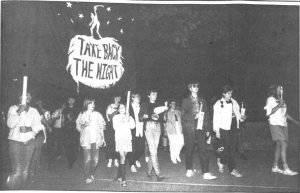

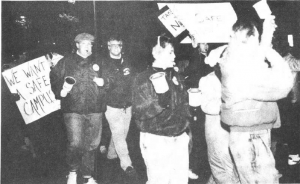

Both in 1983 and 1996 (among many other years), women of The Ohio State University and the Columbus community came together to “take back the night”. Take Back the Night is an international organization whose mission is to “end sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence, sexual abuse and all other forms of sexual violence”, through events

like the marches in 1983 and 1996 (TBTN). “Take back the night” refers to the refusal to accept the lack of sense of safety women often feel when walking in the dark, especially alone, because of the constant (subconscious or not) fear of sexual assault. Both protests invited men to participate in discussion, but they were asked to refrain from marching.

The 1983 protest consisted of about 600 women holding candles and signs and banners, marching from Central High School to a rally at the Riverfront Amphitheater. The event was sponsored by “Women Against Rape (WAR), the Federation for Progress, and it drew support from more than 20 other organizations, including the OSU Women’s Law Caucus and OSU Women’s Services” (Willke, 1983).

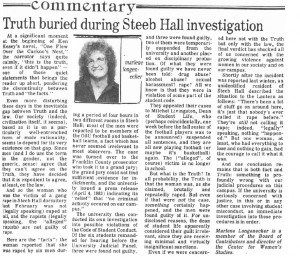

The 1996 Take Back the Night protest consisted of an estimated 300-500 women, with the Rally beginning at Sullivant Hall, proceeding with a mile long march, and ending with a candle light vigil at Sullivant Hall. The vigil displayed life size silhouettes and plaques to tell the stories of real women who had died of violence. Speakers from OSU’s Women’s Student Services, Columbus Area Rape Treatment Program, Diversity Ohio, Asian Community Outreach Program, and Columbus Women’s Chorus were among the participants of the protest.

Here are some images of Take Back the Night protests in Columbus throughout the years…

Works Cited

Hannah, Amy M., and Nichole Negulesco. “Do a Little March, Make a Little Noise, Take Back the Night.” The Lantern [Columbus] 23 May 1996: 2. Print.

“History – Take Back the Night.” Take Back the Night. Take Back the Night (TBTN), n.d. Web. 31 Oct. 2016.

Willke, Jeanne. “Women Protest Rape in Symbolic Night Rally.” The Lantern [Columbus] 16 May 1983: 1. Print.

Photos:

Fig 1 and 2: Deadhead, Daisy. Ancient Black-and-white Photos of My Hometown (Columbus, OH) Take Back the Night March (1983). 1983. Http://daisysdeadair.blogspot.com/2013/04/the-history-project-part-2.html, Columbus.

Fig. 3: Hannah, Amy M., and Nichole Negulesco. “Do a Little March, Make a Little Noise, Take Back the Night.” The Lantern [Columbus] 23 May 1996: 3.