By Edited by Xiaomei Chen

Reviewed by John Yu Zou

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright February 2004)

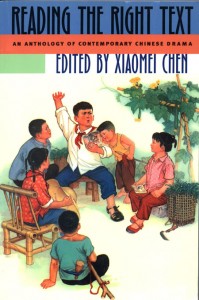

Xiaomei Chen, ed. Reading the Right Text: An Anthology of Contemporary Chinese Drama. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003. 464 pp. US $65.00, ISBN:

0-8248-2505-5 (cloth); US $29.95, ISBN: 0-8248-2689-2.

The title of this book may suggest to readers that it is a companion volume to the editor’s earlier research monograph, Acting the Right Part: Political Theater and Popular Drama in Contemporary China (Hawai’i, 2002). But browsing through the book will indicate that this is a companion volume only in a very particular sense. Unlike the monograph, which covers Chinese theater of the Maoist era, this anthology consists of plays written and published in the post-Mao years. The connection between the volumes, then, seems to be an ironical if not polemic one: if with Maoist politics there is always the “right” part to play, now in post-Mao China, is there still a “right” text to read? For western students of modern Chinese drama, these selected works are a welcome addition to the extant corpus in English translation. Apart from earlier issuances of singular plays by the Commercial Press in Shanghai and the Beijing Foreign Languages Press, such as Cao Yu’s Sunrise (H. Yonge, trans.,1940) and Thunderstorm(Wang Tso-Liang and A.C. Barnes, trans., 1958), and Lao She’s Teahouse (John Howard-Gibbon, trans., 1980), there have been three recent collections of modern Chinese plays published in English. They areTwentieth Century Chinese Drama: An Anthology (edited by Edward M. Gunn, Indiana University Press, 1983), An Oxford Anthology of Contemporary Chinese Drama (edited by Martha P. Y. Cheung and Jane C. C. Lai, Oxford University Press, 1997) and Theater and Society: An Anthology of Contemporary Chinese Drama (edited by Haiping Yan, M. E. Sharpe, 1998). Perhaps because of this fairly broad previous coverage of a relatively limited corpus, particularly with respect to the recent period, Reading the Right Text presents a cluster of dramatic works, many outside the received canon, and of varying reputation and caliber. The disadvantage of this approach is, of course, that in turning its pages, the reader may occasionally encounter what Peter Brooks, speaking of the theater of the French Revolution, glosses as “pretty silly stuff.” Fans and scholars of Chinese spoken drama may question the absence of the more performance-centered or socially provocative works by figures such as Meng Jinghui or Zhang Guangtian. The merit of this approach, on the other hand, may lie in the fact that the unevenness of quality and style draws attention to the creative crisis and experimental spirit in a genre and—speaking of that post-1949 China—a social institution that has been through tough times since the 1970s, with diminishing government backing and the merciless onslaught of commercialism. The introduction to the volume furnishes useful historical and discursive information to prepare students at the undergraduate level for the plays themselves. The translations are very well done throughout and, in some cases, even make the dialogue read more sophisticatedly than in the original. In what follows, I will introduce and comment upon each of the six plays in the volume.

No matter what experience you have with modern Chinese drama, the first play in the collection, The Dead Visiting the Living (1985), may strike you as an oddity. A random incident of fatal violence on a city bus sends the victim, now a ghost, on a quest among his one-time fellow passengers to understand their inability to intervene on his behalf and stand up for justice. Though the question about the value of an ordinary person’s life sidesteps the Maoist mandate for “heroic” celebrations, and there are elements of formal interest—for example, the responsive drumbeats, choreographed lighting, a fluid chorus—the play exudes an awkwardness that constantly reminds one of a theater only recently released from the Propaganda Department’s firm hand of formal and ideological guidance. Even if one takes the brawl over a stolen wallet on the bus as an indicator of the play’s anti-edifying interest, there are times when this interest is pursued to an unnecessary extent. The ghost and his living woman friend, for instance, are given diminutive and giant panda-esque names as Xiaoxiao and Tiantian. The ghost has “tears welling up in his eyes” throughout the play, since he is repeatedly moved by the lives of ordinary human beings with whom he once shared a bus. The woman, a tailor and peddler of clothes by profession, flits to and fro with a guitar strapped to her shoulder, humming senseless baby-talk lyrics such as “I am a happy fledgling. On spring’s keyboard I jump and sing.” But it is when Xiaoxiao, the dead man, sails onto the stage in his “winged snow cape” to alleviate a little girl’s guilt-ridden conscience that you really want to pinch yourself to remember that all this is not meant to be a joke.

This being said, however, such a generally quite painful theatrical product is not without significance as a social text. The formal undoing of Maoist “realistic” theater, the rash execution of which explains the play’s many failures, is mediated by acute historical references to the undoing of the orthodox Maoist social and political fabric in contemporary China. As one passenger states almost off-handedly in a conversation about Xiaoxiao’s random death, “nowadays nobody’s afraid of anybody.” When dissuading Tiantian from gathering money to erect a statue for him, Xiaoxiao quips that she needs only to burn paper money and that “these days people even burn paper cars, paper villas, and paper refrigerators for their departed.” And those who have seen the recent Chinese movie Crying Woman may realize that such imaginary extravagance is borne out with ample comedy at Chinese funerals these days, when paper mistresses, paper space shuttles, and even paper Titanics are on offer. Most importantly, the play’s tribute to the “heroism” of an ordinary, non-heroic man also represents an attempt to come to terms with an extraordinary, revolutionary mode of life that has passed by. At one especially effective moment in the play, a memorial procession is staged for Xiaoxiao, now politically recognized as revolutionary martyr. A gigantic empty picture frame is erected amidst the crowd, while Xiaoxiao the ghost often “departs from the frame and the procession, but is again and again shoved back in his place.”

The second play, The World’s Top Restaurant (1988), by contrast, draws its stylistic resources from a somewhat conservative pool of “realistic” precedents. An unabashed reiteration of Lao She’s masterpiece, Teahouse, the play narrates the gradual rise and sudden fall of a duck restaurant in Beijing at three important historical moments: the beginning of the warlord regime in 1917, the height of its influence in 1920, and its anticlimactic end with the Nationalist triumph of 1928. Like Teahouse, The World’s Top Restaurant is imbued with political allegories, narrative anxiety, and a great deal of (constructed) folklore. Given that such established ingredients for theatrical realism have long been a part of spoken drama in post-1949 China, the play acquires structural solidity and performative definition even as a mere written text. The three-act play tells of the initial interview, the early efforts, and then the great success and unexpected destruction of Lu Mengshi, a man of humble origin but great dedication and intelligence, as manager of one of Beijing’s more prestigious eateries. The trajectory of his rise and fall coincides neatly with the beginning and termination of the so-called warlord regime, often taken to be an era of great chaos and fragmentation. The play’s implicitly positive, and therefore revisionist, assessment of the regime—insofar as the restaurant consolidates its foundation for real growth at the height of the regime—seems to bespeak a preference for the lessening of state presence for the benefit of social growth, a rather familiar doctrine among reform-minded intellectuals of the 1980s. Lu, the overachieving new manager, and his menacing adversaries (i.e., the hereditary owners of the restaurant) predictably rehearse the popular imagination of Chinese high politics of the time. Should the restaurant be likened to the Chinese state, manager and owner then point to technocratic reformers and conservative beneficiaries of the earlier state-founding revolution. The manager’s unexpected dismissal from the restaurant and seizure by the police because of the owners’ intrigues then indicate a rather somber apprehension of the drastic and imminent backlash that the reforms may bring upon itself.

Perhaps to counterbalance such implications within the contemporary representation of Chinese politics, the play also carefully orchestrates its own appeal as mainstream entertainment. The wealth of well-articulated details of a by-gone Beijing, given their absence in the modern metropolis, apparently functions not only in an open and critical allegorical context, but also to construct a fantasy world that is quite enclosed within itself. The citational and fabricated nature of purchase and preparation, roasting and serving rituals, and the entire political economy—i.e., the exploitation, commerce, and fetishization—of the duck as a food item, all seem to afford the modern Chinese theater patron a fictive sense of historical grounding and a consumer’s appetite for the “pre-modern” way of life. To some extent, the restaurant even duplicates the theater as an imaginary locus of social interaction where members of varying strata and communities rub shoulders. But also as with the theater, the symbolic evocations and performative routines of the restaurant constitute a means of disengagement from “realities” of ordinary city life.

Black Stones (1988), which appears next in the anthology, impresses me as an interesting transformation of the Maoist propaganda play. The point of the work seems to be two-fold: first, to give expression to substantial social grievance, and second, to resolve that unhappiness within a performatively adjusted but ideologically reinforced political system. To describe works of post-Mao theater in terms of Maoist political “therapy” is, of course, overly simple. What really merits interest is a unique theatrical configuration in which the somewhat obsolete Maoist format is transfigured to address the post-Mao social imagination. The play begins with tensions within a petroleum exploration team in China’s northeast that threaten to lead to the unit’s disintegration. The captain fails to command attention; a senior member wants to resign so as to reunite with his wife; a junior member generates bad blood among colleagues with endless complaints; and the most capable and resourceful member is not only a bully but also becomes embroiled in an adulterous affair with a local woman. At the play’s end, however, we are provided with social as well as emotional catharsis. The captain conveniently dies on a heroic mission; the senior member is repentant and decides to stay on, his wife joining him at work; the delinquent junior member is also reformed when, finally, he is able to quit; and the capable member is exonerated for his misdeeds, for the woman is now revealed to be battered by her husband’s family. Unlike The Dead Visiting the Living, which awkwardly dwells on social crisis and its own formal possibilities, Black Stone directs its expert attention toward the repair of social tissues under stress. Between the Hegelian moments of antithetical conflict within the team, and synthetic triumph when the group is again brought together under the auspices of a state mission, there are two characters whose constancy in the play gives them particular prominence: the rational and independent technician and the perspicacious and open-minded party secretary. Even though the radical sublimation within the group cannot be solely attributed to their actions and leadership, their unchanging dedication to the mission and unerring ability to manage crises position them at the center of a renewed social and political cohesion.

Though the play is quite well written and structured for a “social management” piece, the transfigured political momentum in post-Mao China obviously besets it with more problems than its tried-and-true conventions can accommodate. The net result is more than a few goose- bump inducing moments, such as those the reader may have experienced with The Dead Visiting the Living. Industrial workers who are able to recite from Tagore and discuss philosophy may have made sense in a Maoist context of a tyrannical merger of the working and educated classes, but in the reform era, when political mobilization in the name of reform effects a widening of these very social gaps, this sort of literary and philosophical dialogue seems dishearteningly nonsensical. Furthermore, the celebration of “familiar” human conditions sometimes borders on the preposterous. To show psychological depth, a bullied roughneck is portrayed as doting with melodramatic tears on a wounded baby goose. And to indicate male mischief, the play belabors a rather hackneyed if not childish motif of one man peeing into another’s drink — a motif that the reader has already seen in The Dead Visiting the Living, and that also appears in Zhang Yimou’s famous movie, Red Sorghum.

Jiang Qing and Her Husbands (1991) may be the most deliberate and calculated work of formal innovation in the entire anthology. The play capitalizes on the intersection between politics and theater in the life of Jiang Qing, Chairman Mao’s long-time wife and convicted villain of the Cultural Revolution, and thus is not only experimental, but also sensationally exploitative in general appeal. With considerable stylistic savvy, the play employs the stage as a fully citational structure, in that the performance begins and ends with the post-Mao political denunciation of Jiang Qing, and lapses subsequently into a variety of scenes of her earlier dramatic incarnations: as Ibsen’s Nora on Chinese stage, as a radical city girl at Mao’s revolutionary base in Yan’an, and finally as a formidable political figure during the Cultural Revolution. In the meantime, her increasing political leverage is poignantly balanced by her decreasing feminist edge. As a left-leaning actress, the youthful Jiang lives a life that defies social convention and mores. In the Yan’an episode, it is her political naiveté and bold personal style that captures the attention of Mao. Her full assimilation into state politics during the Cultural Revolution, however, turns her into Mao’s mindless loudspeaker. The irony seems to be that, as a feminist, Jiang Qing is always driven by a strong self-centered will, be it in the rejection of Tang Na, her one-time lover, or in the approach to Mao, the political leader, but it is also the ferocity of her pursuit of power that ultimately results in her corruption and political destruction. Instead of simply demonizing her, the play underlines via the communist leader’ domestic life a unique contest between a feminist and Maoist state that purports to be the guardian patron of women’s liberation. To the extent that it carries an articulate political challenge beyond the formal transgression of Maoist theatrical “realism,” Jiang Qing and Her Husbands may indeed be taken as the post-Mao Chinese experimental theater with a vengeance. But it is exactly at moments where such revisionist theatrical agenda is expressed with most intensity that the play also defaults to misogynist interest. The weaving of a semi-biographical account of Jiang’s theatrical and revolutionary adventures with vast societal and political changes in modern Chinese history is both provocative and pleasing to the extent that history is not only individualized but also eroticized. But more importantly, the dramatization of Jiang’s destruction as a feminist takes on aspects of what Rene Girard describes as “persecution.” The sadist vision of a humiliated political figure, especially at the beginning and the end of the play, celebrates with sinister pleasure the fall of a woman overstepping her bounds. In the end, the play’s protest is not only directed at the Maoist state, but also, if not more vehemently, to a politicized, and therefore corrupt and grotesque, woman on death row.

In Green Barracks (1992), the fifth play, we witness a specimen of recent Chinese theater whose silliness sometimes rivals that of The Dead Visiting the Living. The play is about a group of young women who overcome their initial discomfort with military lifestyle to become qualified soldiers. Published a good seven years after the The Dead, Green Barracks still features characters with cuddly diminutive names such as Diandian and Xiangxiang. And although the story is endowed with a military backdrop, at one point the reader may find the women soldiers engaged in preposterously idyllic pastimes such as “catching butterflies,” and “kissing the doll.” But in the main, it is again a “social management” fantasy. As in Black Stone, the younger generation (i.e., the soldiers) initially has its share of discontent: drills are harsh; the dress code draconian; love affairs forbidden; and their Spartan barracks are in the midst of Shenzhen, a reform-era boom town. Unit leaders from the older generation, however, win them over by sacrifice and edifying example. The captain dies in Black Stone, and in this play, it’s the company commander’s son who passes away. What makes the text interesting is its correlation with the rise of light entertainment in urban China in the 1990s. Despite its representation of women as a performative category, the play seems to harbor less interest in advancing a feminist cause of the critical or the state-sanctioned kind than in showcasing the bodily presence of youthful women as an urban spectacle for mass consumption. Though still framed within the orthodox performance structure of political sublimation, Green Barracks obviously invests considerable effort in the parading of feminine details from these women’s lives: their mannerisms, fashion preferences, and romantic inclinations apparently transgress the social mandate of such plays, which is the settlement of grievances and the promotion of post-Mao political transformation. In the historical context of twentieth-century Chinese popular culture, such a theater of a sensual appeal and misleading political neutrality may indeed recall the “soft cinema” the communist and leftist intellects used to relentlessly slam in the 1930s under the Nationalist regime. In post-1989 urban society, the irony is that plays like these appropriate established Maoist forms for the purpose of entertainment.

For me, the play that best captures the social vision and creative efforts of recent Chinese theater is the anthology’s concluding piece, Wild Grass (1989). In terms of storyline, this lesser known work is similar to The World’s Top Restaurant and Jiang Qing and her Husbands in that it devotes considerable theatrical flair to the rather conventional business of tracing a powerful character’s rise and fall. The nice thing, however, is that it situates this Balzacian tale of male self-aggrandizement and self-destruction within the mighty flood of peasant workers migrating into China’s booming cities. The narrative goes something like this: A country boy by the name of Fourth has made it as a builder in the city by dint of his will for success and knack for doing the right thing (including turning down his teenage sweetheart for a crippled woman with a well-placed uncle), only to be framed by his business partners and reduced to a jail bird. Though the plot, especially in summary, may seem somewhat trite, the play’s abundance of historical details and charged emotions give it a unique robustness and originality. A displaced man in the city, which does not recognize him as its own, Fourth endeavors to turn adverse circumstance to his advantage by supplying the city with what it lacks: manpower, not only in the form of the impoverished villagers he brings from his hometown, but also in his own right—as conjugal material for the city’s ineligible unmarrieds. The peasant turns the city into an exciting and oppressive rite of passage. The latter is no mere source of livelihood but an experience of recognition and, maybe more importantly, self-recognition. Making it in the city then transforms the peasant boy into not just an unhappy resident in the city, but an embodied process by which the post-Mao Chinese city is made. He is now the exploited and grotesque medium upon whose sinews and sadness urbanization takes place. He is the becoming of the city. Of course, given its date of publication, the play indeed may also be read as a rather early reference, at another level, to China’s growing and helpless participation in the cosmopolitan circuits of global capitalism.

Because of this overall allegorical resonance, the romantic and erotic affairs between city and country may also be read as bearing upon Fourth’s connections with past and future, tradition and modern life. Erqin, the sweetheart, with her tears, suffering, perseverance, and dignity, always beckons him toward the past, not of the poverty and cruelty of village life, but of morality, innocence, and nostalgia. The cripple who never once appears on stage, however, points to the city’s deformities as well as its attractions. The street hawker, who pushes eye glasses for a living and carries on an affair with Fourth, represents a compromise between the two: a country woman brought down by the city’s demands and temptations. Self-centered and scheming, she is the spitting image of Fourth cast as a female. Such a typology of female characters has existed in modern Chinese literature and theater for a long time; this is merely a citation, recontextualized in a new historical moment. The redeeming quality that helps render these borrowings refreshing and sometimes even compelling is the excellence of the dialogue. For instance, when the street vendor begins to tease Fourth, the following exchange takes place:

Saleswoman: Hey, Foreman, when you’ve got an old friend who’s hurried here from afar, wouldn’t you even give a drink of water to soothe her throat?

Fourth: Would a drink of water satisfy you?

Saleswoman: Then could you buy me some ice cream?

Fourth: I’ve got a bottle of soda in my desk.

Somewhat frivolous and reminiscent of a sit-com? Yes. But between water and ice cream, bottled soda proffered as a compromise bespeaks the straitened circumstances urbanizing Chinese peasants, beset by desire and necessity, must navigate.

John Yu Zou

Bates College