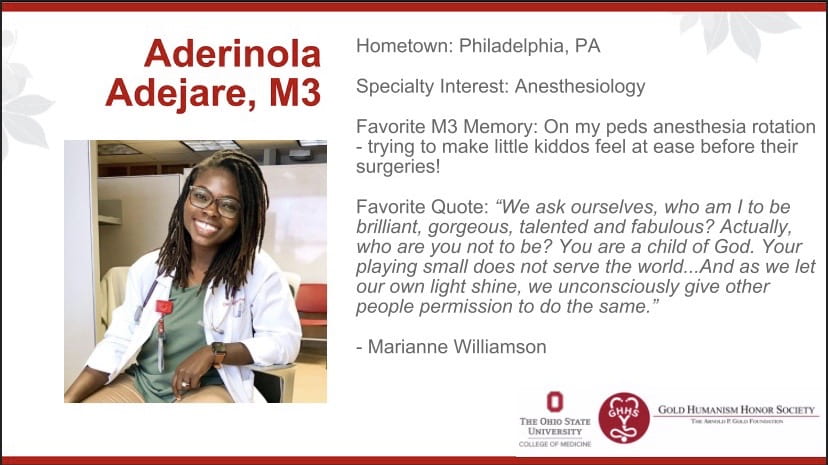

During third year, I attended a Minority Women in Medicine roundtable here at OSU and left feeling inspired, charged up, and ready to take on any challenge that comes my way as black women in medicine. What I appreciated most about this event was being able to hear from successful women in medicine and in this intimate setting, ask them how they did it – How they got to where they are, how they are able to balance motherhood and medicine, balance marriage and medicine, navigate race in the work place, gender and more. No questions were off limits. In this setting, I was able to hear some of the challenges one of my role models experienced over the years. She is black woman, the program director of her department, practicing in a specialty I plan on going into. She is also a mother and a wife. She is what I’ld like to call “Black girl magic.” She carries herself with an incredible poise and confidence that I aspire to emulate. However, as much as I’ld like to put her on a pedestal, highlight her various accolades, and praise how approachable she is as an individual, I would be remiss if I did not also highlight that she like I and every other person, has also encountered challenges over the years. These challenges were present in medicine, in motherhood, and other facets of her life. It was a reminder to me that no one’s life is in fact perfect. What matters however, is how you respond to the challenges you encounter. Resilience is absolutely key, so is staying optimistic and having a positive outlook.

Currently, reportedly only 2% of all physicians are black women (see TIME article here). This under-representation, I do believe affects healthcare delivery and outcomes, considering a much larger portion of our patient population are black, and research as shown patient outcomes are better when treated by a physician who looks like them. Although this statistic is shocking, I remain optimistic. One, because of OSU’s relatively larger acceptance of a underrepresented minorities into medical school, thereby making a huge contribution to diversifying medicine; two because of my work with SNMA, an national student organizations which also works to diversify medicine; three because of my work with my community health education project, helping to educate an underserved population about metabolic syndrome; and four, because I know I will make an impact no matter where I go for residency and where I go to practice as an Attending. My goal is to remain resilient, encourage other minorities to pursue medicine, serve as mentors for others, and continue to change and challenge the healthcare system from the inside out.