Source: China Daily (3/26/16)

Bookshops: Talk of demise is exaggerated

By Yang Yang (China Daily)

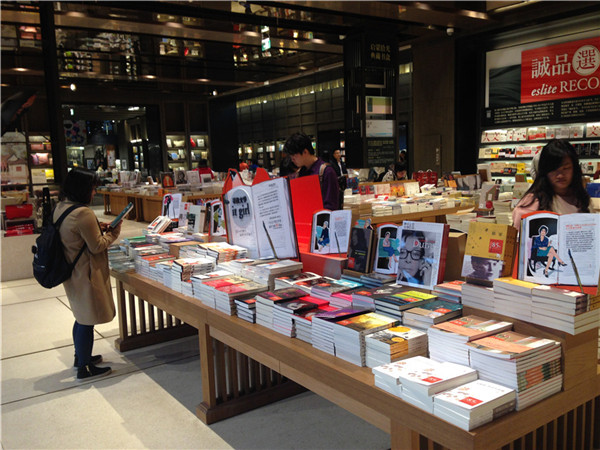

Books by women on display at Eslite in Suzhou Industrial Park. [Photo by Yang Yang/China Daily]

I have just made myself comfortable at a table in a cafe in People’s Square in Shanghai on a recent warm Saturday evening when Hua Chun, 27, started griping about how superficial the world is.

Earlier she had taken a stroll along Huaihai Middle Road with a girlfriend. But no sooner had they entered the huge Muji bookstore, said to be the largest bookshop in the Chinese mainland, they were hightailing it out of there.

“It was too crowded, and I didn’t see many books in there, just a few scattered among clothing and other products, so we headed back to Shanghai-Hong Kong Sanlian Bookstore,” Hua says.

When they arrived at that shop four minutes later it was almost deserted.

“What a contrast,” Hua says, adding that “these days, most young people are keen on seeking pleasure in food, drinks and other entertainment rather than reading books”.

Hua is a serious reader, a lover of classic English fiction and of bookstores. That day she bought two books from Sanlian, Women in White and Selected Short Stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Tracy Zheng, 32, of Nanjing, buys all her books online. She is studying for a doctorate in English language and literature at Nanjing University. When we meet at Librairie Avant-Garde, a 15-minute walk from the university, she says that in the month since the Spring Festival she has talked to no more than five people in the flesh and has not been into a bookshop for about seven years.

The Librairie Avant-Garde in Nanjing, Jiangsu province [Photo/China Daily]

It was a freezing day in early March and it was raining, perfect for staying indoors and finding warmth in a cup of hot tea.

If all the traditional physical bookstores closed, it would probably come as no shock to most. In fact, since 2010, offline bookstores in China have gone through extremely tough times, a great many closing due to the impact of e-commerce, rising costs and plummeting patronage.

The nadir came when sales in physical bookshops around China fell two years in a row, 2012 and 2013, says the industry monitor Open Book.

However, in line with the Taoist saying that once a certain limit is reached, a change in the opposite direction is inevitable, in the past two years there has been a revival in private physical bookstores. Even as the government has urged people to read more, these shops have changed the way they operate to meet the expectations of buyers and are beginning to prosper once again.

Last year, nearly 10 bookstores, big and small, opened in Shanghai, including chain bookstores such as Sisyphus, Yan Ji You, and Muji Books, and smaller individual bookstores such as Mephisto and Rhino Library.

In other cities, big chain bookstores are also shooting up like mushrooms after rain.

In Suzhou, Jiangsu province, the Taiwan chain bookstore Eslite opened its first bookstore.

Inside the Eslite bookstore in Suzhou. [Photo by Yang Yang/ China Daily]

Librairie Avant-Garde in Nanjing, which Western media has called the most beautiful bookstore in China, has opened 11 stores since 1996. Last year it opened a philanthropic library in a place of residence for the She ethnic group in Tonglu county, Zhejiang province. It will open another two bookstores this year.

The local bookstore brand in Shanghai Zhongshuge opened its first bookshop in Songjiang district in 2013. By the end of this year it will have three stores in Shanghai. A branch in Chengdu, Sichuan province, is also on the drawing board.

Tao Shuting, 27, has worked for Zhongshuge Bookstore in Songjiang for three years and has risen through the ranks to become general manager. She loves Chinese literature, she says, and is convinced that physical bookstores will not die.

“Just as a person needs to read good books for his or her soul, a city needs good bookstores for its soul.”

Although Zhongshuge says it has lost money in the three years since it opened, “we are very likely to make a profit this year”, Tao says.

Colin Lang from Taiwan working in Suzhou has been busy since Eslite in Suzhou Industrial Park opened. He is the operations director of the bookstore in the park. Eslite opened in Taiwan 27 years ago and has run at a loss for the past 15 years, according to media reports.

In the three months since its shop in the park opened, business has been good, says Lang.

For him, the closure of offline bookstores provides a good opportunity to reflect on the reasons.

The Librairie Avant-Garde in Nanjing, Jiangsu province. [Photo/ China Daily]

Other coffees available in the cafe include Bonjour Tristesse, Tender is the night, On the Road and Trainspotting, all named after novels.

“The question is whether the old ways can meet consumers’ expectations anymore,” says Lang.

At Librairie Avant-Garde in Nanjing, I order a latte as I wait for Zhang Xing, the operations director, in the cafe. He has worked there for 10 years, half of the bookstore’s life, including in 2008, when the founder, Qian Xiaohua, decided to start producing culturally creative products as he tried to withstand the onslaught of e-commerce.

“The time for traditional bookstores has gone forever,” says Zhang. “They sell books only, but the new fashion is to diversify. Bookstores are going through a transformation, and each newly opened bookstore has its own characteristics.”

He agrees with Lang that “in a new era readers have new expectations for bookstores”.

“Now readers pay more attention to what happens in the space, because they come here not only to buy books, but to communicate with friends, for the exhibitions, to attend a lecture or to learn a skill, which means that bookstores will become a comprehensive cultural space. Eventually all bookstores will be like this, otherwise they are not going to survive.”

These days many bookstores have space set aside for lectures and discussions. Periodically they host exhibitions and meetings with writers.

In Taiwan, Eslite hosts more than 5,000 activities a year, including exhibitions and dance performances. In Suzhou, Eslite offers more than 300 activities a year. Sometimes there are book exhibitions, such as Cai Guoqiang’s Day and Night, and Han Han’s One. Dance classes are also held there, and sometimes there are cooking demonstrations.

Anyone who hopes to deal solely in books is likely to be forced out of business by e-commerce, or other modes of doing business, says Lang.

“But if bookstore space is closely connected with consumers’ lifestyles or their hobbies, it will be rather difficult to replace.”

I missed out on a treat that took place in Suzhou the day before I arrived there, a talk by the Taiwan writer Pai Hsien-yung, but it was a delight to see the works of all my favorite woman writers on display for the International Women’s Day-Virginia Woolf, Susan Sontag, Eileen Chang, Hannah Arendt, Emily Dickinson and Yang Jiang.

At Librairie Avant-Garde trying to get an idea of the range of books available I came across a great many acquaintances, at least a couple of which I had recently finished reading, Charlotte by David Foenkinos and Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Entering Zhongshuge I found myself surrounded by a sea of books, underfoot beneath the glass floor, overhead above the glass ceiling, below the steps of the stairs, and on the walls; in short: everywhere.

The bookstore managers interviewed for this story emphasized that they are first and foremost there to sell books, although Eslite in Suzhou Industrial Park, as the developer of the land on which it stands, rents 41,000 square meters of the total 56,000 sq m to clothiers, caterers, and dealers in culturally creative products that Eslite has brought in, and it tactfully arranges related products among books with themes to match.

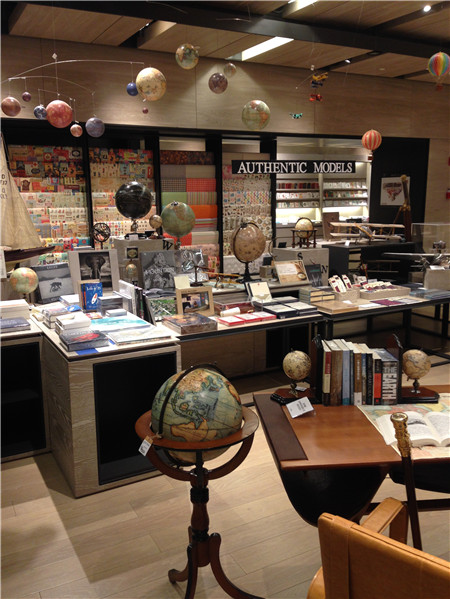

For example, near books on travel you can buy suitcases, aircraft models, world globes and book flights.

Culturally creative products are also an important money spinner for Avant-Garde, and Zhongshuge relies heavily on food and drink sales to bolster its income.

Managements of the bookstores seem to be proud about the books they sell. They do not sell textbooks and other learning aids and avoid self-help books. Avant-Garde and Zhongshuge focus on literature, arts, history and philosophy. Eslite has opened special sections on travel and lifestyle.

As someone who appreciates Vincent Van Gogh, I was happy to see at Eslite Van Gogh: Lust for Life, translated by the Taiwan writer and poet Yu Kwang-chung. The four copies of its Taiwan edition were put on the shelf among Eslite’s books of the month. Around them were The Poems of Emily Dickinson, The Illuminaries by Eleanor Catton and The Blind Massage by Bi Feiyu. Such selections, an old Eslite tradition, are organized by a team of 50 to 60 people from the mainland and Taiwan.

Avant-Garde’s Zhang Xing says that many people are now keen on opening bookstores, but in the end being able to compete with others lies in the skills and knowledge of the staff shops employ.

“We have two staff whose specific job is to choose books. They have followed the publishing industry for more than 10 years. You cannot just recruit a person with a PhD to do the job. It’s not that easy.”

Indeed, it costs a lot to run a store covering 3,750 sq m-one that was just 17 sq m when it opened 20 years ago-not to mention a store that runs at a loss year after year.

At Avant-Garde two solemn black crosses that hang overhead are unmissable, as are the 72 steps that take you to the entrance of Eslite bookstore, at the right side of which are book titles that mark the bookshop’s growth, and the star-lit ceiling of Zhongshuge’s room for art books.

All of these shops are renowned for the flair of their design and their cool ambience, which has helped turn them into must-visits for tourists.

Asked about the difference between buying books online and in physical shops, Lang equates it to the difference that a devout believer would find in praying at an online church and going to St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

“We want to change people through books. Or we just offer them a space in which the music, the smell of drinks or food, the beautiful design of the products, the touch of a good book, the names of the authors or the book titles, run to you, bringing with it knowledge, broadening your view, cultivating your tastes and in the end helping to mold your personal disposition.”

The new generation of book buyers in the mainland under the age of about 25 are different in the way they buy things, he says. Social transformation through urbanization is also bringing about new ways of buying and marketing. Looking attractive has become critical to bookstores, places where people are looking for themselves through books.

“Each Zhongshuge is different in terms of design and market niche, but they have one thing in common,” says Tao. “They are all highly attractive, and that is one of the essentials.”