to the flat expanses of the Middle Lithuanian Lowland. Lithuanian rivers drain into the Baltic Sea. The Neman River (Nemunas), cutting north and then west through the country, is the largest. Lithuania has about 3,000 lakes, mostly in the east and southeast of the country. Swampy regions produce large quantities of peat that, dried by air, are used in both industry and agriculture. Lithuanian soils range from sandy to heavy clay. In the northwest, the soil is either loamy or sandy (and sometimes marshy) and is quite heavily podzolized, or leached out. In the central region, weakly podzolized loamy peats predominate, and it is there that the most fertile, and hence most cultivated, soils are found. In the southeast, there are sandy soils, somewhat loamy and moderately podzolized. Sandy soils in fact cover one-fourth of Lithuania and most of these areas are blanketed by woodlands. The climate of the country is transitional between the maritime type of western Europe and the continental type found farther east. Baltic Sea influences dominate the Lithuanian coastal zone. January, the coldest month, could be as cold as in the low 20s F (about −5 °C), and July, the warmest month, has an average of the 60s F (about 17 °C). Rainfalls reach their peak in August, except in the seashore areas, where they happen two months later. Lithuanian vegetation falls into three separate regions. In the marine regions, pine forests dominate while wild rye and various bushy plants grow on the sand dunes. Spruce trees grow in the hilly eastern portion. The central part holds large tracts of oak trees, birch forests, alder, and aspen groves. Wildlife includes wolves, foxes, otters, badgers, ermine, wild boars, and many rodents. There are elk, stags, deer, beavers, mink, and water rats. Lithuania is also home to hundreds of species of birds, among them are white storks, ducks, geese, swans, cormorants, herons, and hawks.

In 2019 Lithuania had a population of 2.794 million people, with Vilnius as its capital and the largest city. The official language is Lithuanian. Linguists are particularly interested in Lithuanian because it is considered to be one of the oldest surviving Indo-European languages. Lithuanian has over 3 million speakers worldwide, with the majority of them living in Lithuania. The language preserves many archaic features, which are believed to have been present in the early stages of the Proto-Indo-European language. Lithuanian is as archaic in many of its forms as Sanskrit, a classical Indian language, which also evolved from the Proto-Indo-European language. However, there are Lithuanian communities in the UK, USA, Spain, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and Uruguay (1).

Unlike Estonia and Latvia, which are smaller states, by the end of the 14th century Lithuania was the largest country in Europe. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania included Belarus and western Ukraine and became one of the most influential powers in Eastern Europe (14th–16th century). Pressured by the Teutonic and Livonian Knights, the Lithuanian tribes united under Mindaugas (d. 1263). A strong grand duchy was formed during the reign of Gediminas (reigned 1316–41), who stretched Lithuanian borders across the upper Dvina River in the northeast to the Dnieper River in the southeast and to the Pripet Marshes in the south. The legend of the great King Gediminas is known to every Lithuanian child.

“The Legend of the Iron Wolf: According to the legend, centuries ago Grand Duke Gediminas was on a hunting trip in the forests of Sventaragis valley around the mouth of the River Vilnia. When night fell, the party, feeling tired after a long and successful hunt, decided to set up camp and spend the night there. While he was asleep, Gediminas had an unusual dream in which he saw an iron wolf at the top of the mountain where he had killed a European bison that day. The iron wolf was standing on the top of a hill with its head raised proudly towards the moon, howling as loud as a hundred wolves. Awakened by the rays of the rising sun, the Duke remembered his strange dream and consulted the pagan priest Lizdeika about it. He told the Duke that the dream was a direction to erect a city among these hills. The howling of the wolf, explained the priest, represented the fame of the future city: that city will be the capital of Lithuanian lands, and its reputation would spread far and wide, as far as the howling of the mysterious wolf…” (2).

Knowledge Check

- How would you describe the difference in climate between the three states, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania?

- How does the Lithuanian language differ from Estonian?

- How did Lithuanian medieval history affect contemporary Lithuanians’ understanding of their past, present, and future?

History

In the 13th and early 14th centuries, polytheistic Lithuania maintained great religious tolerance. It was a friendly state, which allowed for practicing Catholicism, Russian Orthodoxism, and Judaism. The Commonwealth had been the home of the majority of the world’s Jews, with almost two hundred thousand living in the Grand Duchy. During the twilight years of the Commonwealth, Vilnius developed a reputation as an important religious and cultural center for Eastern European Jews. Only in 1385, under the Teutonic Knights’ pressure, the grand duke Jogaila (reigned 1377–1434) agreed to convert to the Roman Catholic faith, married a Polish queen, united Poland and Lithuania, and became King of Poland. Jogaila took the Polish name Wladyslaw II Jagiello. One of his greatest educational and cultural deeds was the reestablishment of one of the oldest European universities, Krakow University. It was founded by Cazimir the Great in 1364, but ceased to exist after the latter’s death, and was reopened by Wladyslaw II Jagiello. In honor of him, the University was named Jagiellonian. Queen Jadwiga, who died a year earlier, contributed part of her estate to the university (3). In 1410 Lithuania, led by Vytautas and supported by Poland, defeated the Teutonic Knights (Battle of Tannenberg). After Vytautas’ death (1430), Lithuania, technically subordinate to the Polish king, had its own rulers and maintained its autonomy. The authority of the Grand Duke gradually declined: the Tatars continually raided its southern lands, Muscovy annexed the principalities of Novgorod (1479) and Tver (1485) and seized one-third of Lithuania’s Russian lands (1499–1503). During the 16th century’s Livonian War (1558–83), Lithuania asked Poland for help. The Poles agreed on the condition that the two states would be formally united. Under the terms of the Union of Lublin (1569), Lithuania officially remained a distinct state and an equal partner with Poland in a Polish-Lithuanian confederation (4). In the late 18th century (1772-1795), the country was completely partitioned by Prussia, Austria, and Russia, with the main Lithuanian area falling under the jurisdiction of the Russian Empire. After two unsuccessful attempts to restore Poland-Lithuania as a state (1831 and 1863), the Russians banned the Lithuanian language and repressed the Catholic Church. Thus, in 1832 the University of Vilnius, founded in 1579, was closed. In 1840 the Lithuanian legal code, which dated back to the 16th century, was abolished. After the second revolt in 1863, the policy of Russification was extended to all areas of public life, and Russian became the only language approved for public use, including education. Books and magazines in the Lithuanian language were permitted to be printed only in the Cyrillic (Russian) alphabet. Such cultural policies triggered national resistance. Books in Russian were boycotted, while Lithuanian publications in the Latin script, printed mostly across the German border in neighboring East Prussia, were smuggled into the country in large numbers.

Watch a 32 min film The Book Smuggler (Lithuanian with English subtitles).

The National Revival declared Lithuanian independence from both Russia and Poland as their major objective. The restoration of statehood finally became possible after both the crumbling Russian Empire and the Germans surrendered in World War I (5).

Folklore and Religion

Lithuania converted to Christianity in 1387, about 4-5 centuries later than other Baltic provinces. Thus, many elements of Lithuanian paganism have survived until today and traces can be found in various artistic forms, from painting to music and theatre. Lithuanian mythology and folklore are thoroughly intertwined with a polytheistic pagan religion. Some pagan deities at some point were transformed into mythical creatures in later folktales and peacefully coexisted with Catholicism. “Paganism in Lithuania was curiously–and perhaps preternaturally– resilient. Notably, it persisted in the wilder regions of the Baltic state until the eighteenth century” (6). Russian 12th and 13th-century chronicles are the best sources of information about the Lithuanian gods, rites, and mythological creatures. The stories about God Perunas, similar to Zeus (Perun in Russia), Zvoruna, who would appear in the shape of a female dog, Medeina, the forest goddess, were worshipped by peasants. In these chronicles, we can find descriptions of Lithuanian customs, among them – a depiction of the ritual to burn their dead (7). The fire ritual has been chronicled as one of the most important Baltic rites. The ritual is often held to commemorate special occasions and is an essential component of many holidays. The aukuras (altar) is erected at a sacred, outdoor site, and participants wash their hands and faces as they gather. A group of people leads the congregants in singing dainas–ancient spiritual hymns–as the fire is lit and the ritual progresses (8). A Lithuanian national Renaissance in the 19th century provided an additional stimulus to the exploration and collection of all the basic genres of Lithuanian folklore. The most comprehensive works were the collections by Jonas Basanavicius, published in Chicago in 1903-1904: From the Life of Souls and Devils and four volumes of Lithuanian folktales (Lietuviskos pasakos) (9).

Although a predominantly Catholic country, Lithuania never parted with its poeticized paganism, which resurfaced with the enthusiasm of new followers in the 1930s. The studies of folklore were further empowered after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the creation of the independent Lithuanian State: “the pagan demi-gods of folklore were also extracted from pagan legends and inserted into an actual national past” (10).

At the beginning of the 20th century, Romuva was recognized as a significant, distinct Baltic faith in the works by Vydūnas. In light of the ideas of J. Basanavičius, J. G. Beržauskis-Klausutis, and others, the institutions of the Baltic faith were reestablished in pre-war, independent Lithuania. The community of Romuva was formed in 1930. During the pre-WWII period of the Republic of Lithuania, the recognition of Romuva as an institution was halted by the Catholic Church. During the Soviet period, Romuva worshippers had to conceal their religious aspirations and celebrate only the folkloric aspects of religious rituals. Finally in 1992 Romuva was officially registered as a Baltic faith community for the first time, but is still not fully recognized today (11). Nevertheless, in 2019, the Lithuanian Parliament rejected the proposal to make Romuva an officially recognized Lithuanian religion. The President of the European Congress of Ethnic Religions wrote in response:

“As president of the European Congress of Ethnic Religions (ECER), I would like to condemn, in the strongest possible terms, the unwillingness of the Lithuanian Parliament (Seimas) to recognize Romuva as an official religion in Lithuania. Romuva has fulfilled all the requirements to qualify for such a designation — it is a rapidly growing religion, whose members have creditably represented their homeland all over the world. Moreover, Romuva stands as one of the few remaining examples of the survival of European indigenous religions and cultures. The decision by the Seimas, under strong pressure from the Roman Catholic Church, represents not only a gross violation of the Lithuanian Constitution but also contravenes important treaties and agreements such as the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (12).

Knowledge Check

- Explain the reasons for religious tolerance in the pre-Christian Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

- How do you understand the correlation between Lithuanian folklore and paganistic religion?

- Describe the Romuva religion and explain why it is popular in Lithuania.

The Movement for an Independent Lithuania

At the beginning of the 20th century, unlike Estonia and Latvia, Lithuania remained a largely agrarian country. It had neither a greatly developed middle class nor a city proletariat. The anti-Russian sentiment in the heavily populated rural areas inspired massive emigration to the U.S. and Canada. On the eve of WWI, “one out of every three Lithuanians lived in North America” (13). In October 1905 the wave of political strikes reached Lithuania as well. On October 15 workers at the electrical station and the Berlin gas works started their strike in Vilnius. On the following day, about 3,000 railroad workers joined them. During the clashes of October 16th and 17th, twenty-four demonstrators were killed in the streets of Vilnius and 132 were injured, many seriously. The funerals of the dead strikers turned into massive demonstrations, in which thousands of Lithuanians participated (14). In December 1905, in Vilnius, 2,000 delegates met at the National Lithuanian Congress, voting for the centralized administration of the ethnic Lithuanian regions and the use of the Lithuanian language in administration and education. The end of national press restrictions enabled “especially pronounced cultural development in Lithuania” (15). With the beginning of WWI, Lithuania, as well as the two other Baltic regions, fell into chaos. As Kausekamp wrote, “three hundred thousand people fled or were evacuated from Lithuania to the interior of Russia” (16). By 1918, “thousands of farms were destroyed, causing many to abandon their homes and flee to the forests, where they lived under very primitive conditions…” (17). The situation was further complicated by the abdication of Nicholas II and the formation of the Russian Provisional Government in Petrograd (renamed St. Petersburg at the beginning of WWI) in March 1917. Estonians petitioned for independence and organized peaceful demonstrations in support of the motion in Petrograd. Their petition was granted. On the contrary, the Lithuanian appeal for the county’s autonomy was rejected by the Provisional Government. The Germans, who still occupied Lithuania, supported Lithuanians’ struggle for independence, and in December 1917, a short-lived independent state was formed, with the German Catholic duke chosen to be its King Mindaugas II. On March 3, 1918, the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty between Soviet Russia and Germany was signed and in early November the Lithuanian Teryba (a 20-member Council of Lithuania, created in 1917) annulled the election of the king. On November 11, 1918, the first government of independent Lithuania was appointed with Augustinas Voldemarus (1883-1942) at the head, but the war for independence was far from over. The Russian Federation, headed by Lenin, disregarded the Brest-Litovsk treaty immediately after Germany capitulated, and the Red Army invaded Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. “The Bolsheviks immediately proclaimed the nationalization of the lands and creation of collective farms… This was contrary to the Baltic dream of every peasant owning his own family land” (18). In this confusing series of military conflicts between 1918 and 1920, the alliances changed swiftly, whether between the Lithuanians and the Russian Red Army against the Polish Army, the Lithuanians and the Russian White Army against the Red Army, etc. The Lithuanian battles with Poland in the autumn of 1920 ended with the loss of the old Lithuanian capital Vilnius, which became Polish. The calls to liberate Vilnius from the Poles included proclamations, posters, cards, post stamps, painted pastel portraits, and written poems, unifying the Lithuanians in the slogan “Mes be Vilniaus nenurimsime” (we will not settle down without Vilnius). Only in 1922, due to the dispute between Lithuania and Poland over Vilnius, did the League of Nations recognize Lithuania by law. Vilnius was restored to Lithuania on October 10, 1939 (19).

Knowledge Check

- Why did so many Lithuanian peasants emigrate to the U.S. and Canada after the 1905 revolution?

- When and where did the delegates of the National Lithuanian Congress meet? What were their demands?

- Describe the hardships that Lithuania suffered during WWI.

Years of Independence, 1918-1940

Lithuania had some remarkable achievements in education during the period of 1918–1940. Starting in 1924, Lithuanian Middle and High Schools (called gymnasia) enhanced the teaching of mathematics, natural sciences, and foreign languages. In the 1930s, the craft, merchant, and other professional schools were established in the country. In 1922, universities reopened, but since Vilnius was a part of Poland, a new University of Lithuania was opened in Kaunas. Illiteracy was successfully eliminated during the first two decades of independence (20). The first Lithuanian Song festival “Dainų diena” (Day of Songs) was organized in Kaunas from August 23-25, 1924. It coincided with the Lithuanian Agricultural and Industrial Exhibition, also held in Kaunas. The second Song festival was dedicated to the 10th Anniversary of the Independence of Lithuania and was held in Kaunas in July 1928, and it was attended by 6,000 singers. Theatre, as a tool of social and political critique, played an important role in shaping national identity. After the first Global Congress of Lithuanians in Kaunas, the Lithuanian Painters’ Association was established in 1935. Among the first museums that were opened after Lithuania became independent was the museum dedicated to Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis.

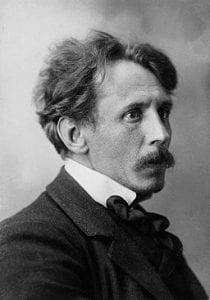

Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionis (1875-1911), Lithuanian artist and composer.

Born in a town that was then part of the Russian empire in 1875, Ciurlionis (pronounced CHOORL-YONIS) started his piano studies, including composition, in Warsaw in 1894. He composed piano fugues and variations, sonatas, a string quartet, and a cantata for choir and orchestra. From 1902 to early 1904, he also attended the Warsaw School of Drawing. Although his first language was Polish, he learned the Lithuanian language. Feeling as a Lithuanian to the core, he returned to Lithuania, and adopted Lithuanian culture. Today he is considered a Lithuanian national icon (21). “During his short life, Ciurlionis managed to be at the heart of the creation of the Lithuanian Artists Union and actively organized and participated in the first three exhibitions of Lithuanian artists, organized and directed Lithuanian choruses in Warsaw, Vilnius, and St. Petersburg, and was the first Lithuanian professional composer not only to take interest in Lithuanian folk songs but to collect and publish them” (22). His passionate love for Lithuania might explain his refusal to teach at the Warsaw Institute of Music. He wrote to his brother that he wanted to dedicate his entire life to Lithuania. As Rasa Andriušytė-Žukienė wrote, “Ciurlionis’ painting is a very important affidavit of the level of modernity of Lithuanian art in the early 20th century. In his painting, his experience as a composer, symbolist visions, and art nouveau insights amalgamated into a unique artistic phenomenon encoding the germs of some of the European Modernist trends. …Yet, Ciurlionis … was especially close to one particular trend in Symbolism, which spread across Russia, Poland, and Scandinavia, pursuing the metaphysical dimension through the depiction of nature. This was the tradition of Nordic Neo-Romanticism, a considerable influence on the cultural milieu of early 20th-century Poland and Russia. Ciurlionis’ work embraced, crystallized, and interpreted these multiple artistic ideas at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries that also have humanist and cultural importance to the community of the 21st century” (23).

Listen to Ciurlionis’ composition for organ.

See Ciurlionis’ paintings, click here.

Among other cultural institutions established during the first years of independence, was the Lithuanian Theatre, Music, and Film Museum, founded in 1926. Lithuania, like the other two Baltic States Estonia and Latvia, adopted a liberal democratic constitution. However, Lithuania was the first country among her Baltic neighbors where an unruly democracy was soon replaced by autocratic rule. An authoritarian presidential regime was established in 1926, under the leadership of Antanas Smetona, who called himself “the nation’s leader” (24). The authoritarian policy in culture, especially in comparison to the Soviet Union, was relatively non-invasive, and artistic and literary life bloomed. As WWII approached, Lithuania tried to preserve neutrality in its foreign policy, which was especially hard after Germany annexed Klaipeda (the former German territory) in 1939. But Lithuania’s future could not be defined by the government’s policy and careful neutrality, it directly depended on the struggle between the two great powers of the time: Germany and the Soviet Union.

Knowledge Check

- How did Lithuanian overcome the illiteracy of its agrarian population?

- Why was it so important for Ciurlionis to learn the Lithuanian language?

- Why did Lithuania become the first country to establish an autocratic regime among the three Baltic states?

The War Years, 1940-1945

After the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, 20,000 Red Army troops were stationed in Lithuania. In return for Lithuania’s accommodation of the army, the Soviets gave Lithuania back its capital, Vilnius. On May 30, 1940, Moscow published a communique about the kidnapping of two Soviet soldiers in Kaunas and provocative anti-Soviet activities in Lithuania. Molotov demanded the formation of a new government and additional units of the Red Army “to ensure proper enforcement of the pacts” between the countries (25). The formation of the so-called People’s government followed. On June 21, 1940, the new Interior Minister of Lithuania and a communist, wrote that the Red Army would help to maintain Lithuania’s independence. After “free votes” in the presence of the Red Army and support from Moscow, in August 1940 Lithuania became the 13th Republic of the Soviet Union (26). Immediately the massive expropriations of businesses started. Changes in culture and education followed. Many Lithuanian national authors were excluded from the school curricula and teachers were requested to tear out the ideologically “wrong” pages from the textbooks. From 77 pre-war newspapers and magazines, only 33 remained during the Soviet period. Deportations and arrests soon followed. During two days in July, 2,000 Lithuanians were arrested. On average, 200-300 people a month were arrested (27). Lithuanians started an insurrection against the Soviet system during the very first days of the Nazi occupation, with units of the Lithuanian army rebelling against the Red Army commanders. When on the 25th of June, the German Army entered Kaunas, it was greeted as liberators. The Nazis, however, never recognized Lithuanian demands for independence. Despite the resistance of the Lithuanians, about 75,000 were conscripted and sent to forced labor camps in Eastern Prussia. Although the theatres worked, Kaunas’ and Vilnius’ universities were opened in 1941 but closed in 1943. All textbooks, both for elementary and high school education, were censored. In March 1943, together with 47 other Lithuanian intellectuals, a famous Lithuanian writer, playwright, and translator Balys Sruoga (1896–1947) was sent to Stutthof concentration camp, all accused of anti-Nazi propaganda. Based on his experience in the concentration camp, Sruoga later wrote his best-known novel Dievų miškas (The Forest of Gods, published in 1957). In his book, Sruoga described a man’s life in a concentration camp, the beatings or torture, betrayals and generosity, and the will for survival. At the beginning of the 21st century, a Lithuanian film studio produced a movie based on the book.

The Holocaust during WWII in Lithuania is one of the most tragic pages in the country’s history. “The Lithuanians carried out violent riots against the Jews both shortly before and immediately after the arrival of German forces… By the end of August 1941, most Jews in rural Lithuania had been shot… The surviving 40,000 Jews were concentrated in the Vilna, Kovno, Siauliai, and Svencionys ghettos, and in various labor camps in Lithuania… In 1943, the Germans destroyed the Vilna and Svencionys ghettos, and converted the Kovno and Siauliai ghettos into concentration camps. Some 15,000 Lithuanian Jews were deported to labor camps in Latvia and Estonia. About 5,000 Jews were deported to killing centers in German-occupied Poland, where they were murdered. Shortly before withdrawing from Lithuania in the fall of 1944, the Germans deported about 10,000 Jews from Kovno and Siauliai to concentration camps in Germany. Soviet troops reoccupied Lithuania in the summer of 1944. In the previous three years, the Germans had murdered about 90 percent of Lithuanian Jews, one of the highest victim rates in Europe” (28).

Please read the article “Neglecting the Lithuanian Holocaust”.

Knowledge Check

- Please explain how Lithuania became the 13th republic of the Soviet Union.

- Why did the Lithuanians enthusiastically greet the Nazis upon their entering Kaunas?

- Explain why Lithuanians have until now neglected to acknowledge Holocaust atrocities (read article above)

Soviet Occupation

The Soviets reoccupied Lithuania in 1944, marking the start of the longest anti-Soviet partisan war in the Baltic states. The partisan groups that had resisted the Nazis mobilized their forces against the Soviets. In 1948, separate partisan groups formed the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters. In their programs, the partisans explained that their main goal was the creation of independent Lithuania. Approximately 50,000 men and women participated in the fighting against the Soviets until 1953, and 20,000 were killed. The help from the West, that the partisans hoped to receive, never came. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the KGB captured the leader of the Lithuanian fighters, Jonas Zemaitis.

Zemaitis – Arrest and Execution in Moscow

Jonas Zemaitis was arrested in 1953 and sent to Moscow at the demand of Lavrenti Beria, leader of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Beria offered him his freedom if he would cooperate. He refused and was subsequently executed in Butyrka prison in Moscow and buried at the Donskoy Monastery. His last words in the court were: “I, as well as the followers of mine, think that the Soviet Union with the armed forces invaded our country. I consider this behavior of the Soviet Government unauthorized… All underground activities against the Soviet Government, a participant of which I was, I consider right and not illegal. I just want to stress that as much as I commanded to the Lithuanian Movement for Freedom I made every effort to keep to principles of humanism. I didn’t allow any brutal activities. I know what the sentence of the court will be. I still believe that the struggle I have led for nine years will bring its results” (29).

The Thaw in Lithuania

After the death of Stalin and during the Thaw, as in the other two Baltic republics, Lithuanian cultural life blossomed. Vilnius became a center for jazz-style music; the famous future school of Lithuanian photography was established in the late fifties. Folklore festivals were revived. Lithuania became a center for the graphic arts in the Soviet Union. Vilnius also was the first city in the USSR to use Scandinavian city-planning architectural concepts. During the Thaw, the Lithuanian film studio produced two films about postwar partisan experiences, which, although politically correct on the surface, allowed the audience to understand the depth of the defeated movement for independence (No One Wanted to Die, by Vytautas Zalakevicius and Steps to the Sky, by Raimondas Vabalas, both in 1966.) Vilnius in the Thaw era became an inspiration for the great Russian poet Josef Brodsky. Between 1966 and 1972, Brodsky visited Lithuania at least 10 times.

These visits left imprints in Brodsky’s poetry. The first of his poems that introduced the Lithuanian theme is called “In Palanga” and was most likely written in 1967. Later Brodsky wrote a poem cycle called “Lithuanian Divertissement” (1971), which he dedicated to Tomas Venclova, and a mini-poem entitled “Lithuanian Nocturne” (1974-1983). An unfinished poem was written in 1970, “Autumn happened to be warm, I lived in Lithuania…” (30). For the Russian and Jewish artistic intelligentsia, summer vacations in the Lithuanian seaside resorts, Palanga and Klaipeda, could be compared only to a short exposure to European life. The proximity to Poland and the numerous connections of Lithuanians and Jews with their relatives abroad, made trips to Lithuania liberating and eye-opening, especially from the heavily censored and infiltrated-by-the-KGB Moscow and Leningrad (St. Petersburg). It was during the Thaw, that a poet Tomas Venclova became a prominent figure in the Lithuanian literary world. Tomas Venclova (born in 1937) was a friend of the poets Josef Brodsky, Anna Akhmatova, and Boris Pasternak, whose poems he translated from Russian into Lithuanian. Venclova was born in Klaipėda, a graduate of the University of Vilnius. Venclova was one of the five founding members of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group, which was a part of the Lithuanian and Russian dissident movements. As he was forbidden to publish his own works (except for samizdat, which was a publishing system within the Soviet Union, by which forbidden literature was reproduced and circulated privately), he translated Baudelaire, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, Robert Frost, and Osip Mandelstam. In 1977, he was forced to immigrate. Since 1980 he has taught Russian and Polish literature at Yale University.

Please read “The Sign of Speech: Conversation with Tomas Venclova“.

Knowledge Check

- Please describe how the Lithuanian partisans continued their war against the Soviets after the end of WWII and the reoccupation of Lithuania.

- Please explain why Lithuania was considered “the zone of comparative freedom” for people from Moscow and Leningrad.

- Please explain how Josef Brodsky and Tomas Venclova became friends.

Last Decades in Soviet Union

In the 80s, when the Soviet Union entered the stage of stagnation, the potential changes in Lithuania and other Baltic republics became more obvious than elsewhere in the Soviet Union. The death of Brezhnev in 1982 underlined the age of the party officials. In Lithuania, many of the “old guard” were about to retire. The growing access to telecommunications and media was changing the expectations of the young. Although still rare, videotapes became available on the black market. In 1984, four Lithuanians were sentenced to two years in prison for showing for profit a videotaped pornographic film (31). Although the general mood of Lithuanians was somber, the eighties were the peak for Lithuanian theatre directing, producing among others, the genius of Eimuntas Nekrosius (1952-2018). Born in a Lithuanian village, he received his degree in directing from the Moscow State Theatre Institute in 1978. Upon returning to Vilnius, he worked in the Lithuanian State Youth Theatre. His production of The Square (1980) told the story of the broken lives of Lithuanian deportees, who were returning home after years of hard labor in Siberia. In 1982, he directed a rock opera based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. He gained international attention with his production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, which, after touring Europe, was played in New York in 1986. During the decades since that time, Nekrosius’ reputation has continued to grow in Europe. His innovative productions based on the plays by Chekhov, Pushkin, and Shakespeare have been honored with major international theatre prizes in France, Germany, and Italy. Marvin Carlson, a renowned American theatre critic, and theorist wrote about his Hamlet:

“Water, ice… continually recur in differing forms and combinations. Seemingly central to the court life and its ceremonials are huge crystal goblets filled with water, used of course for the many scenes of drinking, but also as formal parts of certain settings and as receptacles in which letters and other objects are often placed after use (and in which they invariably dissolve). Like the blade, the ice, water, and dissolving cluster of images are associated closely with the ghost. When he first encounters Hamlet, he appears in a huge white fur coat carrying a block of ice. As he instructs Hamlet he slowly removes Hamlet’s shoes and stockings, rubs his bare arms and chest with water from the melting ice, and, when asking him to swear, presses first Hamlet’s hands and then his feet determinedly down onto the block of ice. After the ghost leaves, Hamlet raises the block above his head and smashes it to the floor. He then scrambles among the broken pieces and holds aloft a gleaming object- a knife that had been frozen, embedded in the block.

After the play scene, the ghost carries in a strange object, a chandelier composed of hanging blocks of ice and candles, which he fastens to the bottom of the circular blade. Soon after, Hamlet enters, wearing a white shirt given him by the ghost. He removes his shoes and stands in the pool of water created by the slowly dissolving chandelier to deliver the “To be or not to be” speech. As he speaks his shirt, actually made of light paper, slowly dissolves as melting drops from the chandelier continue to fall on him. In the end, he collapses and while Gertrude and Horatio drag him to safety…” (32).

In Eimuntas Nekrosius’ creativity, the pagan images of fire and water were combined with contemporary European theatre technique. His art absorbed themes, melodies, and images of Lithuanian culture from the ancient past to the present day. Eimuntas Nekrosius died suddenly in 2018. An exhibition, dedicated to his life and art, is mounted in the Lithuanian Theatre and Film Museum in Vilnius.

Although always suspecting the Baltic people of hidden anti-Sovietism, the Soviet authorities nevertheless used beautiful Baltic settings for various international gatherings. For example, in Vilnius in 1985, U.S. and Soviet writers met for a colloquium. Other international guests came to the republic regularly. Ironically, on the one hand, always observing collaborations with foreigners with casual suspicion, the Soviets themselves, unintentionally, encouraged it. Gorbachev’s policy of Glasnost and Perestroika was the opening of a Pandora’s box. In February 1988, spontaneous demonstrations started in Vilnius and Kaunas that were celebrating 70 years since the Lithuanian Declaration of Independence in 1918. In June 1988, the Lithuanian Reconstruction Movement (Sajudis) was formed, and the congress of Sajudis took place on October 22-23, 1988. All three Baltic republics’ movements for independence were well-coordinated with one another. The first mass rally of Sajudis happened in June 1988 and gathered 50,000 people in Vilnius. Sajudis’ next rally doubled the number of participants. 250,000 people came to remember the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed in August 1939. The cathedral of Vilnius was returned to the Roman Catholic Church. On May 18, 1989, a declaration of sovereignty was adopted by the Supreme Soviet of Lithuania. In early August a long human chain stretched from Tallinn to Vilnius. At the beginning of 1990, the elections to the Supreme Soviet were the first multi-party elections held in the USSR. On March 11, the newly elected Supreme Soviet proclaimed the restoration of the Republic of Lithuania with its pre-war code of arms and flag (33).

We hope you have learned a lot about Baltic history and culture, the Baltic peoples’ fight for their independence and preservation of their national identity, and the strength they obtained from their cultures and traditions. Being passed from one powerful neighbor onto the other, be it Sweden or the Kingdom of Poland in medieval times, or Imperial Russia, or Nazi Germany in the modern era, or the Soviet Union in the 20th century, all three states preserved their cultures, languages, and national identities, building their independent future in the 21st century as members of the European Union and supported by their alliance with NATO.