Choreographer Danielle Agami likes algebra’s complicated puzzles, the ones that require subcutaneous investigation to approach their solutions. Her movement class also fosters this kind of inquiry. On March 25, 2021, she Zoomed into The Ohio State University Department of Dance for a master class with participants in Audiences and Online Reception: Before and After Covid. She guided us to negotiate various interlocking qualities in our bodies to find a summary balance. She directed us to engage our spines like seaweed and our heads like helium-filled balloons (and then to re-locate that helium in our pelvises). We led our bodies by the elbows; we pushed one palm against the other with the full force of each arm, then did the same with the legs against the floor; and we retained a rumbling quake deep within our full-body investigations.

The movement exploration in Agami’s class is a kind of compositional practice, wherein participants compose the body. Her visceral, gastronomical imagery renders seaweed limbs and interstitial ribcage cartilage melting like butter. Negotiating these divergent movement qualities established spaces between my muscle fibers that made way for ascertaining renewed bodily information. As participants, we toggled between Agami’s verbal instructions and watching her and each other on our individual screens to tap into feelings of dancing together across the online distance.

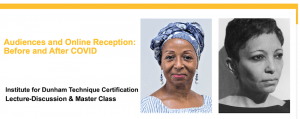

Agami founded her Ate9 Dance Company in Seattle, Washington in 2012 and moved it to Los Angeles in 2013, where she is currently based. She began her dance career with eight years in the Batsheva Dance Company in Tel Aviv, as a dancer and rehearsal director, then moved to New York in 2010 to serve as Senior Manager of Gaga USA. She left New York for Seattle and Gaga for her own explorations to carve her way as an artist and to establish a touring company in the United States. Her company has toured widely, stopped only by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The main change that Agami identifies in the pandemic is not to take anything for granted. And, she told us, she believes the pandemic has made people in the wider society understand the precarity that artists have long experienced. But for her, the pandemic has not been about dancing. She has made some short films to keep creating, but she was under no pretense that dancing on Zoom was any kind of replacement for dancing in the theater. Her audiences? They disappeared. She took another job and considered preparing for medical school to fulfill a long-held dream, but decided instead to continue her dance research and to establish the arts more prominently in society. Zoom has been necessary during the pandemic, but she has not given up her desire to perform in large theaters for the immediacy and power of live performance. She plans for Ate9 to tour extensively as the pandemic wanes. As we transition out of the pandemic’s peak, she looks forward to seeing more young artists take up the political charge with provocative experimentation to challenge conservative societal structures.