The ongoing political and military conflict in Eastern Ukraine is the backdrop for research by Ph.D. candidate and sociolinguist Yuliia Aloshycheva. Ukraine has a symbolic East-West divide that plays out not only in political terms, but also in linguistic ones – Russian is symbolically assigned to the ‘East’ and Ukrainian to the ‘West’ (or to the nation as a whole). However, beyond broad stereotypes, there is little understanding of the internal dynamics of the language-place relationship. How do Ukrainian citizens ‘imagine’ the country and its languages?

The ongoing political and military conflict in Eastern Ukraine is the backdrop for research by Ph.D. candidate and sociolinguist Yuliia Aloshycheva. Ukraine has a symbolic East-West divide that plays out not only in political terms, but also in linguistic ones – Russian is symbolically assigned to the ‘East’ and Ukrainian to the ‘West’ (or to the nation as a whole). However, beyond broad stereotypes, there is little understanding of the internal dynamics of the language-place relationship. How do Ukrainian citizens ‘imagine’ the country and its languages?

In her dissertation, Yuliia is developing an emic understanding of place in Ukraine and how sociopolitically charged language varieties are connected to people’s conceptualization of place. She is looking at how people’s self-orientation (for instance, toward the nation as a whole vs. towards their immediate locale) influences how place, language and social characteristics get linked together at this sociopolitically important moment. Do Eastern and Western Ukrainians have the same understanding of the sociolinguistic space of Ukraine? Is the way that people link place, language and social characteristics different than before the current conflict?

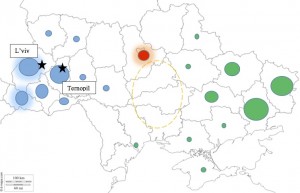

Part of Yuliia’s data comes from Skype interviews, the goals of which were to elicit participants’ explicit intuitions about how language ‘works’ in Ukraine, their attitudes towards language varieties, and how they orient themselves to sociolinguistic positions. The interviews were conducted with participants from three geographically distinct regions of Ukraine in October-November 2015. Yuliia reflects on her experience of conducting the interviews:

“Having dealt with human subjects only indirectly, through online questionnaires, the idea of conducting 45 one-on-one interviews seemed terrifying at first. What if no one signs up? Should I be paying my participants more/less? How do I make them talk? The list of questions just kept growing bigger and bigger. My task as an interviewer seemed to be further complicated by the uneasy sociopolitical situation in the east of Ukraine: How do I go about asking sensitive questions? How do I reconcile the multitude of identities that I am ‘made of’ and which identity do I put forward in order to build rapport with the participants?

Even though looking back now, I understand that many of my fears were ungrounded, I would like to share a few things that I learned in the course of interviews. One is being attentive to your interviewee, showing genuine interest in their personality, in what they say. Being a discoverer, a learner, rather than a teacher, an authority, is key. Another important thing is flexibility . I remember one moment I could be perceived as an empathetic ‘I’m-just-like-you’ co-Ukrainian and in the next moment I was an estranged scholar from an overseas university.

. I remember one moment I could be perceived as an empathetic ‘I’m-just-like-you’ co-Ukrainian and in the next moment I was an estranged scholar from an overseas university.

All in all, I think it was a fantastic experience that helped me grow a lot as a sociolinguist but also as an interlocutor.”

Yuliia is currently analyzing the interview data, looking at perception of linguistic variables like akan’e (vowel reduction in unstressed syllables) vs. okan’e (non-reduction) and pronunciation of ‘what’ as [ʃt͡ʃo] vs. [ʃo]. The interviews produced rich, multifaceted data, so we can’t wait to see the results! (Coming soon!) The dissertation work is being co-supervised by Andrea Sims (Slavic) and Kathryn Campbell-Kibler (Linguistics).